Lots of questions still bouncing around on vaccine efficacy vs B.1.617.2, so here are some follow-ups to our Saturday morning story:

Thread follows, and @SarahNev and I published a new story last night covering all the details including transmissibility: ft.com/content/e71471…

Thread follows, and @SarahNev and I published a new story last night covering all the details including transmissibility: ft.com/content/e71471…

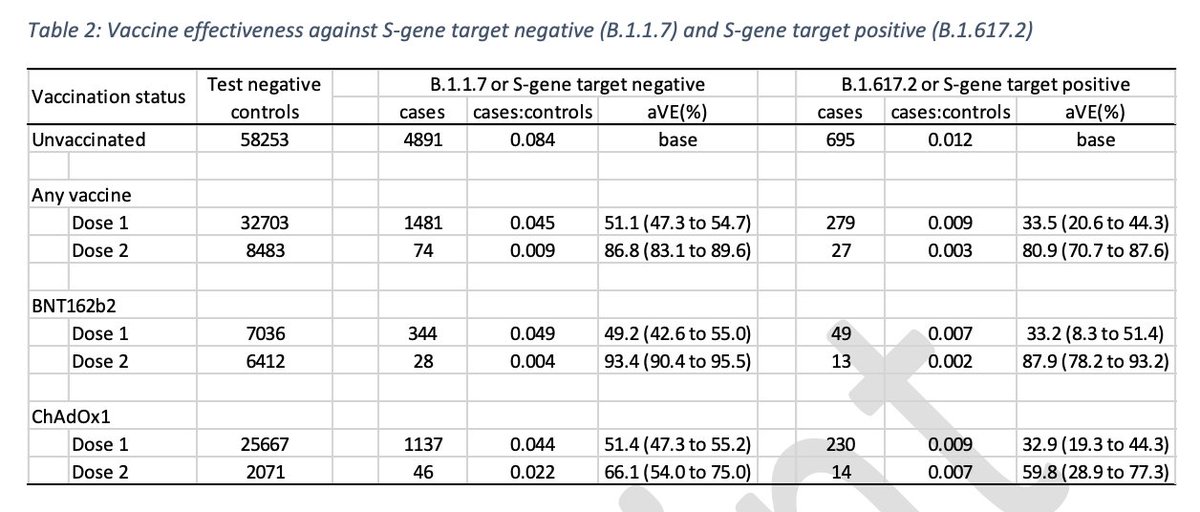

Following our original story, PHE later published more detailed data disaggregated by vaccine.

That data shows our pooled figure of 7% relative drop in two-dose efficacy against B.1.617.2 vs B.1.1.7 comprised a 6% drop for Pfizer, 10% drop for AstraZeneca. Very little difference

That data shows our pooled figure of 7% relative drop in two-dose efficacy against B.1.617.2 vs B.1.1.7 comprised a 6% drop for Pfizer, 10% drop for AstraZeneca. Very little difference

Similarly, the 35% relative drop in efficacy after one dose was virtually indistinguishable between the two vaccines.

A lot of attention has been given to the fact that Pfizer’s relative drop was from 93% to 88%, while AstraZeneca’s was from 66% to 60%, markedly lower figures.

While the attention on 60 & 66 is understandable, it needs interpreting in its proper context:

While the attention on 60 & 66 is understandable, it needs interpreting in its proper context:

First, let’s think about what question the PHE study set out to answer: how much lower is vaccine efficacy against B.1.617.2, compared to B.1.1.7?

(We already know how the vaccines perform against B.1.1.7. We’ve been witnessing their impact in the UK for several months)

(We already know how the vaccines perform against B.1.1.7. We’ve been witnessing their impact in the UK for several months)

And the answer: after two doses, roughly 6% lower for Pfizer, roughly 10% lower for AstraZeneca.

The fact AZ is 60% effective whereas Pfizer is 88% effective is worth noting (and I’ll address that in a minute), but not relevant to the question of relative reduction vs B.1.617.2.

The fact AZ is 60% effective whereas Pfizer is 88% effective is worth noting (and I’ll address that in a minute), but not relevant to the question of relative reduction vs B.1.617.2.

Onto the much-discussed figure of 60% efficacy after two-doses of AZ:

As PHE explained in their study (and we reported last night in our story), that figure shouldn’t be taken as a 'final' estimate of two-dose VE, nor should it really be compared directly to the 88% for Pfizer.

As PHE explained in their study (and we reported last night in our story), that figure shouldn’t be taken as a 'final' estimate of two-dose VE, nor should it really be compared directly to the 88% for Pfizer.

Both of those are for the same reason: the later roll-out of second doses of AZ means less time had passed between second dose and symptom onset for the people in the AZ sample compared to the people in the Pfizer sample. In other words, less time for protection to build.

In addition, second dose sample for AZ is smaller than Pfizer, so more uncertainty around 60 & 66 than around 88 & 93

Of course, that uncertainty could resolve in either direction, but experts we spoke to including report’s authors believe it’s likely 60 & 66 are under-estimates

Of course, that uncertainty could resolve in either direction, but experts we spoke to including report’s authors believe it’s likely 60 & 66 are under-estimates

So overall takeaway from this preliminary vaccine efficacy data remains:

• First dose protection looks be around one-third lower against B.1.617.2, both for Pfizer and AstraZeneca

• Second dose protection holds up pretty well, both for Pfizer and AstraZeneca

• First dose protection looks be around one-third lower against B.1.617.2, both for Pfizer and AstraZeneca

• Second dose protection holds up pretty well, both for Pfizer and AstraZeneca

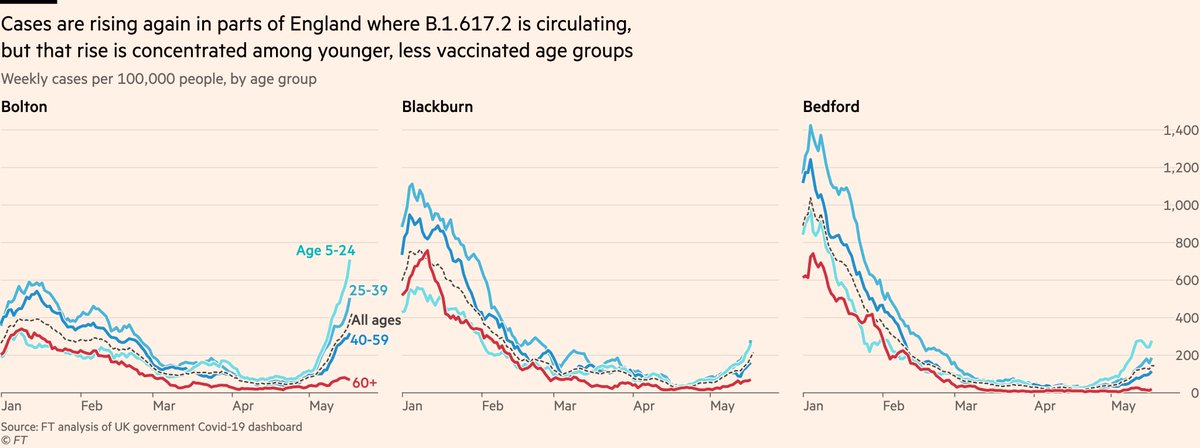

Happily, today’s update of the cases data remains consistent with a solid vaccine effect in areas where B.1.617.2 is dominant.

Cases among older, mostly-double-dosed age groups remain low & stable, while rising among less-vaxxed groups

And remember, most UK jabs are AstraZeneca

Cases among older, mostly-double-dosed age groups remain low & stable, while rising among less-vaxxed groups

And remember, most UK jabs are AstraZeneca

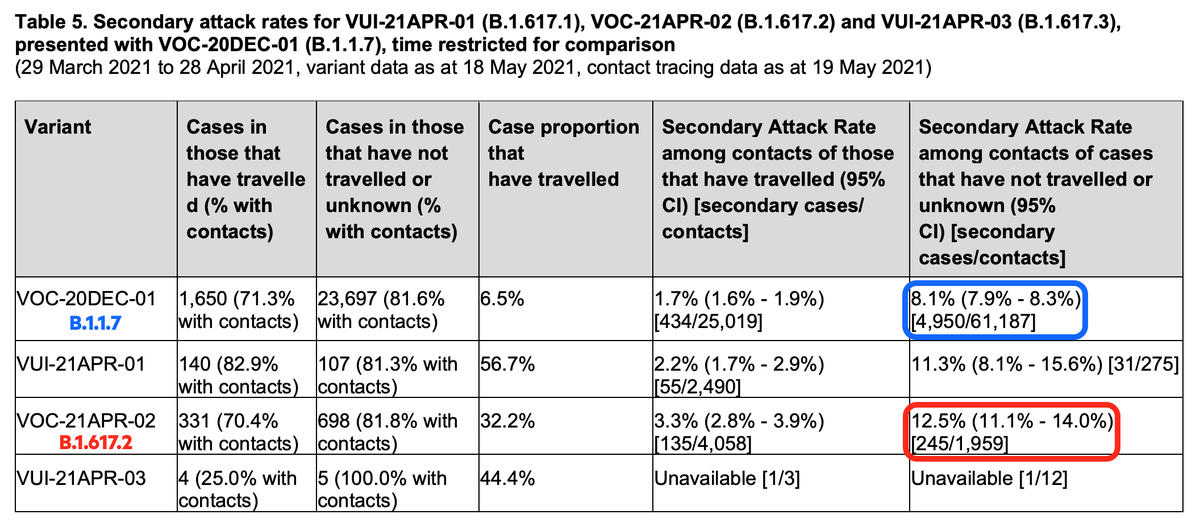

Onto transmissibility: the most significant data point from yesterday’s reports was on secondary attack rates (num of new cases among contacts / total number of contacts)

The data here suggest B.1.617.2 spreads around 50% more easily/widely, but as ever, it comes with caveats:

The data here suggest B.1.617.2 spreads around 50% more easily/widely, but as ever, it comes with caveats:

Part — maybe a very large part — of this will be down to innate, biological characteristics of B.1.617.2, but it can also be influenced by social and behavioural settings where it has spread, and by characteristics of contacts such as vaccinated status (HT @AdamJKucharski)

So on transmissibility we remain in a largely similar place to last week:

• B.1.617.2 does spread more easily

• How much more easily varies by location/cluster, and different clusters have different contexts

• So still very hard to know how much is innate vs context-specific

• B.1.617.2 does spread more easily

• How much more easily varies by location/cluster, and different clusters have different contexts

• So still very hard to know how much is innate vs context-specific

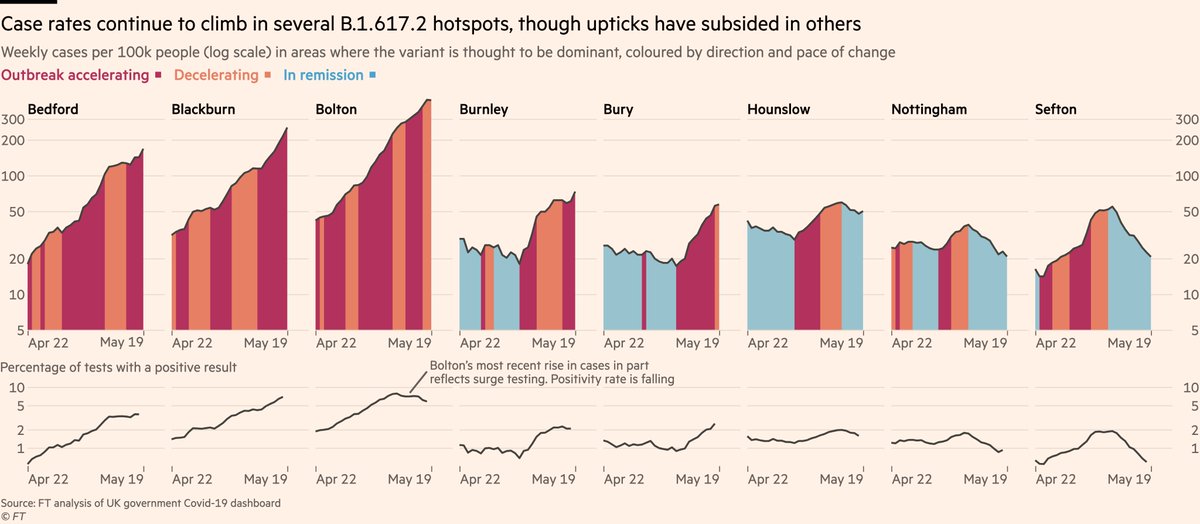

Today’s update of the cases data once again paints a mixed picture:

Case rates in Bolton show signs of stabilising, positivity rate is falling. But numbers in Bedford, Blackburn, Bury still rising.

Certainly evidence here for higher transmissibility, but again context-specific.

Case rates in Bolton show signs of stabilising, positivity rate is falling. But numbers in Bedford, Blackburn, Bury still rising.

Certainly evidence here for higher transmissibility, but again context-specific.

But — again paraphrasing @AdamJKucharski — sitting around waiting for cast-iron evidence doesn’t have a great record over the last 18 months.

Pandemics come at you fast, so decisions often have to be made with less or weaker evidence than we would ideally have.

Pandemics come at you fast, so decisions often have to be made with less or weaker evidence than we would ideally have.

A paper presented to SAGE earlier this month makes the point that while vaccinations remains remain our way out of all this, keeping a lid on transmission while more people get vaccinated will also help. This seems pretty uncontroversial. It’s vaccines *and*, not vaccines *or*.

I’ve talked before about how restrictions, as well as vaccines, have been key to the UK’s declining rates in recent months

Even with second doses providing good protection against B.1.617.2, we shouldn’t pretend they’re the only tool available to us.

https://twitter.com/jburnmurdoch/status/1382013080448724994

Even with second doses providing good protection against B.1.617.2, we shouldn’t pretend they’re the only tool available to us.

So that, really, is the big question right now. What is the *and* that we add to vaccines?

So far it’s been surge-testing in hotspots. There are signs that may already be helping. Giving more agency to local public health teams may also already be helping.

So far it’s been surge-testing in hotspots. There are signs that may already be helping. Giving more agency to local public health teams may also already be helping.

Other options include local lockdowns, more support for isolation, regular rapid testing. None of these implemented yet.

Next level of course would be altering reopening timeline, maybe postponing "full reopening" on June 21. Question is what triggers each additional step?

Next level of course would be altering reopening timeline, maybe postponing "full reopening" on June 21. Question is what triggers each additional step?

So there we are. Lots of stuff there but hopefully worth the time to paint a comprehensive picture.

Enjoy the remainder of your Sunday, folks.

Enjoy the remainder of your Sunday, folks.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh