Do you want a thread exploring the links between:

*that ship stuck in Suez

*the Trojan War

*the founding of Singapore

*and Chinese foreign policy, from the Belt and Road and South China Sea to Taiwan?

Of course you do!

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

*that ship stuck in Suez

*the Trojan War

*the founding of Singapore

*and Chinese foreign policy, from the Belt and Road and South China Sea to Taiwan?

Of course you do!

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

The Ever Given getting stuck while traversing the Suez Canal is playing out as a sort of slapstick routine.

But it underlines a serious point that's in many ways the axis on which modern geopolitical tensions turn.

If you can control ocean straits, you can control the world.

But it underlines a serious point that's in many ways the axis on which modern geopolitical tensions turn.

If you can control ocean straits, you can control the world.

That's been the case since ancient times.

We don't know that much about what caused the Trojan War or whether it even happened, but there's lots of evidence that historical Troy was a trading centre of huge importance to ancient Greek states:

We don't know that much about what caused the Trojan War or whether it even happened, but there's lots of evidence that historical Troy was a trading centre of huge importance to ancient Greek states:

That's because it can control a crucial ocean strait, the Dardanelles.

At its narrowest point at Canakkale the Dardanelles are just 1.5km wide, and ocean swimmers regularly hold events crossing it.

At its narrowest point at Canakkale the Dardanelles are just 1.5km wide, and ocean swimmers regularly hold events crossing it.

The Bosphorus in Istanbul is even narrower.

Greece's denuded soils left it dependent on grain imports from the Black Sea from quite early times, so control of these straits was an existential issue.

Greece's denuded soils left it dependent on grain imports from the Black Sea from quite early times, so control of these straits was an existential issue.

The origins of the (real and historical) Greco-Persian wars came with a tussle over control of the culturally Greek Ionian city-states along the Turkish coast and up to the Dardanelles.

This pattern repeats through history. India's Kerala and Tamil Nadu coasts dominated east-west trade from antiquity because they dominated another sort of strait -- the monsoon trade winds that could get sailing ships from the Red Sea to Southeast Asia.

The British Empire were the real experts in this business. Look at a map of the world's crucial ocean straits and it's truly astonishing how much of it was controlled by the British, from Gibraltar ...

... to the Gulf of St Lawrence, giving access to the Great Lakes and the interior of North America (note the French nipping at Britain's heels with St Pierre & Miquelon) ...

... to Central America, where despite only getting control of one big island (Jamaica) the British controlled all but a handful of the small islands from the Bahamas to Trinidad that controlled access to the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico:

The direct route on the trade winds from Africa takes you right between the British colonies of Montserrat and Dominica, where right in the middle you find Guadeloupe, controlled by -- surprise, surprise -- France.

The Straits of Hormuz, through which a third of the world's seaborne oil now passes, was dominated by British-aligned Gulf emirates and the Omani sultanate:

And then you have the Red Sea, where the British and French contended over control of Egypt and had colonies at Aden and Djibouti on either side of the Bab el-Mandeb:

In the 19th century they had a problem in Southeast Asia, where the Dutch in Batavia (modern-day Jakarta) controlled the straits between the islands of Indonesia and charged hefty taxes on British shipping travelling between China and India.

So Stamford Raffles starts scouting out locations for a trading post and hits on an island with about 150 inhabitants at the end of the Malaysian peninsula that the Dutch and the Sultan of Johor aren't really interested in: Singapore.

It's tempting to think that in the modern world, with the rise of aviation, telecommunications, and global finance, maritime straits don't matter all that much.

I'd argue that it's close to the opposite. They matter now more than they ever did in the past.

I'd argue that it's close to the opposite. They matter now more than they ever did in the past.

For one thing, we're much more dependent on the constant and uninterrupted flow of goods round the world.

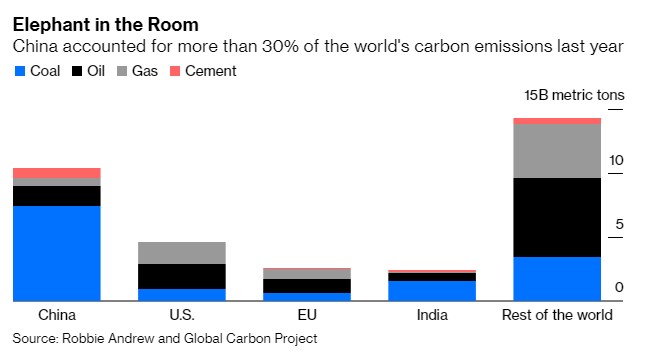

Two-thirds of the world's crude moves by sea. Oil demand may have peaked but right now, if you stopped that flow, economies will grind to a halt quite quickly.

Two-thirds of the world's crude moves by sea. Oil demand may have peaked but right now, if you stopped that flow, economies will grind to a halt quite quickly.

The same goes for food. Only about 30 or 40 countries out of 195 in the world are self-sufficient in terms of calories. Cut off the supply of grain to the other nations and you can bring them to their knees rather quickly.

The same rule applies for other commodities, too, as well as for exports -- which most countries are going to need if they want to pay for those imported goods.

The other thing that's changed is the growth of aircraft carriers and long-range artillery. In the Age of Sail it was quite difficult to threaten an enemy ship in the ocean because it was hard to catch up with it.

The age of Gunboat Diplomacy and really being able to using warships as a maritime threat begins in the era of steamships, and accelerates with the invention of aircraft carriers that can interdict shipping within a several hundred-nautical mile radius.

A single aircraft carrier is quite sufficient to block any one of the world's major ocean straits, the widest of which are less than 100 nautical miles across.

That's where Chinese foreign policy comes in. Because of the way the Pacific and Asian tectonic plates crash into each other, there's a fence-like string of volcanic islands along the edge of east Asia.

Without touching the Asian mainland, you can make it all the way from Alaska down to Australia without crossing more than 100 nautical miles of open ocean.

It's not hard to see why China -- which depends on seaborne imports for about three-quarters of its oil and iron ore, not to mention animal feed and foreign exchange from its export trade -- is worried about that.

A U.S.-supported alliance between Japan, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Indonesia -- which isn't likely right now, but isn't something a military planner would want to rule out -- could completely cut off China from the world's oceans.

A lot of the biggest Belt and Road infrastructure projects look like an attempt to bypass the Straits of Malacca and Singapore, from an oil pipeline through Myanmar and a railway across Malaysia to the China-Pakistan economic corridor and subsidies for trans-Asian rail.

Similarly, the tensions over the South China Sea make most sense when you consider that the disputed islands and innavigable shoals like the Spratly and Paracel Islands in effect split the sea into a series of ocean straits:

And, finally, it's worth thinking about Taiwan. While the motivation for making threatening noises about invasion is clearly nationalistic, it's worth reflecting how much Taiwan controls China's gateways to the world, and even to parts of its own territory.

Taiwan has territory on both sides of the Taiwan Strait, including heavily-fortified islands just a stone's throw from the Chinese port of Xiamen.

Southeastern China is difficult, hilly country and to this day a huge amount of cargo between Shanghai and Guangdong goes by sea.

Southeastern China is difficult, hilly country and to this day a huge amount of cargo between Shanghai and Guangdong goes by sea.

Similarly, the straits linking the Taiwanese mainland with outlying islands of Japan and the Philippines are only about 50 nautical miles wide.

As some people have pointed out in replying to this thread, China is also one of the key backers of proposed new ocean canals across Thailand's Isthmus of Kra and Nicaragua, which could help bypass Singapore and U.S.-dominated Panama.

I'm not smart enough to offer any solutions, but I think it's important to recognize how threatening the configuration of these ocean straits appears if you're sat in Beijing.

China's moves around the South China Sea and Taiwan come across as militarily offensive, but there's a very fundamental defensive aspect to them too. If we're going to seek a diplomatic solution to these tensions, we need to recognize that and accommodate it.

The freedom of the open oceans has been guaranteed for centuries by the Pax Anglica and Pax Americana, which has worked very well if you're Britain or America or one of their allies.

That freedom has been hugely beneficial to the world, but it's rarely had to cope with a world where a rising power with the capability to project naval power is not exactly an ally of either Britain or America.

The world is going to have to manage this better than it did that time around, and this Suez mishap should be a reminder of how important it will be to get that right.

Read the column here: (ends)

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

Read the column here: (ends)

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

A couple of postscripts:

It's often pointed out by historians that Vasco da Gama's 1497 voyage from Portugal to India was one of history's great anticlimaxes.

It's often pointed out by historians that Vasco da Gama's 1497 voyage from Portugal to India was one of history's great anticlimaxes.

If you look at the price of Asian luxury goods in Europe, opening up this new backdoor trade route appears to have made no difference at all.

Spices and fabric didn't cost any less than they did when Venetian-Ottoman traders monopolized commerce.

Spices and fabric didn't cost any less than they did when Venetian-Ottoman traders monopolized commerce.

I think there's two problems with this.

One is that nominal prices aren't a good guide to what was happening in the early 16th century, because at the same time Columbus had opened up the Atlantic and gold and silver were flooding from the Americas into Europe.

One is that nominal prices aren't a good guide to what was happening in the early 16th century, because at the same time Columbus had opened up the Atlantic and gold and silver were flooding from the Americas into Europe.

So what looks like zero price change in nominal terms is actually significant *deflation* in real terms, when you consider the rapid devaluation of European currencies that was happening at the same time.

The other factor is that Vasco da Gama's route — crawling up the east coast of Africa before joining the monsoon route around Mombasa — wasn't a huge improvement in terms of speed compared to the traditional route.

And as any shipper knows, time is money.

And as any shipper knows, time is money.

The real game-changer came a century later, when Dutch navigator Hendrik Brouwer made the seemingly insane decision to head due south from Africa towards Antarctica.

This allowed him to catch the Roaring Forty winds that whip around the globe almost uninterrupted by land, making a much quicker passage to Southeast Asia that cut out India altogether.

It's Brouwer, rather than da Gama, who really transformed east-west trade.

It's Brouwer, rather than da Gama, who really transformed east-west trade.

Second postscript:

It's no accident that the 1956 Suez Crisis, where Britain and France tried to take control of the canal and had to withdraw when the U.S. refused to offer support, is seen as the humiliating end of their empires and a key moment in the rise of U.S. hegemony.

It's no accident that the 1956 Suez Crisis, where Britain and France tried to take control of the canal and had to withdraw when the U.S. refused to offer support, is seen as the humiliating end of their empires and a key moment in the rise of U.S. hegemony.

Fail to control the ocean straits, and you fail to control the world.

Last point: The one other type of global commerce that really is independent of ocean straits is the international flow of funds — but here U.S. hegemony is even greater than it is on the seas.

If you or any of your trading partners want to do any business with anyone who uses dollars, your money must (metaphorically) sail through a narrow, easily-controlled strait called the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.

If you violate U.S. sanctions anywhere in the world, regardless of laws in your own country, you may find yourself like BNP Paribas, on the sticky end of an $8.9 billion dollar fine: reuters.com/article/us-bnp…

Or like Hong Kong governor Carrie Lam, whose apartment is filling up with cash because even Chinese-owned banks in Hong Kong won't handle her money in violation of U.S. sanctions: abc.net.au/news/2020-11-3…

(ends, really)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh