I have a NEW PUBLICATION out, about productivity and much more. If there were one theme it is this: you can't restore UK productivity growth simply by going all-out on tech-rich, "high value" sectors.

Here is a thread 1/ instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/p…

Here is a thread 1/ instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/p…

Let's start with the Great Slowdown that began in 2008. Keep this in mind: had we kept to the trend of 1998-08 GDP growth, the economy in 2018 would have been £300bn+ larger.

Was this because the UK "put its eggs in all the wrong baskets?" NO! 2/

Was this because the UK "put its eggs in all the wrong baskets?" NO! 2/

It is a popular, miserabilist idea: Britain stopped making things, failed to get into new, high-tech industries, instead got into shopping, basic admin - the low value services. And hence we slipped off the growth train.

But the numbers are not there: 3/

But the numbers are not there: 3/

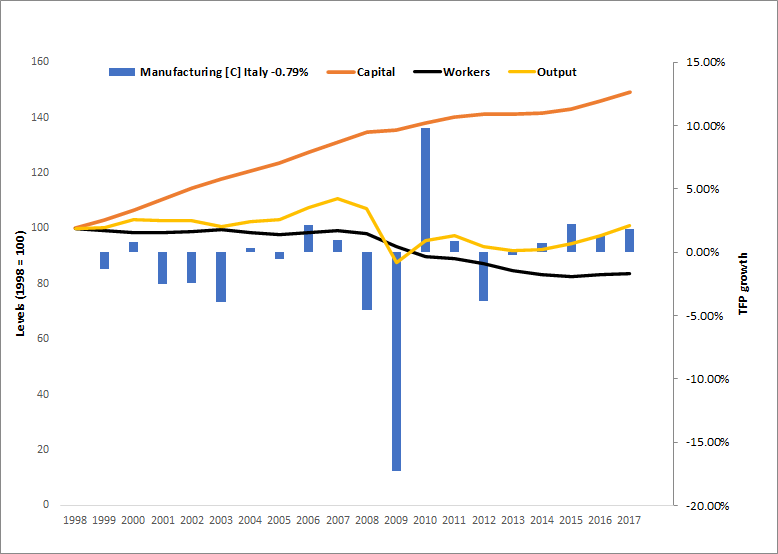

For a start, the major shift out of manufacturing - the higher-value sector decline that people most regret - took place in the *high*-growth period, up to 2008. The lower-growth decade after that saw relatively little movement 4/

I also carry out a thought-experiment similar to one @jeegarkakkad carried out a year back - swap our sectoral shape with Germany's, see what happens institute.global/policy/product…. And the result is: not much! 5/

Instead, as many others have pointed out (i.e. see this from @ChrisGiles_ and @gemmatetlow) the drag on growth was concentrated on a few sectors growing much more slowly than in the go-go years before, notably financial, professional services 6/

ft.com/content/a0cbe7…

ft.com/content/a0cbe7…

Alongside this, the slowdown in growth was fairly widespread. All sorts of sectors failed to grow as fast in the weak decade as the strong (see hard-to-read chart). This warns us to look for economy-wide factors in explaining it, in particular slow demand growth 7/

This also illustrates serious issues with the idea of splitting into sectors, and choosing which ones to make bigger, perhaps with R&D injections.

Economies. Are. Not. That. Simple.

The Chancellor is not like a factory owner picking which sector to sell more of. 8/

Economies. Are. Not. That. Simple.

The Chancellor is not like a factory owner picking which sector to sell more of. 8/

I have MANY issues with assuming bigger sector= better for UK.

Industries serve each other, compete for common resources, their size is about *demand* - the most ignored factor in productivity discussions.

And being smaller is not necessarily bad! Favourite example: energy 9/

Industries serve each other, compete for common resources, their size is about *demand* - the most ignored factor in productivity discussions.

And being smaller is not necessarily bad! Favourite example: energy 9/

My particular bugbear: the simplistic assumption that putting in more tech leads to more growth and high value jobs. All of these sectors saw technological/structural change - and the effect in terms of jobs (X axis) and productivity (Y axis) is ... variable... 10/

... which is why I criticize the Public Accounts Committee for demanding that the Industrial Strategy Challenge Funds show their impact on jobs and growth. No, it is not that simple 11/

So I have criticized a lot of wrongness in this report. What DO I think should be done with productivity? Well, recognise that you can't do it all with the standard sexy targets of industrial policy.... 12/

... and acknowledge (as @HetanShah recently wrote) that lower-value jobs can play a really significant part. And in fact HAVE played a part - the significant rises in productivity in retail and admin, for example, given rocket-boosters under Covid 13/

but the most radical thought, saved for last: stop ignoring economic demand! For decades UK governments have regarded this as heresy - but can it really be a coincidence that the productivity crisis emerged just as demand growth took a whack in the solar-plexus ? 14/

As well as luminaries like Janet Yellen who have called for a "high pressure economy" - check out @MESandbu book, The Economics of Belonging, which lists mechanisms by which too-weak demand can hurt productivity widely 15/

Or the smart point made by @jdportes in this piece about levelling up. London's restauranteurs are not necessarily smarter than their poorer peers elsewhere - they just get more business 16/

bylinetimes.com/2021/05/11/wha…

bylinetimes.com/2021/05/11/wha…

Thanks for making it this far. It is a better read than its dry subject matter would suggest! If you think the government shouldn't get away with thinking its R&D spending is the only productivity policy it needs, this is the report for you! 17/17

instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/…

instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh