Why do participants at the Passover Seder dip & remove 16 drops of wine when mentioning the plagues in Egypt?

The earliest explanations (c. 13th c.) make clear this is a kind of sympathetic magic: "[This custom] teaches us that we will not be injured [by the plagues]."

🧵

1/4

The earliest explanations (c. 13th c.) make clear this is a kind of sympathetic magic: "[This custom] teaches us that we will not be injured [by the plagues]."

🧵

1/4

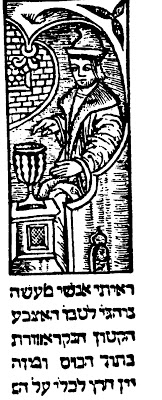

The caption under the woodcut in Prague Haggadah 1526, depicted above, says this quite clearly:

“It seems to me that it is a hint [that] ‘All of the illness which I put on Egypt, I will not put on you’ (Exodus 15:26).” In other words, “as if to say, they should not harm us”.

“It seems to me that it is a hint [that] ‘All of the illness which I put on Egypt, I will not put on you’ (Exodus 15:26).” In other words, “as if to say, they should not harm us”.

Others would reinterpret the custom to refer both to Jews being saved from plagues, & also as a call to bring the plagues upon their enemies.

Shalom of Neustadt (d. c. 1413): "we should be saved from these plagues & may they come upon the heads [of the nations of the world]."

Shalom of Neustadt (d. c. 1413): "we should be saved from these plagues & may they come upon the heads [of the nations of the world]."

Both of these explanations would grow out of favor, largely replaced by a more amicable one: it symbolizes the diminished joy Jews (should) experience at the suffering of others.

Another example for how the Haggadah has been reinterpreted over time and in new contexts.

Fin.

Another example for how the Haggadah has been reinterpreted over time and in new contexts.

Fin.

For various explanations, see here: schechter.edu/why-do-we-spil…. For the increasing popularity of the "diminished joy" explanation, see here: hakirah.org/Vol19Ron.pdf.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh