Very excited to share a new NBER working paper that I collaborated on, with Mark Shepard and @econmyles: nber.org/papers/w28630

We evaluate a policy Massachusetts had in place prior to the ACA, which we call "automatic retention."

This is a policy design we should revisit. /1

We evaluate a policy Massachusetts had in place prior to the ACA, which we call "automatic retention."

This is a policy design we should revisit. /1

Some quick programming notes:

-This is forthcoming next month in AEA Papers and Proceedings

-Here's a link without a paywall: scholar.harvard.edu/files/mshepard…

-Some figures I'm pulling from Mark's AEA presentation, rather than the WP itself

/2

-This is forthcoming next month in AEA Papers and Proceedings

-Here's a link without a paywall: scholar.harvard.edu/files/mshepard…

-Some figures I'm pulling from Mark's AEA presentation, rather than the WP itself

/2

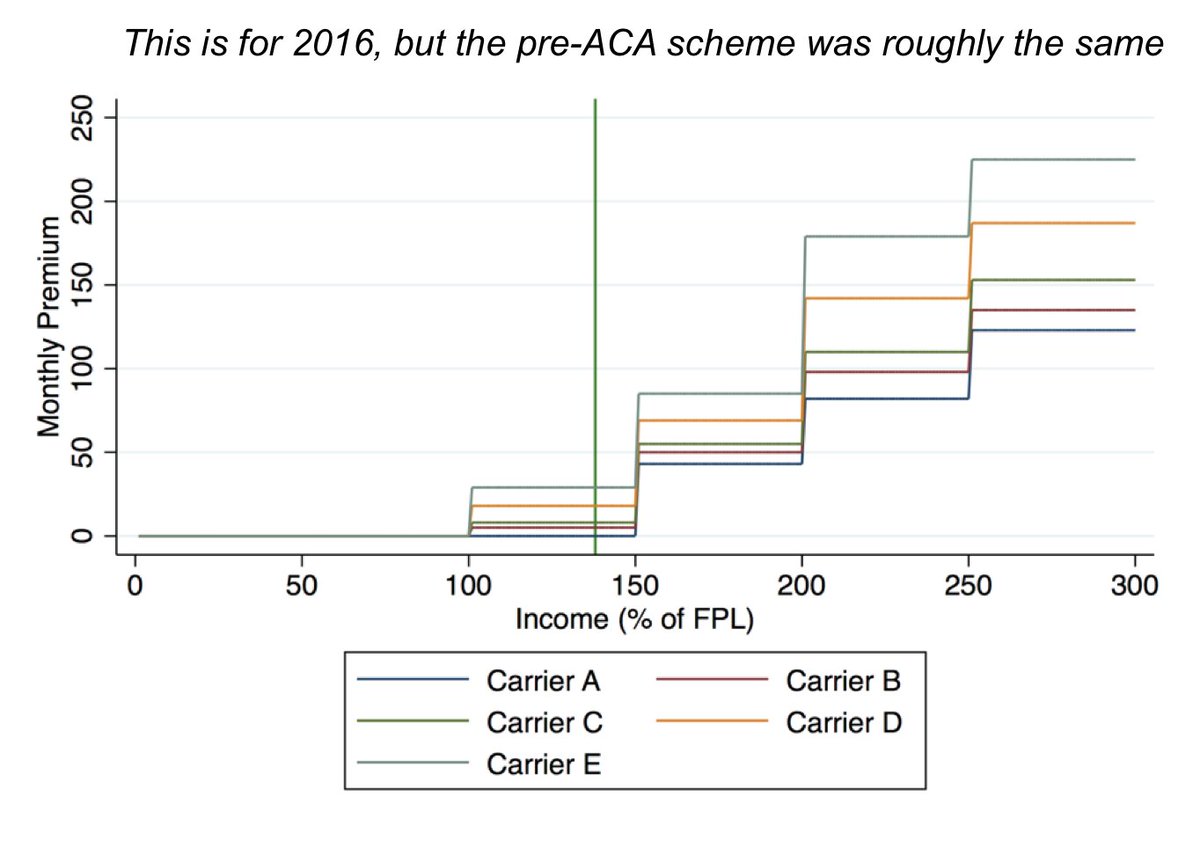

First, some background: Prior to the ACA, Massachusetts had an exchange (CommCare) that looks very similar to present-day ACA marketplaces for households < 300% FPL.

Plan choices were more standardized, though, and people had a limited choice set, a maximum of 5 products. /3

Plan choices were more standardized, though, and people had a limited choice set, a maximum of 5 products. /3

And rather than a linear subsidy scheme, CommCare's subsidy scheme was tiered or stepwise. (See figure.)

- For people < 100% FPL, all plans were zero-premium ($0)

- For people 100-150% FPL, *only* the cheapest plan was always $0

-For people over 150% FPL, no plans were $0

/4

- For people < 100% FPL, all plans were zero-premium ($0)

- For people 100-150% FPL, *only* the cheapest plan was always $0

-For people over 150% FPL, no plans were $0

/4

We focus on that 100-150% FPL group. Why? Because the plan that is zero-premium isn't always stable year-over-year (competition at work).

We saw changes in the carrier offering the zero-premium plan for most rating areas in three of the four years we examined (2010-2013). /5

We saw changes in the carrier offering the zero-premium plan for most rating areas in three of the four years we examined (2010-2013). /5

For our that group, positive-premium plans ranged from $2 to $34 dollars and were on average about $9 (weighted for enrollment).

In this paper, we ask what happens when people stay in the same plan, but transition from owing $0 per month to owing that $2-to-$34 per month. /6

In this paper, we ask what happens when people stay in the same plan, but transition from owing $0 per month to owing that $2-to-$34 per month. /6

As a reminder, everyone receives notices and is permitted to switch into the new $0 plan during open enrollment.

But we know that inertia is a huge problem—that people are exceedingly "sticky" in their plan choices. /7

But we know that inertia is a huge problem—that people are exceedingly "sticky" in their plan choices. /7

https://twitter.com/bjdickmayhew/status/1379066984982310914

Under current law, if people don't switch and lapse on premiums, they're termed for nonpayment (after a 3-month grace period).

But before the ACA, Massachusetts had a "smart default:" instead of terminating people after lapsing, they auto-switched them into the newly-$0 plan. /8

But before the ACA, Massachusetts had a "smart default:" instead of terminating people after lapsing, they auto-switched them into the newly-$0 plan. /8

People had the opportunity to switch but didn't—maybe they didn't understand or know how. Administrative burdens!

This policy is built on a premise that people would rather be switched to a new carrier (with a new network) than lose coverage altogether. /9

This policy is built on a premise that people would rather be switched to a new carrier (with a new network) than lose coverage altogether. /9

Can we tell if it worked? Unfortunately we don't have *explicit* flags for these auto-switches.

But we do know they'd be concentrated in month three or four of the plan year. And we know there's no auto-switching in higher-income groups (because there are no $0 plans). /10

But we do know they'd be concentrated in month three or four of the plan year. And we know there's no auto-switching in higher-income groups (because there are no $0 plans). /10

So we start with a control group: enrollees in the 150-200% tier. (This is 2010, just as an example.)

As expected, we see a very modest amount of switching during open enrollment, but almost none during off-OE months (when you need a qualifying life event to switch). /11

As expected, we see a very modest amount of switching during open enrollment, but almost none during off-OE months (when you need a qualifying life event to switch). /11

Then we add in our treatment group—people in the 100-150% FPL tier, who are subject to the auto-switching policy.

And we see an *enormous* spike in month four.

There's no way everyone is having a QLE at the exact same time—that's going to be (mostly) our auto-switching. /12

And we see an *enormous* spike in month four.

There's no way everyone is having a QLE at the exact same time—that's going to be (mostly) our auto-switching. /12

We see this replicated in 2011 and 2013.

We don't really see it in 2012, though. Why? Because the zero-premium plan stayed the same at the change of the plan year almost everywhere that year! /13

We don't really see it in 2012, though. Why? Because the zero-premium plan stayed the same at the change of the plan year almost everywhere that year! /13

I think this figure tells the story of our paper the most clearly.

Switching spikes *only* occur for people who were in zero-premium plans that became positive premium.

Something—poor awareness, hassle, or affordability—is causing people to lapse on their "new" premiums. /14

Switching spikes *only* occur for people who were in zero-premium plans that became positive premium.

Something—poor awareness, hassle, or affordability—is causing people to lapse on their "new" premiums. /14

And the effect size isn't small. We estimate that 14% of affected enrollees were auto-switched each year.

This is *three times* the share of enrollees actively switching plans during open enrollment.

Policy design should account for inertia, not ignore it. /15

This is *three times* the share of enrollees actively switching plans during open enrollment.

Policy design should account for inertia, not ignore it. /15

In this sample, affordability seems to be part of the problem, but not the whole story.

There's little relationship between premium size and switch rates in our "spike" months. /16

There's little relationship between premium size and switch rates in our "spike" months. /16

Who's getting auto-retained as a result of this policy? (And who might be screened out of the market in its absence?)

We link enrollment record to claims data and find that it's mostly younger, healthier enrollees—people who improve the risk pool. /17

We link enrollment record to claims data and find that it's mostly younger, healthier enrollees—people who improve the risk pool. /17

And recall, under current law these enrollees would likely be terminated for nonpayment.

Part of my dissertation—not yet ready to share widely, unfortunately—finds evidence consistent with this concern (and fairly consistent in terms of effect size) in the post-ACA setting. /18

Part of my dissertation—not yet ready to share widely, unfortunately—finds evidence consistent with this concern (and fairly consistent in terms of effect size) in the post-ACA setting. /18

Inertia and smart defaults are so important to think about as more people become eligible for zero-premium plans—both because of silver-loading and the ARP.

That eligibility can be volatile, depending on how plan bids work out each year and stability of household income. /19

That eligibility can be volatile, depending on how plan bids work out each year and stability of household income. /19

Particularly when policy design *builds in* this kind of volatility—as with the ACA's complicated subsidy scheme—policymakers should be intentional about what policy outcomes are selected as "defaults." /20

In the early days of the ACA, HHS did toy with the idea of renewing people into lower-cost coverage, rather than their same insurance product: cms.gov/CCIIO/Resource…

This hit heavy political headwinds from consumer advocates, who argued that enrollees would be confused, upset.

This hit heavy political headwinds from consumer advocates, who argued that enrollees would be confused, upset.

The auto-retention policy we outline could be more palatable, because these are folks who would otherwise be kicked out of coverage altogether.

But it would also be more limited in scope, applying only to people who qualify for $0 coverage. /22

But it would also be more limited in scope, applying only to people who qualify for $0 coverage. /22

The main question our paper leaves unanswered is what, specifically drives this.

Do people not know they have to switch or start paying premiums? Are logistics of making monthly payments, or setting up auto-recurring payments, a big hassle?

It's probably a little of everything.

Do people not know they have to switch or start paying premiums? Are logistics of making monthly payments, or setting up auto-recurring payments, a big hassle?

It's probably a little of everything.

Health insurance is so dense with administrative burdens, and these can be remedied—at least in part—even as leaders work on more ambitious reforms.

Automatic retention is one policy design that's available and that we know will work. 24/24

Automatic retention is one policy design that's available and that we know will work. 24/24

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh