It's deceiving to look at long-term interest rates and think it was an easy, obvious trade. But even smart investors didn't know

Value investor Larry Tisch of Loews went all Berkshire and bought an insurer, Continental Casualty, to invest their portfolio float.

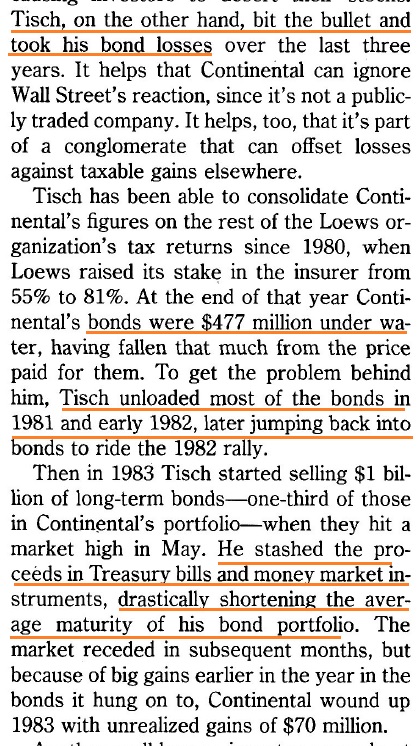

That portfolio had a big slug of duration bonds that were underwater. Larry took the loss when yields spiked and shortened the duration.

In 1984, when rates backed up again, it looked like a smart move.

In 1984, when rates backed up again, it looked like a smart move.

Buffett at least agreed: "Larry inherited a portfolio that could have been a financial Hiroshima. The other insurance giants all stared, transfixed as their bond portfolios slid into the sea. He resorted to action while the others resorted to prayer."

Meanwhile, Tisch was bullish. But it was a pretty tactical and somewhat convoluted view. Nothing about a secular bond bull.

And Tisch wasn't a bull for long. On year later, in 1985, "stumped about the future course of rates" he sold again.

The right move (to hold and perhaps lever up) wasn't obvious. So, he ended up trading around rather than locking in returns never to be seen again.

The right move (to hold and perhaps lever up) wasn't obvious. So, he ended up trading around rather than locking in returns never to be seen again.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh