🆕 #archaeology: People in early medieval Europe kept reopening graves. What was thought to be isolated events, like grave robbing, is actually a regular part of funerary traditions from the 5th – 7th c. AD

Here's an #AntiquityThread on the work (🆓) buff.ly/3wLOSuE 1/🧵

Here's an #AntiquityThread on the work (🆓) buff.ly/3wLOSuE 1/🧵

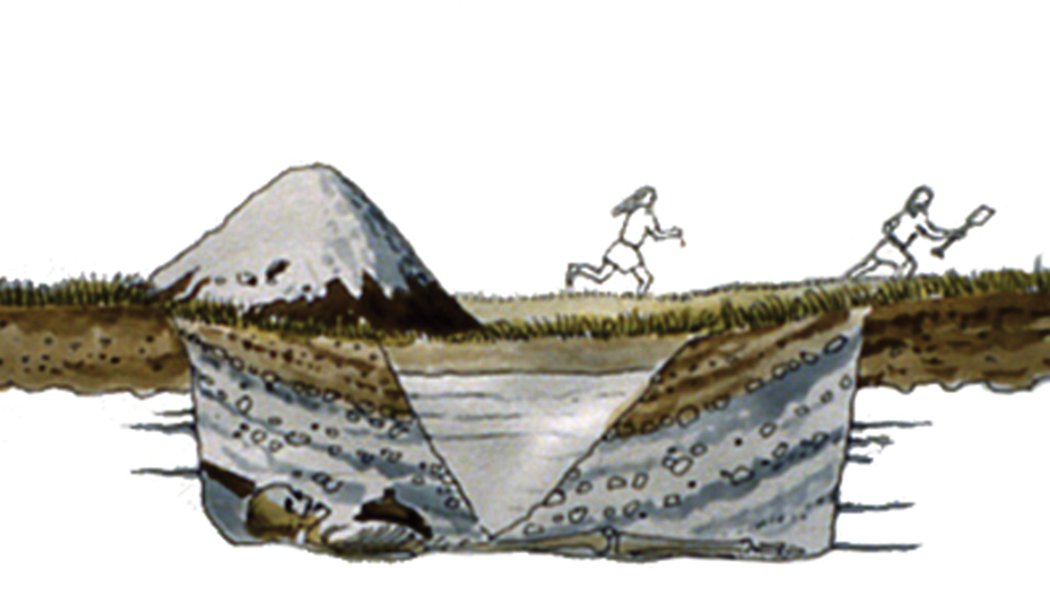

📷: Reconstruction of a chamber grave from eastern France

Note: This thread may feature some skeletons 2/

Note: This thread may feature some skeletons 2/

“For over 100 years, archaeologists in many European countries have discovered graves from the early medieval period which look like they were robbed... 3/

📷: Very small grave robbers, by L. Jay, courtesy of the Trust for Thanet Archaeology.

📷: Very small grave robbers, by L. Jay, courtesy of the Trust for Thanet Archaeology.

"...But over the decades, many excavators have realized that something stranger is going on,” said Dr Alison Klevnäs 4/

📷: Grave from France where the individual was moved around before he fully decomposed, by Éveha-Études et valorisations archéologiques, by G. Grange

📷: Grave from France where the individual was moved around before he fully decomposed, by Éveha-Études et valorisations archéologiques, by G. Grange

As such, Dr Klevnäs and four other archaeologists studying this phenomenon in different parts of Europe pooled their data to investigate what was going on. 5/

📷: Archaeologists reopening reopened graves, by L. Jay, courtesy of the Trust for Thanet Archaeology

📷: Archaeologists reopening reopened graves, by L. Jay, courtesy of the Trust for Thanet Archaeology

Their analysis showed for the first time the huge scale of grave reopening.

They found it was a widespread and long-lasting practice, uncovering >1000 reopened graves across dozens of cemeteries, from Transylvania to England. 6/

📷: Map of cemeteries with grave reopening.

They found it was a widespread and long-lasting practice, uncovering >1000 reopened graves across dozens of cemeteries, from Transylvania to England. 6/

📷: Map of cemeteries with grave reopening.

“The reopening custom spread over western Europe from the later sixth century and reached a peak in the seventh century... 7/

📷: Plan of the excavated part of the cemetery at Posterholt-Achterste Voorst, the Netherlands

📷: Plan of the excavated part of the cemetery at Posterholt-Achterste Voorst, the Netherlands

“In most areas, it peters out in the later seventh century, so that many cemeteries have a last phase of burials with no reopening,” said Dr Astrid Noterman, who studied sites in northern France. 8/

Crucially, these findings reveal reopening graves was likely not a case of grave robbing as analysis revealed a pattern of careful object selection not focused on value. 9/

“They made a careful selection of possessions to remove, especially taking brooches from women and swords from men, but they left behind lots of valuables, even precious metal objects, including necklace pendants of gold or silver,” said Dr Klevnäs 10/

Instead, this was a regular part of mortuary customs. Most of this reopening appears to have taken place before the coffins had fully decayed – people returning to the graves of their parents or grandparents generation. 11/

📷: A grave where bones were moved in the coffin

📷: A grave where bones were moved in the coffin

However, whilst reopening graves was a widespread part of life in early medieval Europe there was variation, perhaps based on local traditions or even who was buried. 12/

📷: Signs of cutting common at Vendenheim, France

📷: Signs of cutting common at Vendenheim, France

Most disturbances involved removing selected objects, but other activities include manipulating the dead, damaging objects, removing body parts, and in one case adding a dog to the burial. 13/

📷: Archaeologists can confirm they were a good boi

📷: Archaeologists can confirm they were a good boi

“Robbing graves sounds like a negative act, but it actually seems to be socially positive here. People carried on burying the dead in cemeteries, alongside repeated events of reopening graves...” 14/

“...We can even see that some cemeteries with reopening customs were used for longer than ones where the dead were left in peace,” said Dr Klevnäs. 15/

Now that this practice has been identified, it is hoped further research can shed more light on it – including investigating why it spread across such a large region over a short space of time. 16/16

Find out more in the original research (🆓) published today in Antiquity:

Reopening graves in the early Middle Ages: from local practice to European phenomenon - Alison Klevnäs, Edeltraud Aspöck, Astrid Noterman, Martine van Haperen & Stephanie Zintl

doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2…

Reopening graves in the early Middle Ages: from local practice to European phenomenon - Alison Klevnäs, Edeltraud Aspöck, Astrid Noterman, Martine van Haperen & Stephanie Zintl

doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh