Military Intelligence involves the collection of information by commanders on the enemy and the battlefield environment and other related information necessary for effective planning and decision-making.

Traditionally, Military Intelligence was an activity that was primarily conducted during wartime and was not something deemed worthy of specific training or specialization – it was “considered a function of command, one which any professional officer could perform.”

“Commanders tended to be skeptical about the reliability of the information they received from spies, scouts, and their own troops.”

Clausewitz, in On War, “commented only that many intelligence reports in war are contradictory, even more are false, and most are uncertain.”

But that’s the funny thing about Intelligence – information is gathered, analyzed, and judgements or assessments are made, and those assessments are often just the “best guess” based on the information available and a bunch of assumptions.

Early in American history, if the country was not at war there was no perceived need for Military Intelligence efforts. In the 1800s, the European militaries began reorganizing with general staffs and this process provided an opportunity to establish peacetime Intel functions.

The @USArmy would not set up a department for peacetime Intel tasks until a couple of decades after the Civil War, with the creation of a small "Division of Military Information” within the Adjutant General’s Office. (We will talk more about the AG Corps in a later thread.)

A few years after this, “the Army dispatched its first military attachés abroad to provide general information on worldwide military affairs.”

In 1903, the Army established its General Staff, and the Division of Military Information became the General Staff’s Second Section – we now call this the G2 in the Army, or J2 in Joint Staff environments, or other combinations of letters and the number 2 depending on service.

This shift to having a permanent Intelligence section in the General Staff was not exactly a smooth one. Between 1903 and WWI another “reorganization eliminated the intelligence function of the staff, and it took America’s entry into World War I to reverse the situation.”

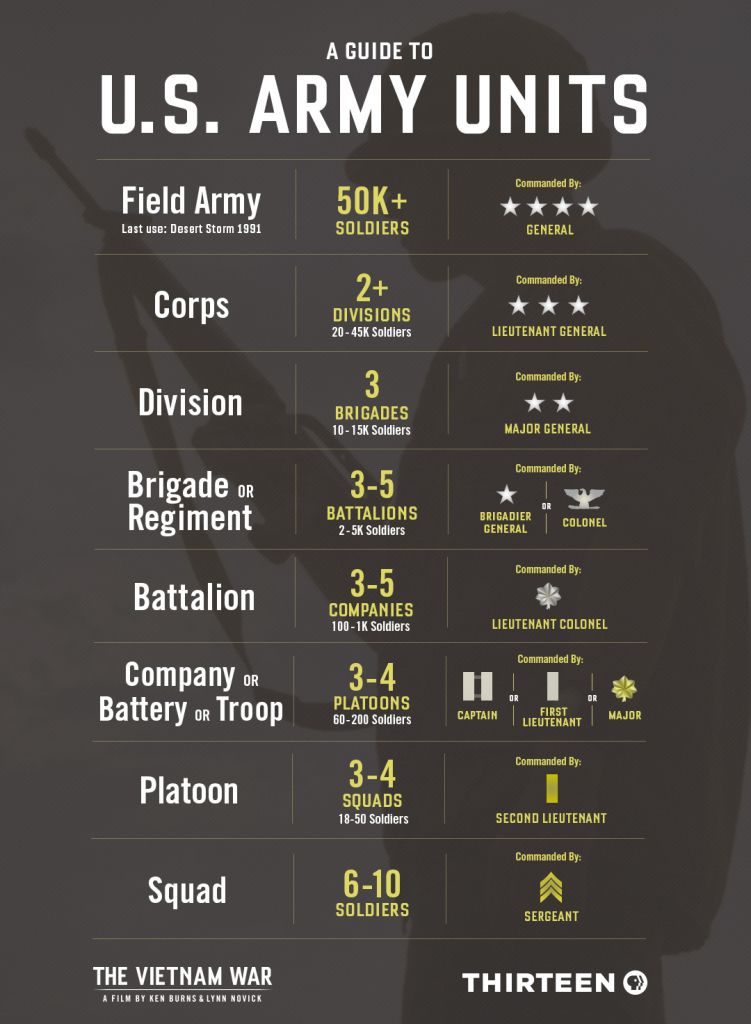

To prepare for WWI, the Army established an Intel section within the War Department’s General Staff and placed intelligence officers in all Army units from the battalion-level up.

“Military Intelligence expanded to become a ‘shield’ as well as a ‘sword,’ as the Army became heavily involved in counterintelligence.” 🛡️⚔️

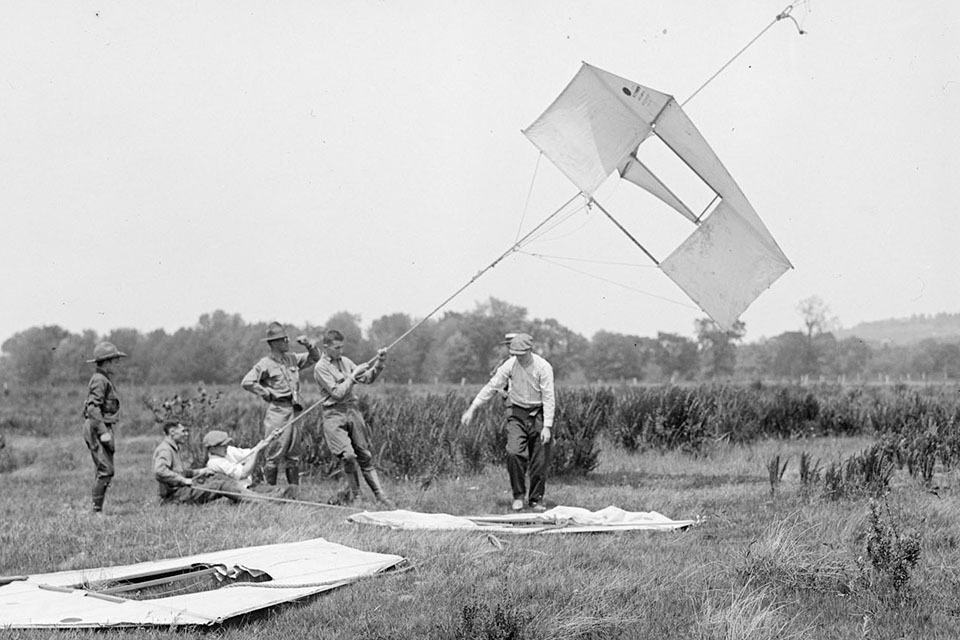

WWI “exposed the Army to a dazzling new array of technological enhancements to the collection process: aerial photography and reconnaissance, radio intercept, and optical and acoustical sensors used to detect aircraft and artillery.” (This photographer is British.)

This is a Perkins Man-Carrying Kite carrying US Signal Corps Lieutenant Kirk Booth (first pic). We didn’t actually use these kites in WWI but it’s cool and came up in an image search – this was taken at Camp Devens in Massachusetts.

The addition of new technology for intelligence collection meant that non-intel soldiers and officers could also contribute to the collection process. For example, the Signal Corps was involved in photography and radio intercept; aviators were involved in aerial reconnaissance.

The Armistice that stopped WWI brought on two decades of relative peace – the Interwar Years. During this time, the @USArmy was significantly reduced in size. But the Army continued to seek the right amount of Intelligence effort for its needs, regardless of its size.

One problem that the Army had to sort out first, however, was that of an established concept for Military Intelligence. In other words, defining what Military Intelligence is and what that part of the Army should do.

For a long time, the Military Intelligence components of the Army were used as a catch-all for anything information related, even if not exactly involved in intelligence cycles.

For example, during the Interwar Years, Military Intelligence personnel managed the Army’s public affairs programs. @USArmyCPA @JPC_1979 @OrlandonHoward @ForcePao @okayestPAO @18airbornecorps @kcmunoz_ @Bill_Leasure @TheMightyFred @MeganJantos @sunsetbelinsky

“Later they were tasked with conducting psychological warfare and writing the Army’s history.” @USArmyCMH @Erikhistorian @cmhexecdir @8thPSYOPgroup @GoArmyPSYOP @WTFIOGuy

It would actually take until after WWII for @USArmy Intelligence to be able to concentrate solely on Intel functions, which is important – during the time period we are focused on in this series, Army Intel Officers were being tasked with more than just Intel work.

In May of 1945, the Military Intelligence Division of the War Department acquired “an organization to establish intelligence priorities and requirements, missions that finally allowed it to put into practice all components of the modern Intelligence cycle.”

This included “determining requirements, collecting the appropriate information, processing the acquired data into finished Intelligence, and disseminating the results, a circular process that often generates a new set of requirements, initiating the cycle again.”

But before 1945, at the highest War Department levels, the Intelligence section was treated “more as a reference library.”

Without a perceived real-time threat facing the United States during the Interwar Period, many Intelligence Officers felt they had too little to do. We did not yet have a peacetime Intel concept.

Eisenhower would later comment: “I think that officers of ability in all our services shied away from the Intelligence Branch in the fear that they would be forming dimples in their knees by holding teacups in Buenos Aires or Timbuctoo.”

The Intelligence sections of the Army were also still fighting the widespread perception that “any officer could fulfill its functions.”

These attitudes would change in WWII. Under the National Defense Act of 1920, the Military Intelligence Division remained one of “four principal divisions within the Army Staff.”

Among MI duties were responsibility for attachés, supervision of military drawings and maps, writing regulations for tactical Intel personnel, liaison duties with other Intel agencies, approval of codes and ciphers, and planning of censorship operations.

The MI director position was set at the Brigadier General rank (1-star), and this position was one of four assistants to the Army Chief of Staff. But legislation only provided for 4 Brigadiers Generals on the Army’s General Staff so competition was high.

Military Intelligence also suffered from a shortage of funding during the Interwar Years, just as the rest of the Army did. By 1934, the MI section had only 20 officers and about 50 civilians.

Part of this weakening of the MI section was due to reorganization supported by General Pershing in the early 1920s. Pershing also insisted “that G-2 undertake public relations duties as it had done in the AEF.” This became a standard peacetime MI responsibility.

Many of the Military Intelligence Officers below the Corps level spent a significant amount of their time on Public Affairs duties during the Interwar Period.

This contributed to the MI branch becoming a sort of “dumping ground” for low-performing or limited officers and many came to regard “Intelligence assignments as detrimental to their military careers.” Thankfully, this changed significantly for WWII.

As with any skill, Intelligence capabilities are use-or-lose. Without regular engagement in Intel activities, this branch saw a “decline in its capabilities for Intelligence Collection.”

The primary means of collecting information for use in Intelligence, during this time period, was through the attaché system. (They weren’t really doing this 😂 attaché duties took precedence.)

George C. Marshall would later say of Army Intelligence during the Interwar Years that it was “little more than what a military attaché could learn… at a dinner, more or less, over the coffee cups.” @MelissasLibrary @georgecmarshall

The budget constraints of the Interwar Years saw many of the minor attaché posts abandoned, and without sufficient funding available, many of the remaining positions were “restricted to officers with private means of support, irrespective of their professional qualifications.”

The Interwar Years also “saw the rise of totalitarian governments and controlled and closed societies. Military attachés were allowed increasingly less freedom to collect useful Intelligence in precisely those countries that posed the most dangerous threat to American society.”

Although many of the MI components were not put to good use during the Interwar Years, one part of the Military Intelligence Division was made responsible for Intelligence training. But it was not seen as particularly valuable.

By 1931, the head of the MI training section said: “the state and extent of combat Intelligence training in the Army is not known to this branch, as it makes no inspections and receives no training reports.”

There was a Military Intelligence Officers Reserve Corps (MIORC), established in 1921. The idea was to have part-time Intel Officers trained and ready for use when the Army would eventually mobilize. The MIORC ranged between 400 and 800 officers (kind of a substantial range 👀).

The reality, however, is that many of the Reserve Officers were journalists and their experience in the G2 mostly related to Public Affairs. By the time we were mobilizing for WWII many of these Officers were “too old and too high ranking to fill the positions the Army required.”

“Perhaps the only lasting contribution of the MIORC was the adoption of the sphinx as its insignia, an action which had the effect of permanently associating this somewhat bizarre heraldic item with the field of Military Intelligence.”

This all sounds terrible – but there are positive things that happened during this time. For example, the Interwar Army worked on advancing technologies that would expand areas of Intelligence Collection, such as motor transport that would help enhance ground reconnaissance.

We will discuss scouts in a later thread but by 1931, the Experimental Mechanized Force existed, and scouts were starting to use armored cars and radios. (The first pic is actually Patton’s scout car from years later, the second is a scout car at @FortRiley )

The Signal Corps was working with thermal and electronic means of detecting aircraft and ships, and “by 1937 the Army had a pilot model of a mobile radar set.” This would prove vital in the development of early warning, especially with advances in aircraft. @Signal_School

Arguably, the greatest accomplishments of the MI Branch during the Interwar Period were in cryptology. MI would approve “cryptosystems for Army-wide use” and establish the regulations for using them. They were not working alone.

The Signal Corps was responsible for secure communications and the AG was responsible for printing and distributing codes. @Signal_School

We will continue talking about the Military Intelligence Branch on Saturday.

If you're just tuning in or you've missed any of the previous threads, you can find them all saved on this account under ⚡️Moments or with this direct link

twitter.com/i/events/13642…

If you're just tuning in or you've missed any of the previous threads, you can find them all saved on this account under ⚡️Moments or with this direct link

twitter.com/i/events/13642…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh