This just got published and is very good.

A new study that asks: How has extreme poverty changed in the last 2 centuries?

The authors estimate poverty in many ways.

Their main innovation is to rely on 'a cost of basic needs approach' based on Bob Allen’s recent work.

👇 thread

A new study that asks: How has extreme poverty changed in the last 2 centuries?

The authors estimate poverty in many ways.

Their main innovation is to rely on 'a cost of basic needs approach' based on Bob Allen’s recent work.

👇 thread

The authors write that in 1820 roughly three-quarters of the world "could not afford a tiny space to live, food that would not induce malnutrition, and some minimum heating capacity.”

As you see in the chart above, the huge majority of the world was extremely poor in the past.

As you see in the chart above, the huge majority of the world was extremely poor in the past.

Since 1820 the share in extreme poverty across the globe declined to 10%, "the lowest level ever achieved", according to this study.

But of course more recently the share in extreme poverty has unfortunately increased.

But of course more recently the share in extreme poverty has unfortunately increased.

https://twitter.com/maxcroser/status/1314669368450723841

Just as in this @OurWorldInData chart the authors of the new study find that the *number* of extremely poor people increased steadily until about 30 years ago.

Since then the number of people living in extreme poverty declined.

Since then the number of people living in extreme poverty declined.

But of course with *very* large differences across world regions.

This is something that has not been done before (to the best of my knowledge): a breakdown of the share in extreme poverty across world regions over the last two centuries.

This is something that has not been done before (to the best of my knowledge): a breakdown of the share in extreme poverty across world regions over the last two centuries.

The new report is here oecd.org/publications/h…

It is very interesting more broadly. I’m happy to see that the authors rely on our @OurWorldInData work – with @EOrtizOspina – on the history of the welfare state and quote our historical numbers.

It is very interesting more broadly. I’m happy to see that the authors rely on our @OurWorldInData work – with @EOrtizOspina – on the history of the welfare state and quote our historical numbers.

For me it’s in some ways bad, because we just submitted a paper in which we also study the history of global poverty…

But while it reduces the uniqueness of our forthcoming paper, I’m very happy to see how close our poverty estimates are to this study.

But while it reduces the uniqueness of our forthcoming paper, I’m very happy to see how close our poverty estimates are to this study.

And one thing we do in our forthcoming paper (currently under peer-review) which is not done here is to look at higher poverty lines – not just 'extreme poverty', but also $5, $10, and higher poverty lines.

What's striking in this paper is how close the various estimates for poverty in the past are.

That's striking because there is a large uncertainty around these estimates, but also because a large share of the world was living just below, or just above this basic needs threshold.

That's striking because there is a large uncertainty around these estimates, but also because a large share of the world was living just below, or just above this basic needs threshold.

And it's great to see this because it was my old 'boss' Tony Atkinson who recommended to use such a cost of basic needs method as an alternative (or complementary) method in monitoring poverty.

As I said, the authors also study extreme poverty by world region, this is the history of Europe.

A large share there was very extremely poor two centuries ago. As it was the first region to achieve strong growth poverty then declined and after a rise around WWII got close to 0.

A large share there was very extremely poor two centuries ago. As it was the first region to achieve strong growth poverty then declined and after a rise around WWII got close to 0.

These are the estimates for Latin America and the Caribbean.

A high share of people remained in extreme poverty for much of the 19th century. Much later than in Europe did poverty start to decline and a significant share is still very poor.

A high share of people remained in extreme poverty for much of the 19th century. Much later than in Europe did poverty start to decline and a significant share is still very poor.

The history of poverty in South and Southeast Asia – dominated poplation-wise by India – is again very different:

• A high share of poverty during the colonial period – and rising in the first half of the twentieth century.

• And a rapid decline in poverty since independence.

• A high share of poverty during the colonial period – and rising in the first half of the twentieth century.

• And a rapid decline in poverty since independence.

I've just written about how colonial rule kept large shares of the world in poverty and why the end of colonial oppression is one reason to hope that countries where people are still extremely poor today can leave poverty behind in the years ahead.

(here ourworldindata.org/poverty-minimu…)

(here ourworldindata.org/poverty-minimu…)

The study is mostly focused on getting the data right and explaining the methodology.

One thing that I think is good is that they give some indication of the quality of the data, even if such an assessment is necessarily always somewhat subjective.

One thing that I think is good is that they give some indication of the quality of the data, even if such an assessment is necessarily always somewhat subjective.

What the study is less focusing on is the question of how this extremely large decline of poverty was possible.

The cited Bob Allen is one of the great experts on this big question if you are looking for research on this.

For example read: amazon.com/Industrial-Rev…

Or for a very short one amazon.de/-/en/Robert-C-…

For example read: amazon.com/Industrial-Rev…

Or for a very short one amazon.de/-/en/Robert-C-…

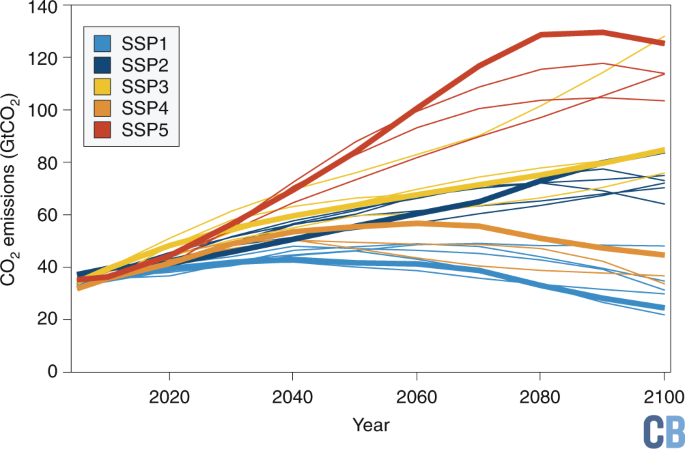

What the study does include is this plot of the correlation between poverty and GDP per capita over time.

Of course these measures are highly correlated – where average incomes are high, poverty is low.

But not perfectly, because the distribution of incomes matters too.

Of course these measures are highly correlated – where average incomes are high, poverty is low.

But not perfectly, because the distribution of incomes matters too.

Anyways, I'll leave it at that.

If you are interested in the history of extreme poverty, we wrote this article about it two years ago: ourworldindata.org/extreme-histor…

And soon we'll publish our new paper that I mentioned above.

If you are interested in the history of extreme poverty, we wrote this article about it two years ago: ourworldindata.org/extreme-histor…

And soon we'll publish our new paper that I mentioned above.

If you actually read this far into this thread then you are probably really intersted in poverty!

Perhaps you find these recent one of mine useful:

– What should our ambitions for the future of poverty be? ourworldindata.org/higher-poverty…

– How can we get there?

ourworldindata.org/poverty-minimu…

Perhaps you find these recent one of mine useful:

– What should our ambitions for the future of poverty be? ourworldindata.org/higher-poverty…

– How can we get there?

ourworldindata.org/poverty-minimu…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh