Passover Publication!

Ever wonder why the introduction of the Passover Haggadah is in Aramaic & seems unattached to the rest of the text, & what Elijah is doing at the seder?

As I argue in a recent article, the two answers are connected!

🧵 1/32

academia.edu/44600798/Whoev…

Ever wonder why the introduction of the Passover Haggadah is in Aramaic & seems unattached to the rest of the text, & what Elijah is doing at the seder?

As I argue in a recent article, the two answers are connected!

🧵 1/32

academia.edu/44600798/Whoev…

The P Haggadah is almost entirely in Hebrew, and primarily consists of citations of scripture, rabbinic literature, liturgy, & poetry. Yet it begins with an Aramaic intro with no clear basis in any preceding Jewish text, confusing practitioners & scholars for centuries. It reads:

This is the bread of affliction that our parents ate in the land of Egypt. Whoever is hungry, let him come & eat; whoever is in need, let him come & perform the Passover. This year we are here, next year.. in the land of Israel. This year we are slaves, next year we will be free.

Though there are extensive discussions of what one should recite on Passover in rabbinic literature, this opening formula doesn't appear anywhere. We do have a description of its practice by the academy head Rav Matityah (d. 869 CE). He explains:

This was our ancestors' custom, they would..not close their doors. Their neighbors were Jews. They would recite this [intro] to receive reward. Now that our neighbors are gentiles, we support [Jews] earlier so they do not go begging, & then we...recite, like the earlier custom.

Rav Matityah first notes that the recitation of the invitation was accompanied by a practice to open the door. The formula & practice were an ancestral custom. Jews would leave their doors open & recite the invitation in order to invite poor Jewish neighbours to join them.

Due to changing demographics, his practice transitioned from a social custom to a formalised ritual. As a result, the custom was changed so that indigent Jews were funded before the Seder, to prevent them from begging &, presumably, from excessively interacting with non-Jews

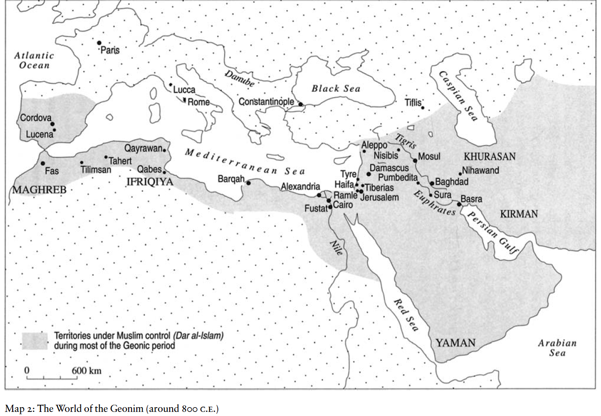

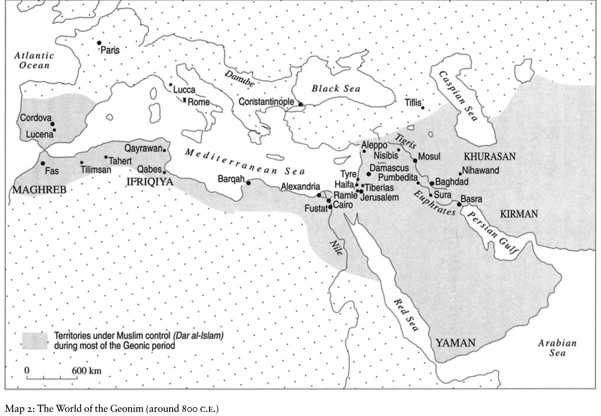

By the 9th C in Iraq there was a custom to recite the invitation and open the door at the outset of the Haggadah. This practice was, however, already undergoing change. Yet, precisely when this practice originated and entered the Haggadah remains uncertain.

Particularly, when Rav Matityah refers to the “custom of our fathers,” is he referring to his immediate ancestors, or to ancestors in the distant Jewish past?

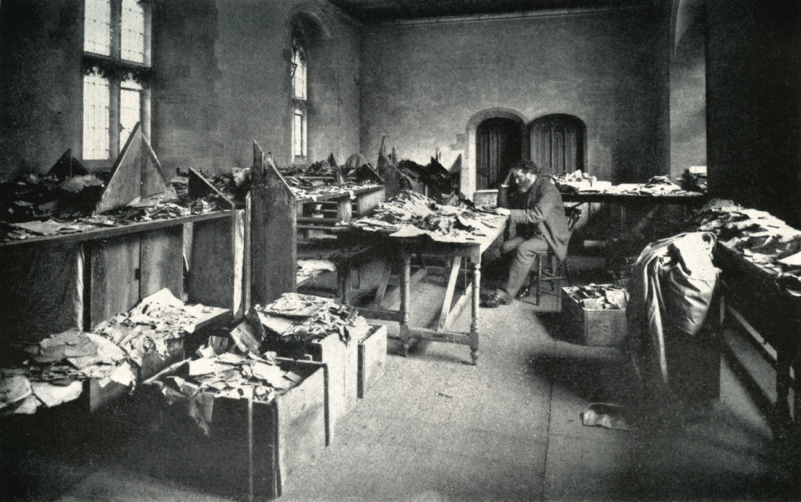

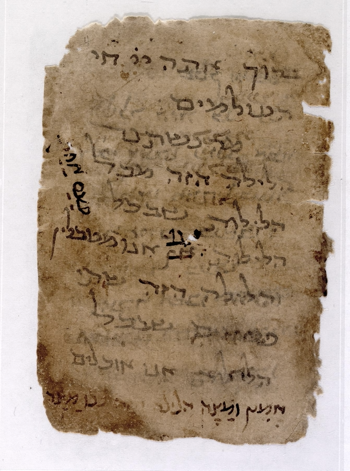

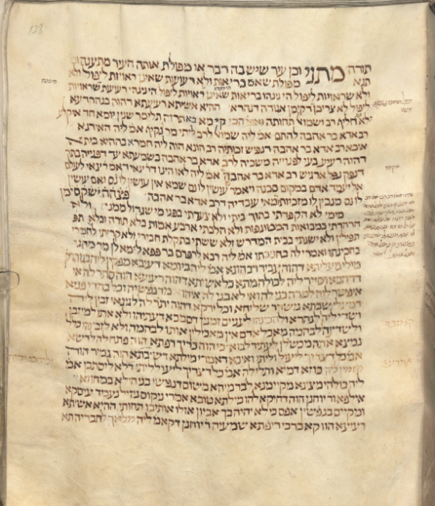

A solution to the origins of this practice came from the Cairo Genizah. An early medieval manuscript discovered there (Halper 211), now in the @katzcenterupenn, preserves a different version of the Haggadah than what would become the standard version across the Jewish world.

As these scholars argued, Halper 211 represented the Haggadah according to the early Medieval Palestinian tradition, rather than Babylonian. One of the noteworthy features that distinguishes these Palestinian Haggadahs from the Babylonian is the absence of the opening invitation!

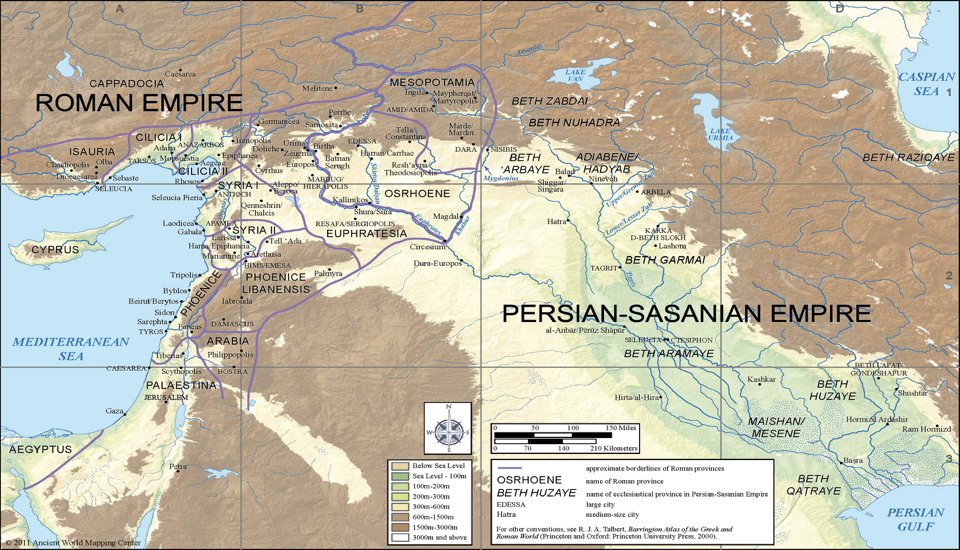

When Rav Matityah said that the custom to open one’s door & recite the invitation dates to his ancestors, he appears to have meant his local Babylonian ancestors in the recent rather than distant past. The passage's origin is therefore to be found in late antique Jewish Babylonia

And in fact, earlier Babylonian Jewish texts contain several close parallels to the invitation formula. 2 such parallels are found in the Babylonian Talmud. Both stories extoll the virtuous deeds of wealthy rabbis, & are entirely unrelated to Passover or Jewish festivals.

In one, rabbis report that “When [Rav Huna] would eat a meal, he would open the door (דשא) & say: ‘Whoever is in need, come and take.’” Others added: “When [Rav Huna] learned of a medical remedy, he would draw a pitcher, hang it up, & say: ‘whoever is in need, come & take...’

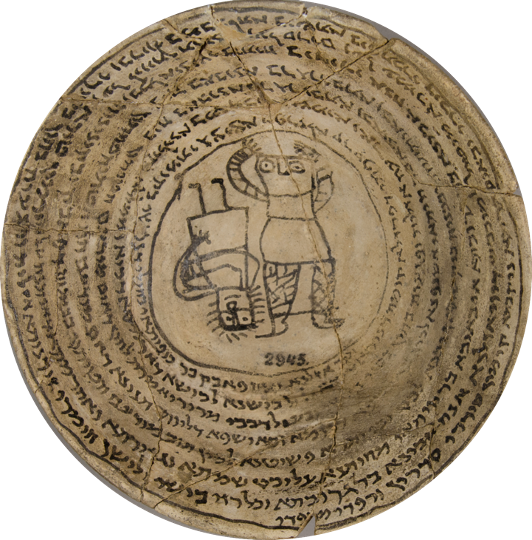

Alongside the two stories in the Babylonian Talmud, the invitation formula is also attested among the fascinating Aramaic Incantation bowls. In several Jewish Babylonian incantation bowls, malevolent forces marshal at the doors (בבין) of the house of those seeking protection.

In response, those seeking protection climb to the roof of the house & issue an invitation to the evil forces at their door, offering for them to partake of goods or to depart: “If you are hungry, come & eat! If you are thirsty, come & drink! If you are dry, come & be anointed!”

The invitation appears to disarm the malevolent forces by setting the terms of their entry into the house apart from which they must leave. This invitation is publicized from the rooftop, meant to grab the attention of those forces around the doors of the home.

Each of these sources attests the a priori & independent existence of the invitation, intended for the haves to provide for the have-nots. Each of the sources attest a recognized social script with a similar formulaic invitation & physical welcome for guests to partake.

If the invitation & open door in the Passover Haggadah is an iteration of a local Babylonian Jewish social script, how & why did a custom develop to include this invitation in the Haggadah in the first place?

I suggest that the core theme of the Passover Haggadah, the obligation for participants to playact the transition of the ancient Israelites in their Exodus from Egypt from slavery to freedom, from poverty to wealth, was expressed by Babylonian Jews through a local social script.

As Rav Matitya notes, as demographic conditions shifted, & Jews were outnumbered locally, the previous practice was no longer tenable. Support for the poor was transformed from an ad hoc personal invitation to an institutionalized practice of communal charity before Passover.

Despite these momentous demographic changes, Rav Matityah informs us that he & his followers did not jettison the custom entirely. An invitation meant to reach the poor was, instead, preserved as a ritual and textual act, an utterance recited by & for the meal participants alone.

At around this moment, Babylonian Jewish traditions, including the Haggadah, spread across the Jewish world. Without communal memory of the Babylonian Jewish social milieu in which it arose, new communities struggled to understand why the opening invitation was in the Haggadah!

An early anonymous and influential commentary on the Haggadah exclaims bewilderedly about the invitation: ‘and does every man open their entrance and declare ‘whoever is hungry come and eat with me’?’ In early medieval Iraq, of course, the answer was yes!

Jews also preserved the practice to open the door, yet began offering new interpretations for it. The North African rabbi Nissim b. Yaaqov (d. 1057) reports that on Passover evening "the doors of the house remain open..so that when Elijah comes we will.. greet him speedily..”

Nissim b. Yaaqov is the earliest evidence that the practice to open one’s door was disaggregated from the invitation and treated as a distinct ritual act, receiving an entirely new etiology as a sign of faith in god’s promise of salvation.

26

26

Given that the open door was now associated with the anticipation of the arrival of the Messiah, some traditions relocated the open door to the end of the Seder, near the fourth and final ritual cup of wine, which already was thought to symbolize the final stage of salvation.

At this point in the meal, some communities beginning in 11th century added a prayer for the speedy destruction of Israel’s enemies (‘Pour out Your Wrath on the nations’). These two practices signifying salvation – the open doors & the prayer during the final cup – merged.

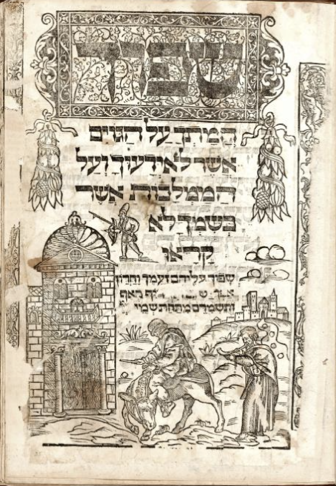

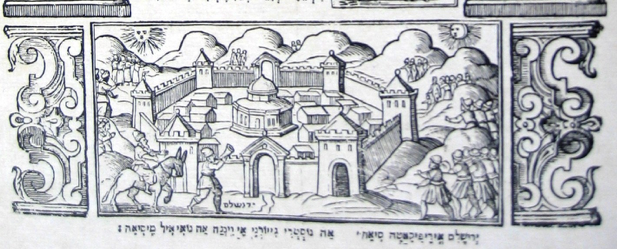

Whereas in the earliest illustrated Haggadot from the 13/14th c. lack depictions of Elijah and the Messiah, by the 15th c., German and related illustrated Haggadot begin to depict either the Messiah alone or with Elijah, at the 4th cup of the meal.

In the 16th c, some dressed up as Elijah entering through the open door, mimicking his much anticipated arrival. Others even suggested that the meal participants should issue an invitation to Elijah and the Messiah from the open door, which reads: ‘Elijah and the Messiah, enter!’

Lastly, as the association between the open door, Elijah’s arrival, and the fourth and final cup was solidified, one other practice emerged, known as the cup of Elijah. First attested in the fifteenth century in illuminated Haggadot, it is still practiced to this day.

As the custom drifted further from its original social context, it regained some of its initial purpose! However, instead of inviting the poor, this tradition invited Elijah the prophet to enter, and even to partake of wine.

The Haggadah is a paradigm of the way traditions are in a continual process of formation & development as they travel across time and space, encountering new actors and cultural milieus.

Hag Sameah to all who celebrate!

Fin.

Hag Sameah to all who celebrate!

Fin.

For those who are interested in reading more, the article is available here! academia.edu/44600798/Whoev…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh