Our perceptions of some of the things we experience are deeply inaccurate. 🧵

Case 1: The vast majority of restaurants get few visits and go out of business quickly. This seems surprising because the typical restaurant you experience is busy and long-lived.

1/

Case 1: The vast majority of restaurants get few visits and go out of business quickly. This seems surprising because the typical restaurant you experience is busy and long-lived.

1/

The gap between reality and perception happens because few people experience any given unpopular, short-lived restaurant. Precisely because it is unpopular and short-lived!

The brilliant @CFCamerer, who gave this example, notes that it's not just curious but consequential.

2/

The brilliant @CFCamerer, who gave this example, notes that it's not just curious but consequential.

2/

We, including aspiring restauranteurs, undersample unsuccessful restaurants so badly that it can make the restaurant business intuitively feel easy.

So too many people start restaurants who should have done other things instead.

3/

So too many people start restaurants who should have done other things instead.

3/

Maybe this abundance of bad restaurants would help others avoid the same mistake? No: the selection bias, and ignorance of it, are so powerful that it doesn't.

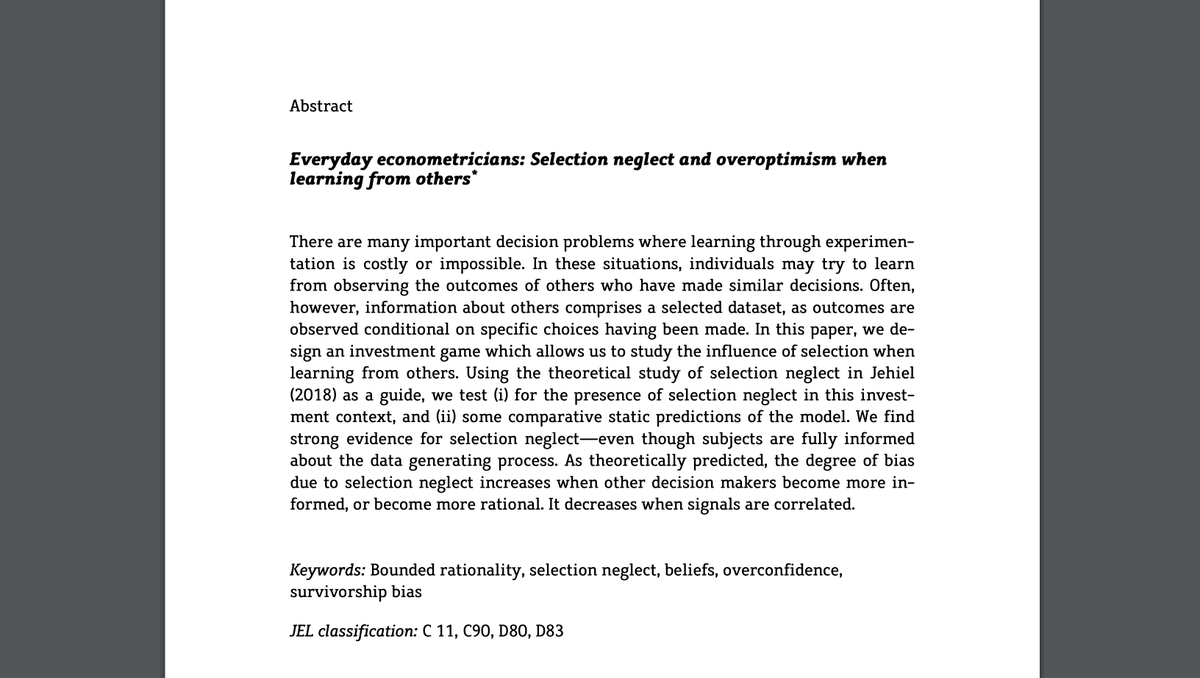

Nice recent paper on this by @kai_barron, @steffenhuck, and Jehiel!

It gets worse.

4/

econstor.eu/bitstream/1041…

Nice recent paper on this by @kai_barron, @steffenhuck, and Jehiel!

It gets worse.

4/

econstor.eu/bitstream/1041…

As the brilliant @4misceldah pointed out in the same conversation, once you do a little math you see that our misperception gets worse the more variance there is in restaurant popularity.

Well, there are many things that make popular restaurants more popular.

5/

Well, there are many things that make popular restaurants more popular.

5/

We hear about good ones from others who have been there. We go with friends. We like to conform and do what's fashionable.

All these effects make the "rich get richer" and create a small number of very popular, profitable restaurants and the most extreme selection bias.

6/

All these effects make the "rich get richer" and create a small number of very popular, profitable restaurants and the most extreme selection bias.

6/

Case 2: music.

Restaurants, like animals, have a natural maximum scale: one can only get so big, limiting the effects above. Not so with music.

The typical song you hear has tens of millions of listens. The typical song made has hundreds of listeners at most.

7/

Restaurants, like animals, have a natural maximum scale: one can only get so big, limiting the effects above. Not so with music.

The typical song you hear has tens of millions of listens. The typical song made has hundreds of listeners at most.

7/

As @CFCamerer, who just happened to run a record label, also points out, if you make an effort to sample SHOWS you find many with a dozen or two listeners. That shows just how popularity (and quality) biased our sampling processes are.

8/

8/

One amusing corollary is that if you ever hear "this is a world premiere" for a piece of classical music and don't have very strong reasons to expect something amazing, you should immediately run the other way.

9/

9/

Most classical pieces that are ever performed are performed ONCE and are not very good.

Our usual sampling process usually protects us from experiencing this part of the distribution. But if you’re told that this protection is somehow off, a Bayesian updates a lot!

10/

Our usual sampling process usually protects us from experiencing this part of the distribution. But if you’re told that this protection is somehow off, a Bayesian updates a lot!

10/

(This makes for a good little problem with Bayes' rule.)

The fact that many of us find implications of sampling biases surprising and counterintiutive suggests there's important behavioral economics to be done about them: even professionals find it hard to adjust for them.

11/

The fact that many of us find implications of sampling biases surprising and counterintiutive suggests there's important behavioral economics to be done about them: even professionals find it hard to adjust for them.

11/

Who knows, though. Most sampling biases you hear about are much more interesting than the typical sampling bias.

12/

12/

For what it's worth, though, I'd never thought properly about either the restaurant or music examples until @CFCamerer's and @4misceldah's comments - right-tail gems hidden in comment threads.

13/13

13/13

PS/ Important caveat. As Chris points out here, restaurants are comparable to other service businesses. I think this does not upset the conventional wisdom that most small entrepreneurs are overoptimistic about the profits of their venture, but certainly

https://twitter.com/conlon_chris/status/1380152152237166592

nuances that point relative to an often-heard factoid.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh