In the next several months we expect measured inflation to increase somewhat, primarily due to three different temporary factors: base effects, supply chain disruptions, and pent-up demand, especially for services. 1/

We expect these three factors will likely be transitory, and that their impact should fade over time as the economy recovers from the pandemic. After that, the longer-term trajectory of inflation is in large part a function of inflationary expectations. 2/

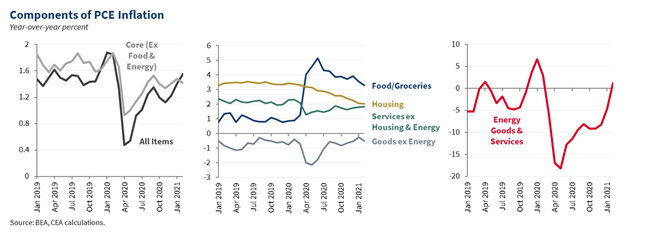

Overall inflation, as defined by the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) deflator, fell during the pandemic, though there have been important differences between products and sectors 3/

In the near-term, we and other analysts expect to see “base-effects” in annual inflation measures. Such effects occur when the base, or initial month, of a growth rate is unusually low or high. 4/

Between February and April 2020, when the pandemic was taking hold in the economy, the level of average prices—as measured by the core PCE deflator—fell 0.5 percent, before beginning to rise again in May 5/

Core PCE inflation leaves out volatile food and energy prices and thus provides a clearer signal of inflation; however, the same base effects are expected to occur in most price series. 6/

This unusually large price decrease early in the pandemic made April 2020 a low base. 7/

Twelve months later, due to the suddenness and scale of this earlier decline, we expect year-over-year inflation growth rates for the next few months to be temporarily distorted by these sorts of base effects. 8/

If we assume monthly inflation going forward stays at a rate of just under 0.2%—the equivalent of a 2 percent annual rate—inflation in April and May 2021, measured as the percentage change in core PCE prices over the previous year, would reach 2.3% due to this base effect. 9/

Not only is that rate higher than recent inflation growth rates, it would represent a sharp acceleration over current core price growth rates 10/

The issue with base effects is not that they make inflation measures wrong; the 2.3 percent year-over-year inflation calculation in our illustrative example would still be correct. 11/

Rather, the base effects distort our understanding of how underlying, near-term trend inflation is behaving right now, suggesting, for example, higher rates of inflation than most analysts expect to persist. 12/

Over the next few months, as the base effects’ months drift further into the past, this distortionary characteristic of the price data should fade. 13/

A second potential source of inflation stems from increases in the cost of production. 14/

If the cost of the materials needed to produce a good or service rises (think lumber needed to build a house or the electricity needed to power a factory), a business may pass on these costs to consumers in the form of higher prices; economists call this cost push inflation 15/

In most cases, this type of inflation is transitory: the price of lumber or energy rises, but then stabilizes at a higher level or decreases, with no further impact on future inflation. 16/

This example underscores an important distinction between price levels and inflation, with the latter being the rate at which levels move up and down. 17/

We have already seen some supply chain disruptions due to the pandemic. For example, the production of parts for goods like automobiles has been curtailed at times, especially in factories in Asia that play an increasingly central role in the global supply chain. 18/

While we expect global supply chains to gradually unclog as world economies recover throughout 2021 and beyond, in the near-term some businesses may temporarily pass on the added costs from these disruptions into higher consumer prices. 19/

Finally, prices for many of the services most sensitive to the pandemic— such as hotels, sit-down restaurants, and air travel—have decreased due to curtailed demand stemming from consumer anxiety and public health restrictions. 20/

As more people get vaccinated throughout the year, however, demand for these and other high-touch services could surge and temporarily outstrip supply. 21/

This surge in demand may in part be fueled by savings many households accumulated during the pandemic, as well as relief payments from the fiscal responses last year and this year. 22/

For example, Americans may have a high demand to eat out in full-service restaurants again later this year, but may find that there are fewer dining options than were open pre-pandemic. That could prompt restaurants that are still open to raise their prices. 23/

While there are natural limits to how many services we can consume quickly—it’s generally only possible for a family to take one vacation at time, for example—Americans may still try to consume these services more frequently, or may upgrade to higher-quality versions. 24/

Economists call inflation resulting from such surges in spending demand pull inflation. 25/

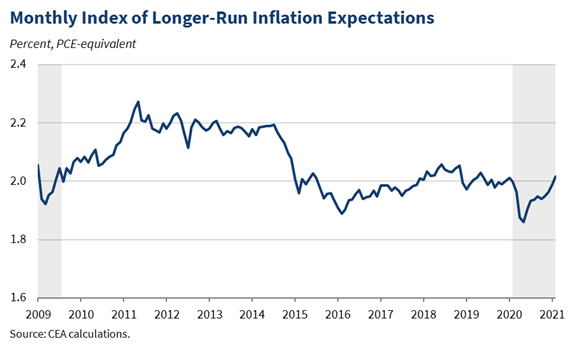

Over the longer-term, a key determinant of lasting price pressures is inflation expectations. 26/

When businesses, for example, expect long-run prices to stay around the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent inflation target, they may be less likely to adjust prices and wages due to the types of temporary factors discussed earlier. 27/

If inflationary expectations become untethered from that target, prices may rise in a lasting manner. This sort of inflationary, or “overheating,” spiral might then lead the central bank to raise interest rates quickly which then slows the economy and increases unemployment 28/

Economists refer to this scenario as “a hard landing,” so inflationary pressures are risks that must be carefully monitored. 29/

It is equally important to recognize that economic “heat” does not necessarily equate with overheating. 30/

We expect that moving from a shutdown economy to a post-pandemic economy—with demand fueled by pent-up savings, relief funds, and low interest rates—will generate not just somewhat faster actual inflation but higher inflationary expectations too. 31/

An increase in inflation expectations from an abnormally low level is a welcome development. But inflation expectations must be carefully monitored to distinguish between the hotter but sustainable scenario versus true overheating. 32/

A monthly composite measure that summarizes 22 different market- and survey-based measures of long-run inflation expectations suggests higher expectations, but the levels of these expectations remain well within historical levels. 33/

We think the likeliest outlook over the next several months is for inflation to rise modestly due to the three temporary factors we discuss above, and to fade back to a lower pace thereafter as actual inflation begins to run more in line with longer-run expectations. 34/

Such a transitory rise in inflation would be consistent with some prior episodes in American history coming out of a pandemic or when the labor market has quickly shifted, such as demobilization from wars. 35/

We will, however, carefully monitor both actual price changes and inflation expectations for any signs of unexpected price pressures that might arise as America leaves the pandemic behind and enters the next economic expansion. /end

The full CEA blogpost is here: whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh