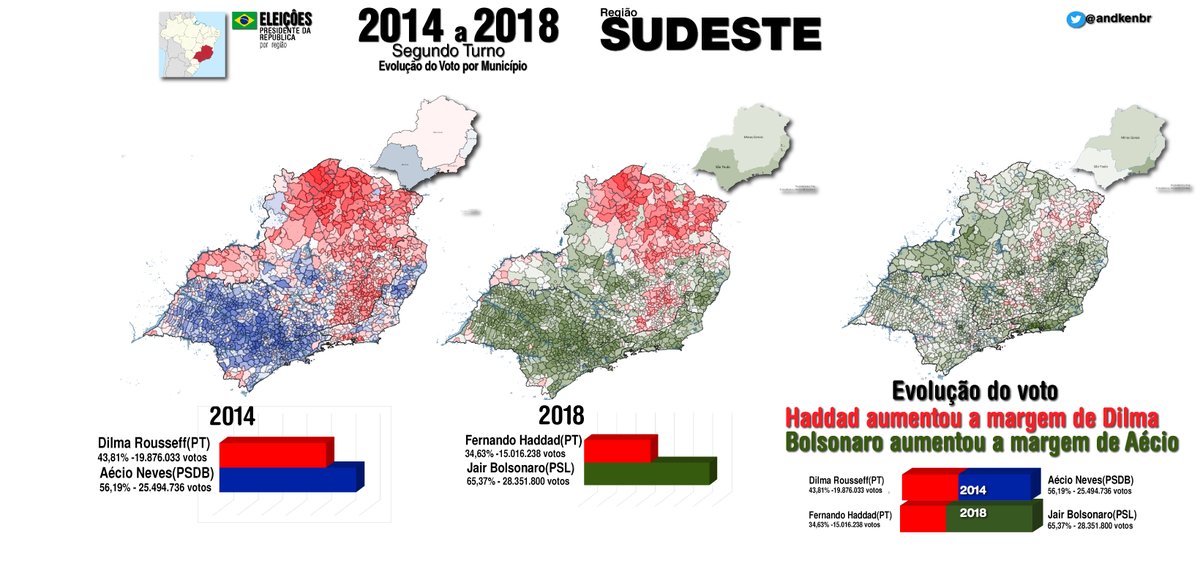

#ElectionTwitter(International)- Now, continuing the maps of the last two Presidential elections in Brazil: the Southeast, the most populated region in the country.

Versão em português do fio, thread, novelo, como vocês preferirem:

https://twitter.com/andkenbr/status/1400692282546872322

When foreigners think about a specific place in Brazil they are probably going to think about somewhere in the Southeast. Both São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro are there. Between one third to half of the population of Brazil lives in the region (80 of 220 million).

Small swings of voters in the Southeast can move a lot of voters nationally. And the ultimate bellwether state in Brazilian politics – Minas Gerais – is part of the region.

Minas Gerais, the second largest state in Brazil, only failed to vote for the winner of a free and full presidential election once, in 1950(There wasn’t a runoff, and a local candidate syphoned votes from Getulio Vargas, the winner).

In the first decades of the Republic landowners from São Paulo and Minas Gerais used machine politics (and vote manipulation) to alternate in the Presidency, in what was called Milk Coffee Republic, a reference to the production of coffee in São Paulo and milk in Minas Gerais.

(Ironically, Minas Gerais would become the largest producer of coffee in Brazil). With exception of Hermes da Fonseca and Nilo Peçanha the Brazilian presidents from the first three decades of the century would come from these two states.

Yes, without an Electoral college the person that wins the state doesn’t matter that much, as we will see there are four or five major regions in that state that are politically very different from each other. But I can’t see how you can win the presidency without Minas Gerais.

Not only Minas Gerais is large: if you are losing the North of the state you are not winning the Brazilian Northeast. And if you are losing in the South you are not winning in São Paulo and in large parts of the rest of the country.

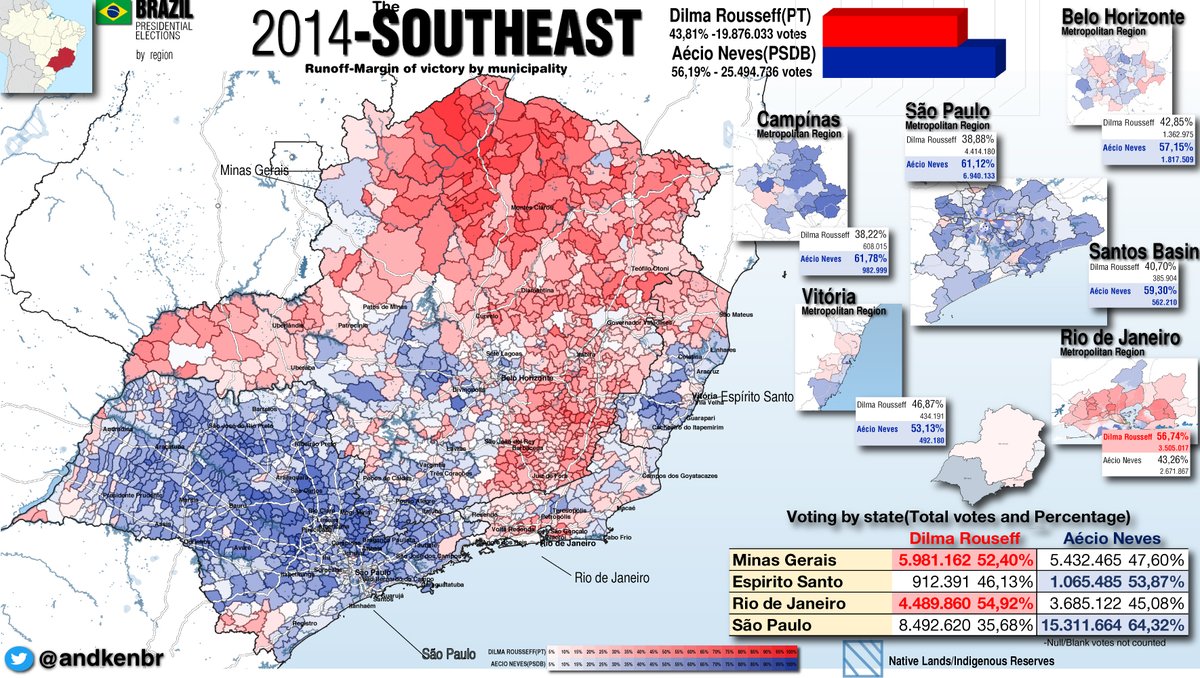

In 2014, Dilma Rousseff would manage to win Minas Gerais by a relatively small margin. Running against favorite son Aecio Neves (former governor and then senator) she would lose in the capital, Belo Horizonte, while winning in the panhandle (Triangle), North and Southeast.

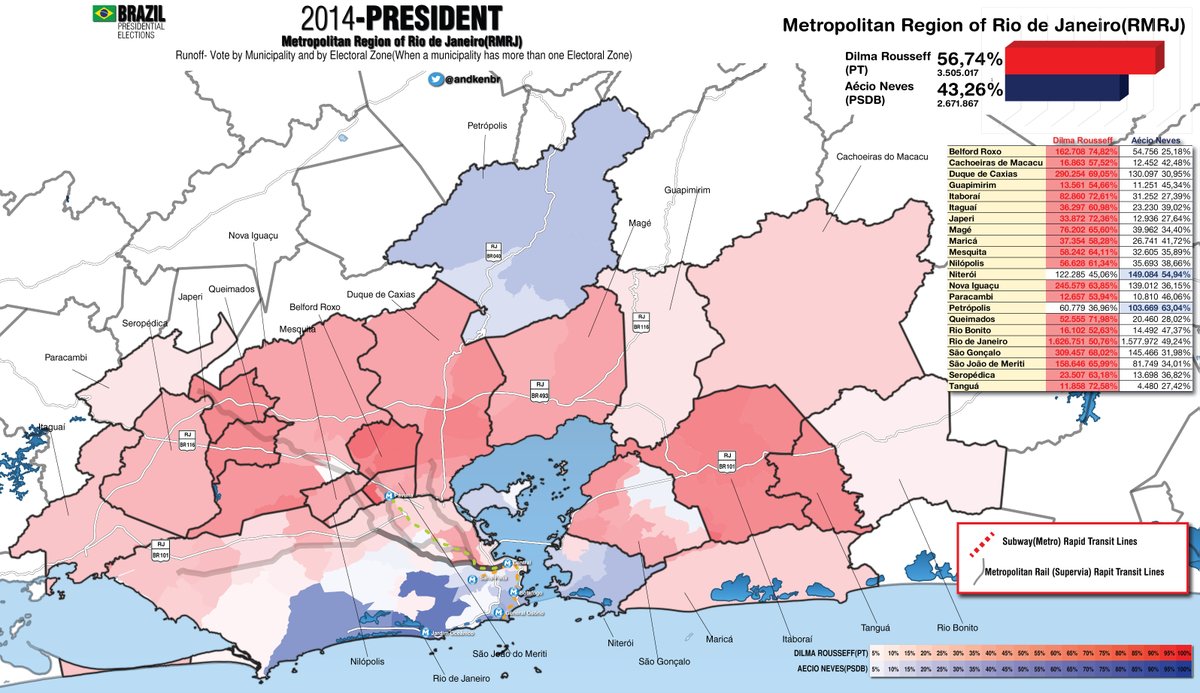

Dilma also managed to win the state of Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro has a tradition of having politicians with national ambitions that fail to attract votes outside the state. She won in the metropolitan region of Rio, with comfortable margins in the outskirts

Dilma won the largely working-class neighborhoods in Rio. She lost in two more upper class suburbs, Petropolis and Niteroi, and in the central area of the city of Rio. But she won everywhere else.

In São Paulo it was very clear to see one of the largest vulnerabilities of the Brazilian left: the erosion of the vote among lower-income classes in the urban areas in the South and Southeast. She lost in the industrial and working class suburbs of São Paulo.

These suburbs were a stronghold of the party, that was basically founded there. Dilma was already losing all of them. She lost São Bernardo, where Lula made his career as a union leader in the late 70’s.

She also lost big in the region of Santos, that hosts the largest port in Latin America. She lost in Campinas, the second largest metropolitan area of São Paulo, with lots of industries and universities, in theory, a perfect place for a center-left party.

In 2018 Fernando Haddad, Lula’s anointed successor would watch his party lose a large share of the vote in three states in the Southeast, especially in Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro. That in large part would explain why Bolsonaro won the national election.

The region is known for the beef and milk production, and it wouldn’t the only Brazilian region relying on agriculture to flip to the right. Or the state. Bolsonaro would also make gains in the southeast of the state(coffee).

The Workers Party would keep their stronghold in the North of the State – the poorest region in the state, and economically and culturally very similar to the Brazilian Northeast. But they would also bleed votes there.

In an example of the rural bias of the vote for the Workers Party they would lose in two of the largest cities in the North of Minas Gerais – Teofilo Otoni and Montes Claros. It’s the same bias that we saw in the North and the Northeast of Brazil.

There is a “red wall” for the Workers Party, including the Northeast, parts of the North and the North of Minas Gerais. These losses point out to one of the dilemmas of Brazilian politics: how strong and how durable is this wall? Are we seeing some cracks there?

The biggest bleeding for the Workers’ Party would be Rio de Janeiro. Bolsonaro is the first politician from Rio that manage to become a viable national candidate in a long time. In 1989, Leonel Brizola, the them governor, came about 1% of going to the runoff, but that was it.

Eduardo Gomes, a brigadier general from the Air Force, would be runner-up in 1945 and 1950, but he was never elected to office. Useless trivia: brigadeiro, the children’s candy, is named after Gomes, a very conservative general that would be part of the Military Regime of 1964

Fernando Haddad would win in only three municipalities in the entire state (All of the three with population of 10,000 or less) and would lose ground in all municipalities of the state. The bleeding is notable in the Metropolitan Region of Rio de Janeiro.

There was a swing of more than 40 points in a lot of municipalities in the Metropolitan Region of Rio de Janeiro. That’s not something that we see very often, frankly, I needed to look into Depression year elections in the US to find something close.

Dilma only lost two municipalities around the city of Rio de Janeiro. Under Haddad, that would be completely reversed. To me, the big question is: how much about this is Rio moving to the left? And how much is about –finally-having a competitive candidate for President from Rio?

There is a favorite son effect for Bolsonaro, but a lot of the favelas in Rio are controlled by right-wing militias and neopentencostal churches. A cynical might argue that a lot of this rightward shift of Rio de Janeiro is due to these militias, that directly extort citizens.

There are physical risks for leftist politicians campaigning in favelas (Hate him, but Glenn Greenwald definitely has a point there). Coincidence or not, city councilmember Marielle Franco was basically one of the few politicians of the left that manage to get votes in the favela

And she was killed in cold blood in a crime that wasn’t solved to this day.

The question: considering both the criminal and political climate, is that – and how much of that – reversible?

The question: considering both the criminal and political climate, is that – and how much of that – reversible?

In São Paulo, Haddad gained ground in some districts in poorer regions of the city of São Paulo but would bleed support in the industrial suburbs. He would win by small margin a single municipality – Francisco Morato – the suburb with lowest income in the metropolitan region.

A similar corrosion could be seen in Campinas, where Haddad lost all the municipalities there. Including low income and industrial suburbs.

These losses are something emblematic. These are the Brazilian equivalents to places like Newark, East Saint Louis, Baltimore and Detroit. Imagine a Democrat losing these places, and by large margins.

The Workers Party was founded in Santo Andre and São Bernardo, and Haddad lost big in these two municipalities. It’s very painful to watch. On the other hand, it’s difficult to imagine the Brazilian Left bleeding more votes in the large cities of the Southeast.

The urban problems of the Workers Party aren’t limited to São Paulo and Rio. They lost all the municipalities in the Metropolitan Region of Belo Horizonte (Including industrial cities of Betim and Contagem, where the party has lot of History), except for four rural municipalities

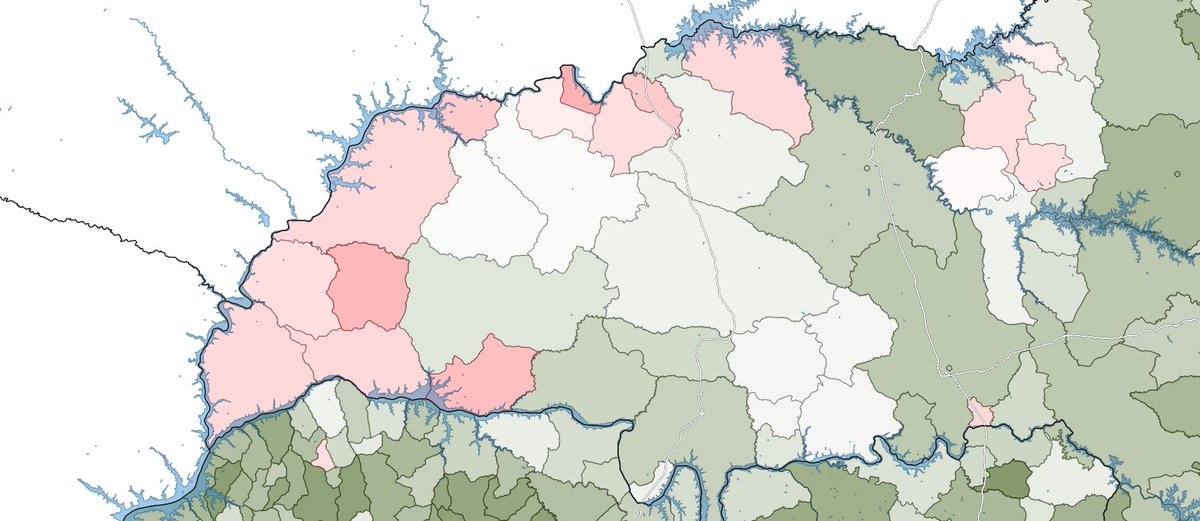

Looking into the swing of the vote, we can see Haddad gaining ground in the city of São Paulo and other rural municipalities. He would lose ground in all municipalities in the states of Rio de Janeiro and Espirito Santo, with a single exception.

In the state of São Paulo, Bolsonaro got less votes than Aecio Neves did, but increased over his share of the vote by 3.65%. Almost two million less votes in the states of Minas Gerais and São Paulo, an astonishing number in a country where voting is theoretically mandatory.

This blend of cynicism and apathy is a very overlooked problem of Brazilian politics, and it’s easy to see less people voting year after year. And that’s in part explain why the country is trending right.

In the Metropolitan Region of São Paulo Haddad gained votes in a lot of parts the outskirts, in part because Dilma had already bled a lot of votes there. But he also made gains in some older parts of the downtown area and other central areas.

In Rio, where Bolsonaro was a more known quantity we can see him losing ground in the more central areas, where the places that tourists know are located (It’s easy to see that looking into the Subway lines in the map).

In the Metropolitan area of Campinas of the few places where Haddad gained votes is north of Campinas, that has upper scale suburbs and where the main universities are located.

Could we be watching a division of the vote closer to what we see in the United States and Europe, with educated voters trending left?

Or that the Brazilian Left is going to see small gains with educated voters but that’s not going to be enough to compensate for losses with working class voters?

Bolsonaro is a very unusual candidate, and these regions are still very conservative. But that’s a good question about the future of politics in Brazil. In a few weeks we’ll check the South of Brazil, the last one of this series.

A look in how the vote changed in four years, first, at regional level:

Now, in the Metropolitan Area of Rio de Janeiro:

Finally, in in the Metropolitan areas of São Paulo and Santos.

The other regions in the series: North-

https://twitter.com/andkenbr/status/1292984584087441412

Central-West:

https://twitter.com/andkenbr/status/1312936550385188869

Finally, thanks for the #ElectionTwitter community for the inspiration, specially Mr. @JMilesColeman and @DrewSav.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh