1/9 Thread: Retention rate illusions

With the rise of SaaS businesses, retention rate is often discussed and followed by investors.

Here are some of the notes I took from an academic paper discussing illusions/misconceptions when it comes to retention rates.

With the rise of SaaS businesses, retention rate is often discussed and followed by investors.

Here are some of the notes I took from an academic paper discussing illusions/misconceptions when it comes to retention rates.

2/9 Issue #1: Reported retention rate may not be indicative of realized renewal rate. Let me give an example.

Let’s say a business reports retention rate is 95% which is, of course, awesome. What is less discussed, however, is the duration of the customer contracts.

Let’s say a business reports retention rate is 95% which is, of course, awesome. What is less discussed, however, is the duration of the customer contracts.

3/9 To illustrate why it is important, imagine Company A, B, and C all report 95% retention rates, but customers only renew the contracts in every 1, 3, and 5 year respectively.

Here’s how the reported and underlying retention rate differs for these companies.

Here’s how the reported and underlying retention rate differs for these companies.

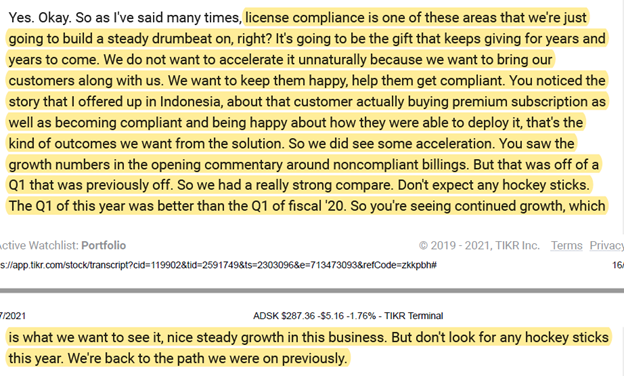

4/9 “without knowing the duration of the contract, it is very hard to indicate whether these high retention rates are the result of a high renewal rate or driven by the inability of customers to cancel their contract.”

5/9 Issue #2: Companies can *temporarily* increase retention rates by providing discounts

If a business has high customer retention rates but low revenue retention rates, it may be indicative of steep discount the company is providing its customers to window dress.

If a business has high customer retention rates but low revenue retention rates, it may be indicative of steep discount the company is providing its customers to window dress.

6/9 Issue #3: If customers are not homogenous, historical retention rate may not be indicative of future retention rate.

Retention rate is likely to be different when you acquire customers organically vs advertisement or promotional offers.

Retention rate is likely to be different when you acquire customers organically vs advertisement or promotional offers.

7/9 Issue #4: When a company takes an ecosystem/platform approach and creates a diversified product portfolio, switching cost can incrementally increase.

In this case, future retention rate can be higher than historical one.

In this case, future retention rate can be higher than historical one.

8/9 Issue #5: Important to understand whether retention rate is reported on an annual basis or monthly basis.

When a company reports 90% retention, if they report annual retention, it means 10% churn, but if it means monthly retention, it may mean 72% churn on an annual basis!

When a company reports 90% retention, if they report annual retention, it means 10% churn, but if it means monthly retention, it may mean 72% churn on an annual basis!

9/9 Link to the academic paper: papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

All my twitter threads: mbi-deepdives.com/twitter-thread…

All my twitter threads: mbi-deepdives.com/twitter-thread…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh