#COVID19India

Quite frankly, I don't (and couldn't know). I've mucked around from simple to ensemble #ML models over the last year, only to realize that something this complex cannot be modelled or predicted.

However, you can pick up what's happening, currently, based...

+

Quite frankly, I don't (and couldn't know). I've mucked around from simple to ensemble #ML models over the last year, only to realize that something this complex cannot be modelled or predicted.

However, you can pick up what's happening, currently, based...

+

https://twitter.com/krishkaran2009/status/1388340476281954305

... off the standard epidemiological metrics - changes in trends, TPR, testing rates, recoveries etc. And what that means in terms of the near and medium-term horizons.

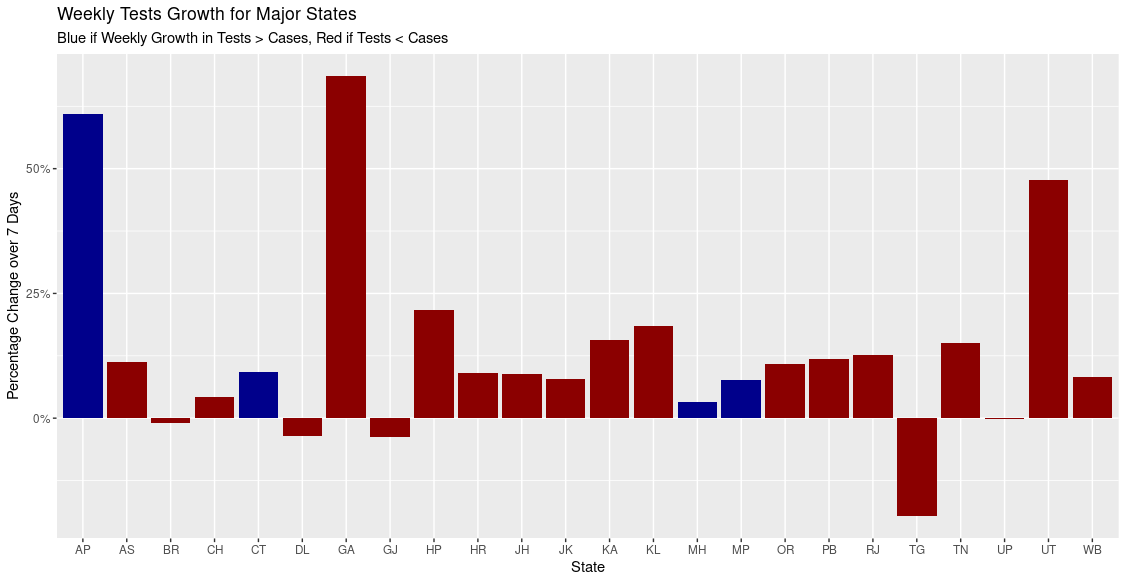

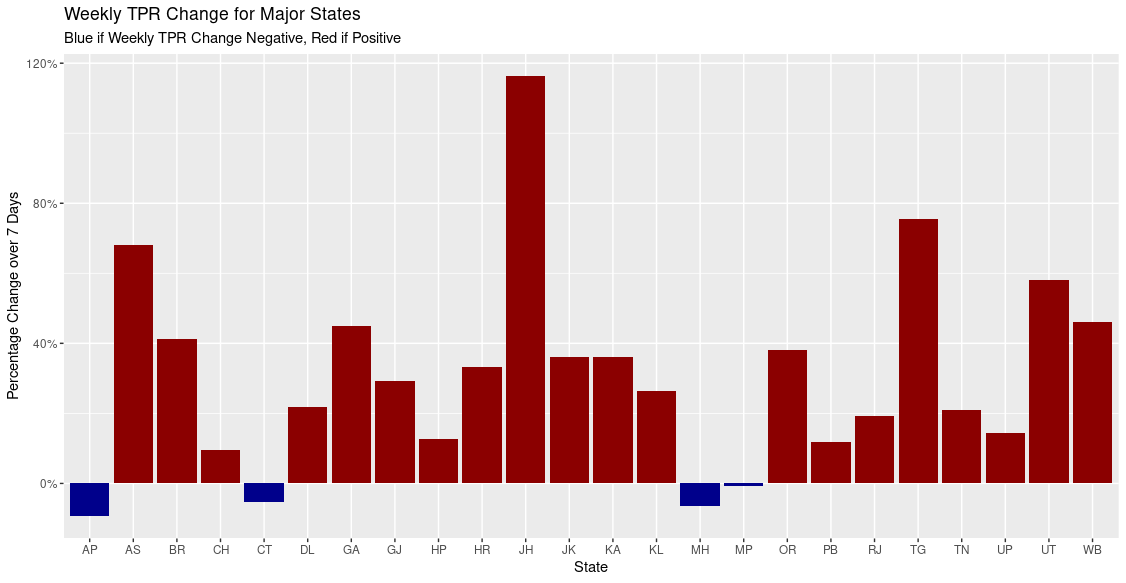

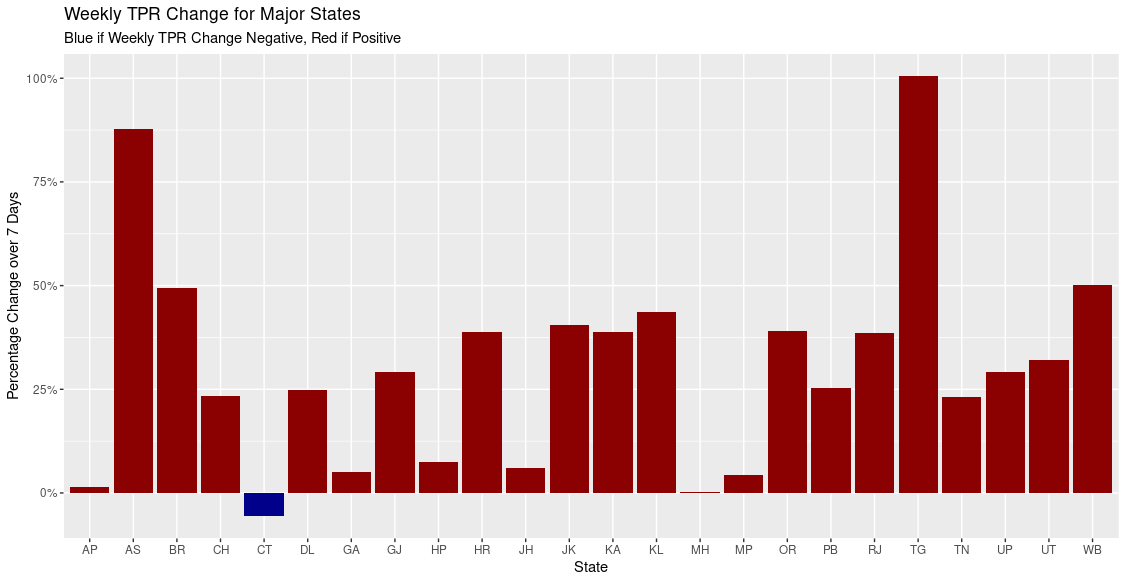

The most sensible benchmark would be TPR declining or levelling off against testing rates that are rising...

+

The most sensible benchmark would be TPR declining or levelling off against testing rates that are rising...

+

... against/ahead of case growth rates. If the data is passably reliable, it's a good indicator that a peak is to be expected, followed by a decline.

This would also show in R[t] hitting 1.0 on a decline and continuing to go under. If testing is doubtful, TPR is rising ...

+

This would also show in R[t] hitting 1.0 on a decline and continuing to go under. If testing is doubtful, TPR is rising ...

+

... cumulative CFR is declining (temporarily) from an asymptotic trend, you don't know what's going on and certainly should not expect a real peak in infection in the region of interest.

Wish I could be more optimistic about this, but I don't see a quick turnaround ...

+

Wish I could be more optimistic about this, but I don't see a quick turnaround ...

+

... regardless of what the daily case numbers suggest.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh