1/ Hedgerows are not only central to our sense of national identity, they're also of immense environmental value. Their loss, and potential for preservation and restoration, also tell the story of our unsustainable way of life and how we can step back from the brink.

2/ Since WWII, the U.K has lost half its hedgerows - a staggering 300,000 miles. Although rates of hedge destruction have been reduced since the high watermark of the 1980s, losses are still occurring due to removal and mismanagement, with huge environmental consequences.

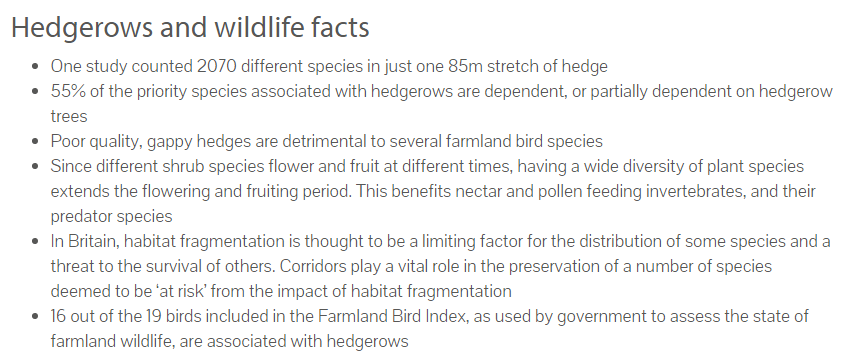

3/ Not only do natural hedgerows reduce resource depletion by eliminating the need for wire and stakes sourced in unsustainable ways, they're also habitat for thousands of vulnerable species, which is why their removal is hastening the collapse of biodiversity.

Via @NBNTrust.

Via @NBNTrust.

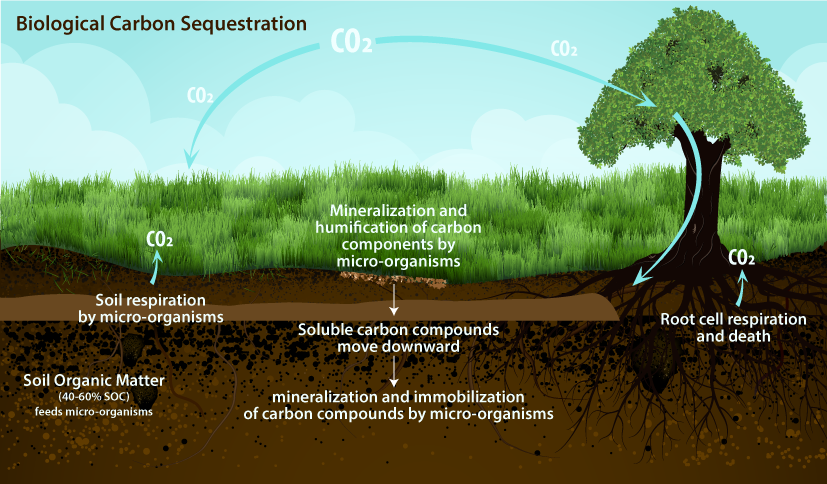

4/ In addition to providing essential, and often irreplaceable biodiversity ecosystem services', hedgerows also sequester vast amounts of carbon dioxide both in above and below-ground biomass. A 100m length of mature hedgerow can sequester in the order of 120kg (0.12t) CO2/year.

5/ Remarkably, the remaining 300,000 miles of native hedgerow in the U.K currently store in the region of 580,000 tonnes of CO2 a year, making them of strategic national importance, which is why the CCC places such emphasis on hedgerow restoration. theccc.org.uk/publication/la…

6/ A planned return to pre-WWII levels of well-managed hedgerows, we could not only absorb/store an additional 600,000 tonnes of CO2 a year, hugely enhancing biodiversity, but (& this is often overlooked) we could also create new, skilled jobs in hedgerow laying and maintenance.

7/ The postwar story of hedgerow loss is one of what I like to call 'destructive efficiency'. Agricultural intensification - and it is consumer demand for cheap food, not farmers, driving this - is the main culprit. Yes, it has marginally increased yields, but at what cost?

8/ The cost of lost hedgerows to our landscape, biodiversity, & CO2 sequestration is clear, but the social and economic cost less so. As you can see from this 1942 Ministry of Agriculture clip, hedge-laying is a highly-skilled, labour-intensive profession.

9/ ...by removing hedgerows, we've not only lost essential hedge-laying skills, but also the rural consumer demand of those who worked to maintain them. Fencing may be 'efficient' for individual farms, but its negative social and economic impacts are profound.

10/ So, reversing the loss of hedgerows is essential for meeting our legally-binding decarbonisation targets, would retard and potentially reverse biodiversity loss, and help breathe life back into dying rural communities through meaningful, sustainable, and skilled local jobs.

11/ Where should we begin? While I do not hold farmers responsible for the loss of the nation's hedgerows, they have big role to play in their return. So, while farmers shouldn't bear the capital costs of restoration, they should be compelled to make their land available.

12/ Since hedgerows - from a biodiversity, CO2 sequestration, social, economic, and landscape perspective - are of strategic national importance, it makes sense that the state should fund the capital and initial revenue (mapping, planning etc) costs of their restoration.

13/ An excellent source of funding for this - including long-term maintenance funding - could also incorporate a CO2 tax trial, hypothecated from a currently 'hard to abate' industrial practice, such as incineration, in order to bridge the gap to Carbon Capture and Storage.

14/ ...and, since real hedge-laying and maintenance is a skilled, labour-intensive activity, funding would be required to train a new generation of hedge-layers through agricultural colleges; though their pay would have a fiscal multiplier of 1.4, generating a net tax increase.

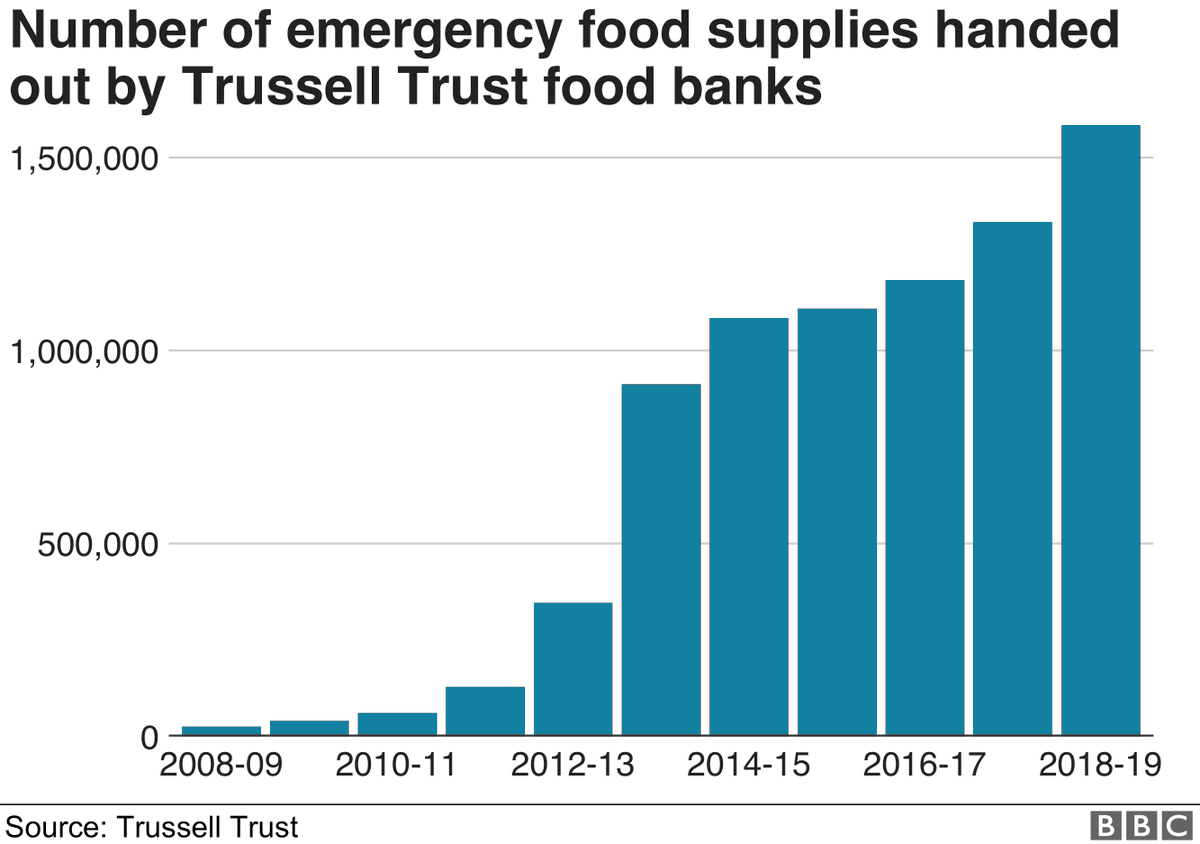

15/ Since I've noted that the removal of hedgerows has marginally increased agricultural yields, it's reasonable to assume that their restoration would reduce yields, potentially imposing increased cash costs for consumers. My response to that is simple - good. And here's why...

16/ We've reduced the price of food dramatically by increasing yields through unsustainable practices, such as hedgerow removal, but has this eliminated food poverty? That's a resounding 'no'. So where is all that food going? In the bins of people who can afford to waste it...

17/ Rather than filling empty bellies, the U.K's surplus food is going to waste, with big environmental impacts:

🍏 13.5 billion '5 a day' portions are discarded annually.

🍞 20 million slices of bread are thrown away daily.

🧀 3.1 million slices of cheese are binned each day.

🍏 13.5 billion '5 a day' portions are discarded annually.

🍞 20 million slices of bread are thrown away daily.

🧀 3.1 million slices of cheese are binned each day.

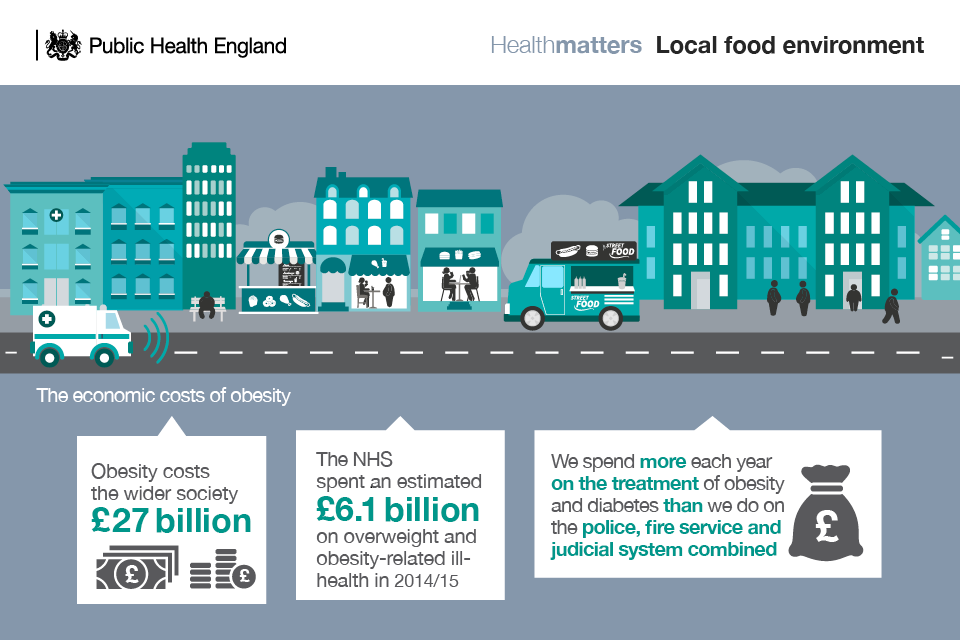

18/ ...and, as we all know, ultra-cheap food also has significant consequences for public health and the public finances...

19/ Increased agricultural efficiency - through practices such as hedgerow removal - has produced enormous costs. Re-evaluating our relationship with the land can deliver immense benefits, vastly reduce costs, and ensure that the remaining ones are distributed more fairly.

20/ Finally, hedgerows aren't just for the countryside. Hedges have been found to out-perform trees in urban settings in some key ways, and are highly versatile for use at locations where the scope for tree-planting is limited. Find out more here... rhs.org.uk/science/garden…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh