“Mobilization” is not just about increasing the size of the Army. In the context of this series, it is the process of reallocating “a nation’s resources for the assembly, preparation, and equipping of forces for war.”

In the mid-1800s, the United States Army faced circumstances that forced it to change the way we prepare for war.

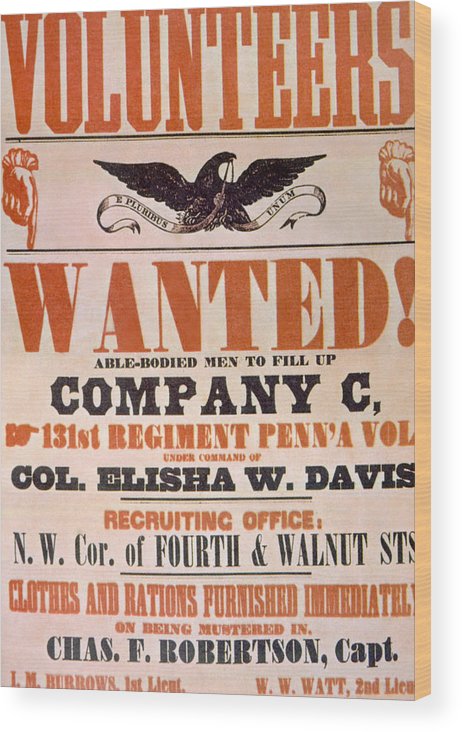

Recruiting wasn’t bringing in sufficient numbers of volunteers so the government enacted conscription – a draft.

Both sides in the US Civil War used conscription to fill their ranks. They also pushed the concepts of “national military obligation” and the need to gather productive resources to sustain the military.

Actually, if we want to be technical about it, there was also conscription for the Revolutionary War. So, World War II would see the 4th Draft in US history.

With the rise of industrial power after the Civil War, the US began looking outward, beyond our borders, with regard to our national interests. Resources are finite and industry depends on them.

Until 1903, the highest-ranking officer in the US Army was the Commanding General of the US Army and he reported to the US Secretary of War.

(We used to have a War Department before we had the Department of Defense. One sounds a bit cooler, but we rebranded.)

(We used to have a War Department before we had the Department of Defense. One sounds a bit cooler, but we rebranded.)

In 1903 things changed. The Army got a General Staff and an Army Chief of Staff. The first Chief of Staff was Lieutenant General Samuel B. M. Young. We’re not going to talk about him.

The second Chief of Staff was Lieutenant General Adna Chaffee. We’re not going to talk about him either.

But we will talk later about his son, Adna R. Chaffee, Jr. #TankTwitter

This new General Staff was given the important mission of planning for mobilization and national defense. And this ushered in significant changes to the Army overall.

Broader concepts than simply “fight wars” began reshaping the Army’s purpose. And these changes were reflected in Army regulations, training and exercises, force structure, and more.

In April of 1917, the United States entered World War I in support of the Allies. We weren’t ready. It would not be an exaggeration to say the US Army in 1917 had no idea what they were getting it.

We did not have stockpiles of weapons and equipment for soldiers to take to war. And there were no plans to create stockpiles of equipment for soldiers to take to war. Even if there were plans, we didn’t really know what to produce or how much. This was new territory.

And this situation – being unprepared for war before entering one – forced the United States Army to improvise and compensate.

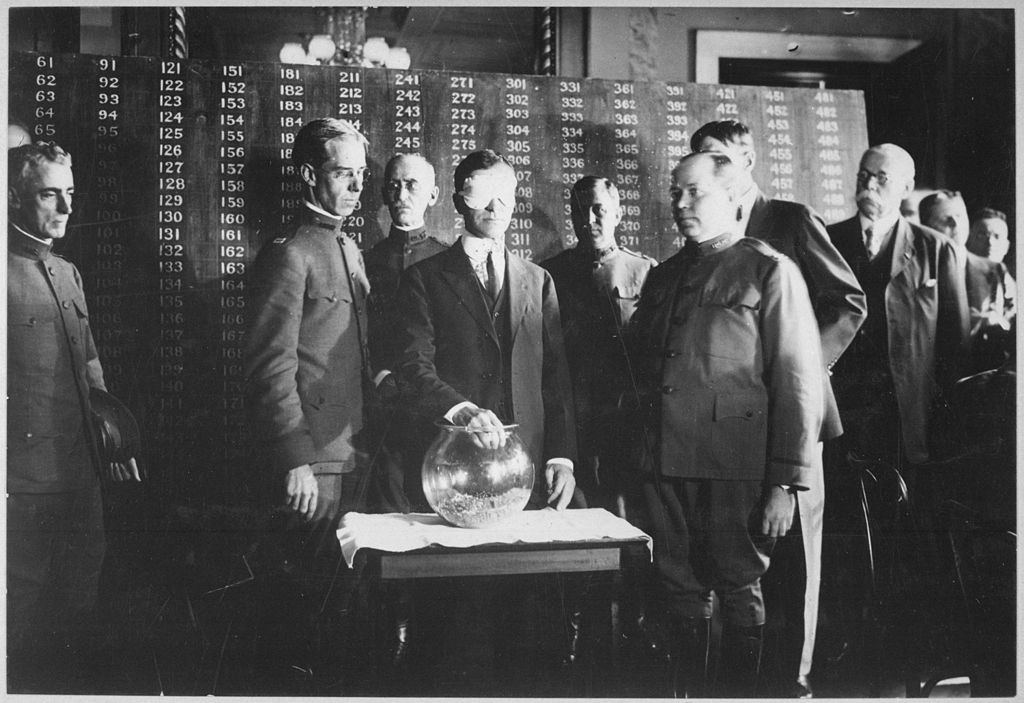

In May 1917, President Woodrow Wilson approved the Selective Service System, which would become the basis for conscription in the United States for future decades.

The problem in 1917 was that the Army didn’t have the “business” experience needed to effectively plan and produce equipment, supplies, and facilities. It is one thing to mass an army – another thing entirely to supply and sustain it.

The old school supply system was comprised of independent, decentralized elements that were more focused on things that benefit them than on supplying the military, and certainly not on a large enough scale to fight a war.

There was also competition for resources between the @USArmy and @USNavy, and with that competition there came increased costs of materials and production.

President Wilson’s solution for this was to establish the War Industries Board in July 1917, and to task this Board with coordinating Army and Navy purchasing and establishing purchasing priorities.

In order to determine the priorities for resources, supplies, and transportation, the Army and Navy both had to submit requests with their lists of needs.

Interestingly, neither the Army nor Navy wanted to leave it up to the Board, so they started deciding priorities between themselves before submitting requests for purchasing, storage, or traffic. This greatly minimized issues in the process.

At the end of WWI, the US Army had a very large surplus of equipment and more than 3.5-million soldiers. So, when faced with the need to expand the military and produce equipment and supplies to arm and sustain a massive force, we proved we could.

James Huston, a historian specializing in logistics, has said that in WWI the US “revealed the greatest war-making capacity the world had ever seen.”

That’s all well and good, but it doesn’t mean anything if we don’t take the lessons learned and apply them to future circumstances. @USArmy_CALL knows what we’re talking about😉

It was extremely time-consuming and costly to mobilize industry and produce the materiel needed to fight in WWI.

And as Benedict Crowell, the Assistant Secretary of War during WWI, said: the war “upset the previous opinion that adequate military preparedness is largely a question of trained manpower.”

If you're just tuning in or you've missed any of the previous threads, you can find them all saved on this account under ⚡️Moments or with this direct link twitter.com/i/events/13642…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh