What risks does #climatechange pose for government finances? 🌍

OBR Economists Rachel and Tom explain some of the risks we’ve considered in chapter 3 of our 2021 #OBRfiscalrisks report 📗

Read more: obr.uk/frr/fiscal-ris…

OBR Economists Rachel and Tom explain some of the risks we’ve considered in chapter 3 of our 2021 #OBRfiscalrisks report 📗

Read more: obr.uk/frr/fiscal-ris…

The Government has committed to achieving net zero by 2050. Since 1990, the UK has cut its CO2 emissions by 243 million tonnes, more than any other G7 economy and faster than the EU average.

#OBRfiscalrisks

#OBRfiscalrisks

But the UK will need to cut emissions by another 365 million tonnes over the next 30 years to reach net zero emissions by 2050. The reductions will need to come mainly from decarbonising power, industry, buildings, and transport.

#OBRfiscalrisks

#OBRfiscalrisks

The total cost to society of achieving net zero could be significant, with £42 billion a year of investment required to decarbonise power generation, household & commercial heating, and manufacturing.

#OBRfiscalrisks

#OBRfiscalrisks

The shift from fossil-fuel-driven to electric vehicles, on the other hand, offers the prospect of both lower emissions and financial savings thanks to lower running costs. This may be one reason why take up of electric cars has consistently outpaced our forecasts.

Fewer fossil-fuel-driven cars, which will be banned from sale in 2030, will erode £35 billion a year (1.5% of GDP) of fuel duty and VED receipts. This could be, temporarily, offset by taxing carbon more heavily, which could also help pay for some of the transition costs.

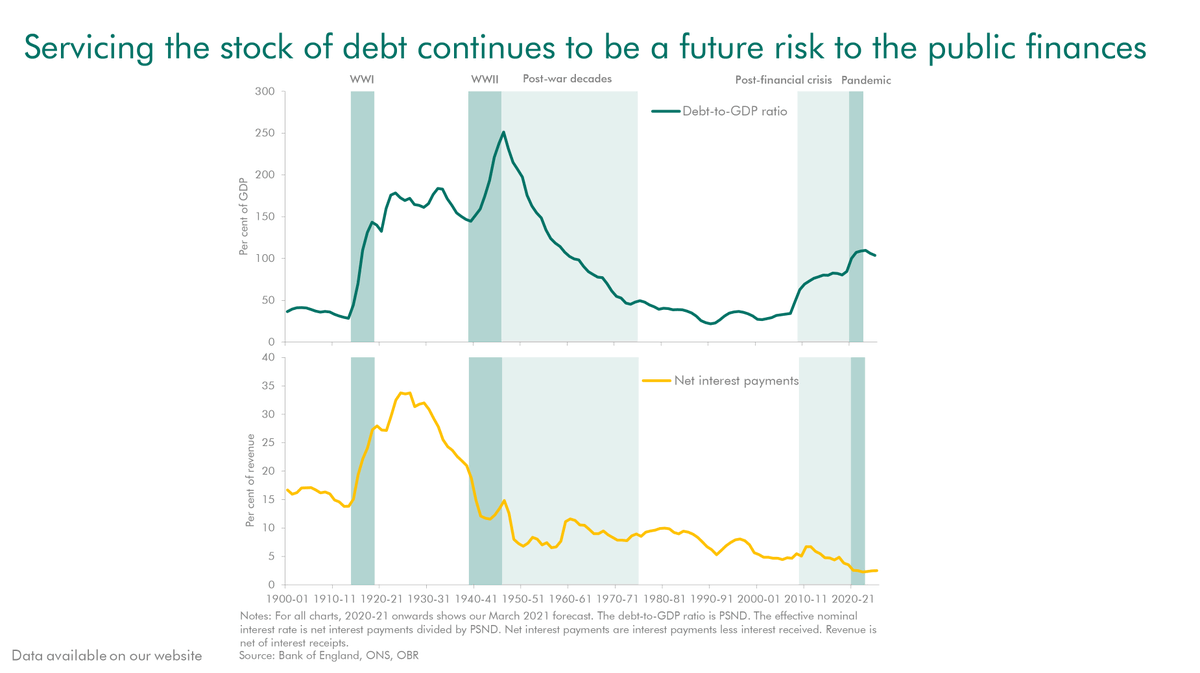

The #OBRfiscalrisks report draws on @theCCCuk and @bankofengland scenarios to estimate the net fiscal impact of reaching net zero by 2050. An early action scenario adds 21% to the debt/GDP ratio – a lot, but less than either the 2020 pandemic or the 2008 financial crisis.

The economic and fiscal consequences of getting to net zero are uncertain, and there are choices about how much of the cost is borne by the state vs. households and businesses. We therefore consider alternative scenarios and sensitivities and their effect on debt. #OBRfiscalrisks

Policy settings are crucial to the long-term fiscal impact of getting to net zero. Debt falls below our baseline if net zero transition costs are funded from within existing public investment plans and fuel duty is replaced by another tax on motoring.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh