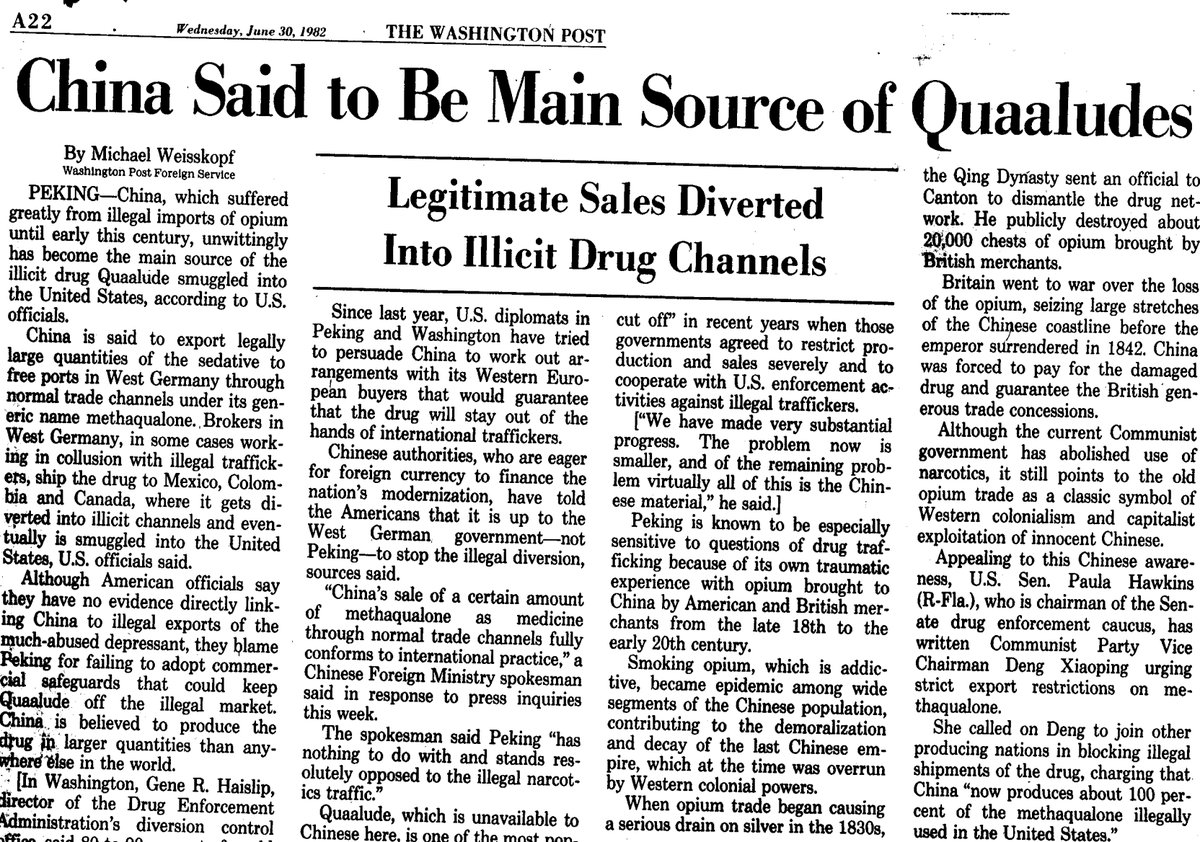

I'd never heard of the claim that China was flooding America with methaqualone in the '80s, pushed by Reagan friend and drug warrior Paula Hawkins. Her later claims to have demanded to Deng Xiaoping's face that he stop selling dope helped Bob Graham defeat her in 1986.

By 1986, Qualuudes had been taken off the market and methaqualone was rescheduled to make it completely illegal. The market for bootleg pills was evaporating. Paula Hawkins here describes the "yellow trail of methaqualone": c-span.org/video/?150709-…. Might be true. I don't know.

By 1990, when Larouche publication Executive Intelligence Review raised the specter of "Communist Quaaludes for America," I don't know if you could still find fake Quaaludes. Maybe you could. The idea of Kissinger facilitating Deng's narco-state is fun, though.

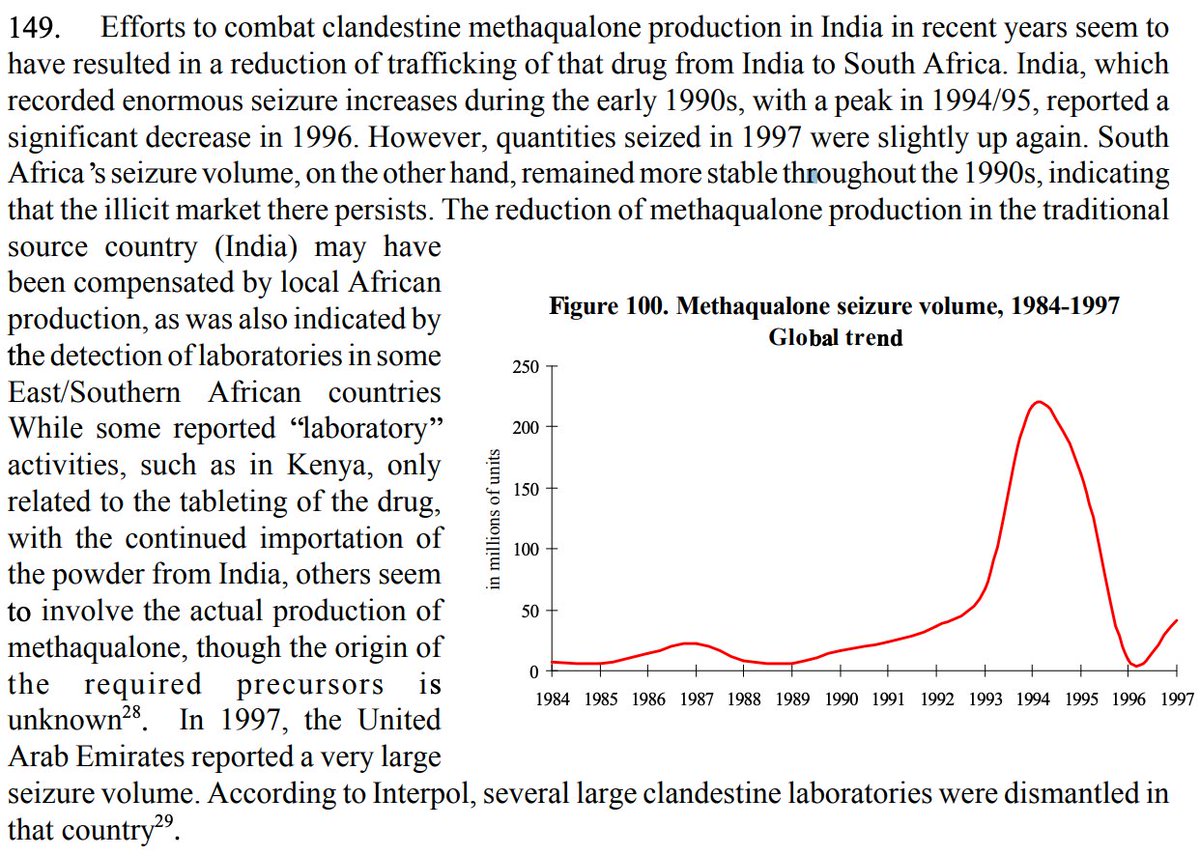

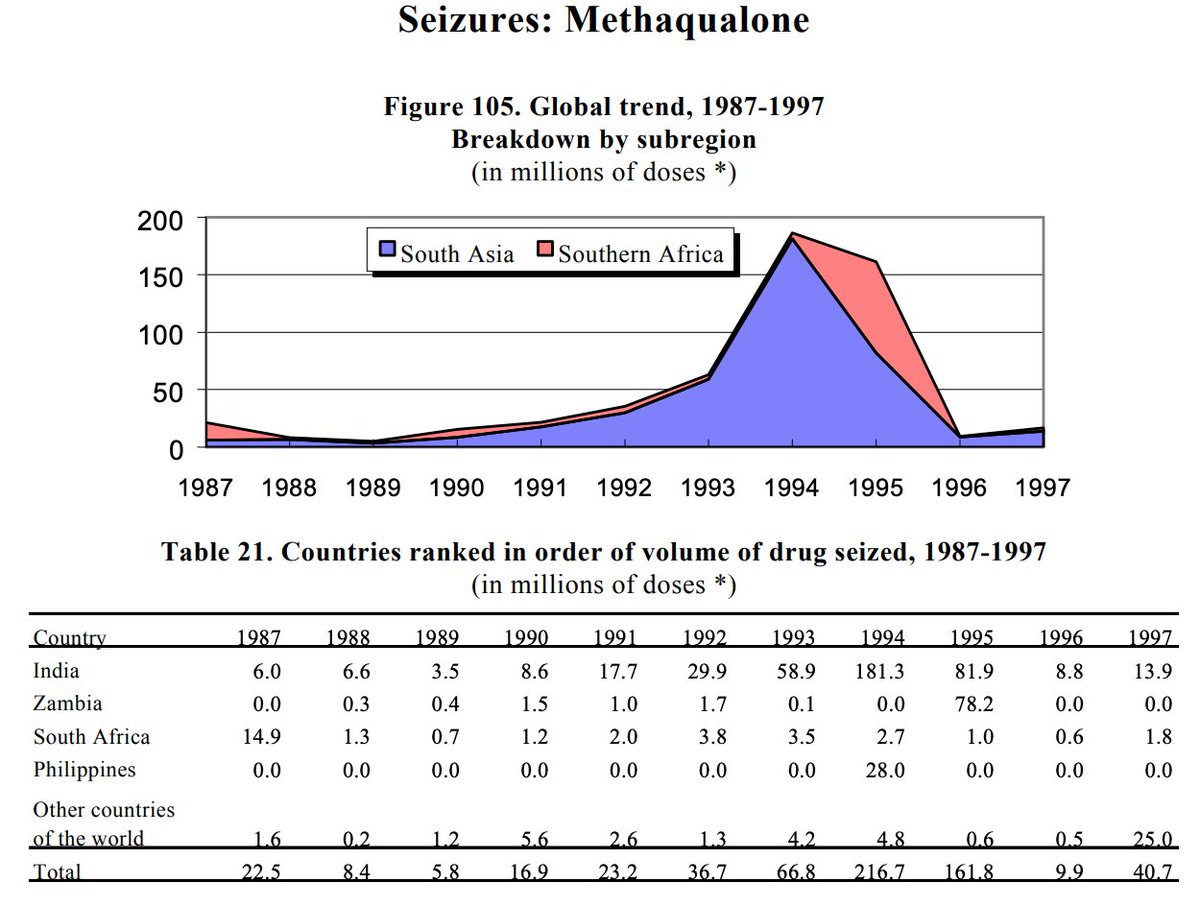

You would struggle to find methaqualone in the United States, but that's not to say it's disappeared completely. The market changed. It started to Africa and the Middle East. Like with ketamine, another illicit drug associated with China, India was usually the source.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh