This week I’ve been working remotely from Matalascañas, a beach in Spain where my parents bought a house in the 80’s. Growing up in Miami meant my siblings and I were constantly exposed to Spanglish, but my folks — Cuban exiles — were determined that we learn proper Castilian.

They scoured the Mediterranean coast looking for an English-free spot to spend the Summers, but in town after town they found drunk Brits. But on one trip they stumbled upon this Atlantic beach, an for Seville’s working class with not a single foreigner in sight.

Located nearly an hour south of Seville and accessible only via bad country roads, Matalascañas was a barely developed backwater back then, just a few buildings on a stretch of beach surrounded by Doñana National Park (home to the ever-endangered Iberian lynx).

The place’s other claim to fame (if one can call it that) is “la piedra,” a.k.a. the Torre de la Higuera, an ancient building that once served as a watchtower against pirates, but which tumbled into the sea the day the Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755 shook most of southern Spain.

Like much of the Spanish coast, over the course of the past 30 years Matalascañas has been subjected to a haphazard building boom, with an endless array of buildings and chalets packed into the small stretch, which is forcibly limited by the borders of the national park.

If one was feeling generous one could call the overall architectural style “eclectic,” but it’s evidently more due to the lack of any serious urban planning philosophy than to the hard work of any municipal building commission.

Matalascañas’ look isn’t determined here, but rather in Almonte, a village located some 30 miles inland that also controls the Hermitage of El Rocío (a major pilgrimage site in the area).

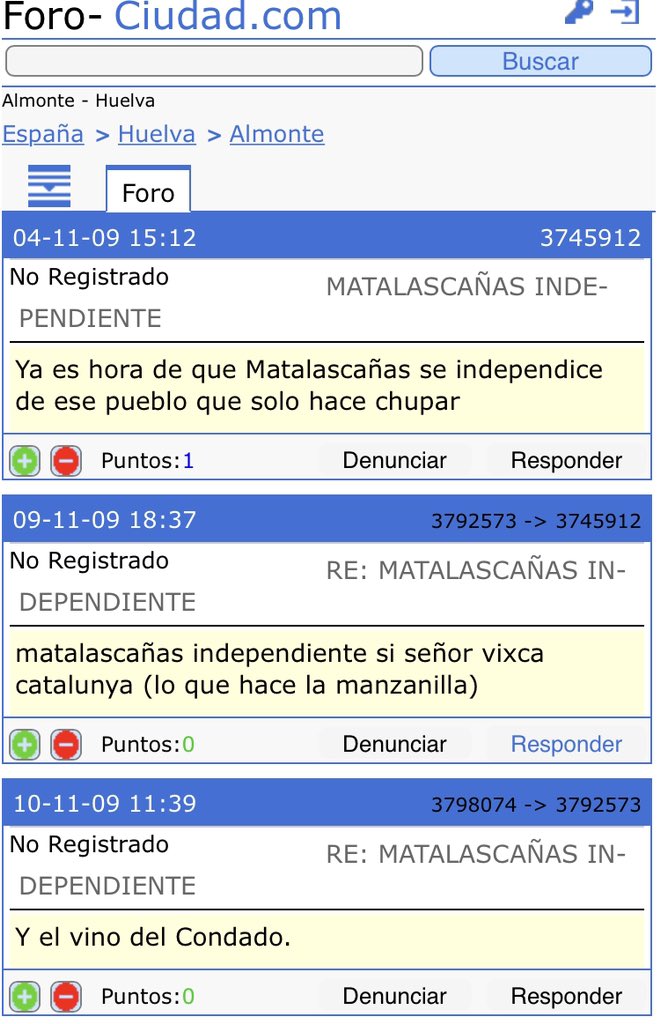

For years there has been an active effort to have Matalascañas declare it’s independence from Almonte, with proponents arguing that the interior village is making easy cash off the beach town without actually investing in the coastal community.

Coincidentally or not, at some point Almonte apparently decided to show that it *did* make investments in Matalascañas by basically flooding the main road that extends across the town’s border with really questionable public “art” mounted on roundabouts.

There are more examples posed in public “parks.” One can agree to disagree re: the garishness of the “art,” but the parks themselves have obviously been designed with zero interest in users, hopelessly exposed to the Andalusian sun with not a single water fountain in sight.

Bonus:

— A monument to milk canisters?

— A rather sad shooting star

— Selkies or something

— A fort on a roundabout adorned with cannon of unknown provenance (to my knowledge, no battles have been fought here, as there was basically nothing here prior to 1960)

— A monument to milk canisters?

— A rather sad shooting star

— Selkies or something

— A fort on a roundabout adorned with cannon of unknown provenance (to my knowledge, no battles have been fought here, as there was basically nothing here prior to 1960)

I’m not sure if Almonte’s rather ham-fisted effort has had any impact on residents, but with less than 2,500 citizens, Matalascañas is also unlikely to ever have the votes to secede. That doesn’t mean that the debate isn’t lively, though (as these outdated screenshots show).

Anyway, this is a very random place to come back to every so often to hear people refer to you as “tss, ‘illó” and see brutalist blocks adorned with ceramic portraits of crying virgins, and eat good pescaíto frito while tirelessly providing exhaustive energy and climate coverage.

Indeed, in case anyone (read: editor) should think it’s all fun and games in Andalucía, while here I’ve been anchoring the section’s energy and climate newsletter and personally experiencing the record-breaking Spanish heatwave that we’ve been covering...

elpais.com/espana/2021-08…

elpais.com/espana/2021-08…

...But the real point was to see my little brother, who I hadn’t seen since January 2018, and my sister, who I last saw in the fall of 2019. And so that’s been pretty great as well after this very long pandemic. So hurrah for that.

Bonus track:

Fun addendum as I head off from Matalascañas: when we bought our house it faced a vast lot of oceanfront sand dunes that used to be a problematic breeding spot for mosquitoes. In the late 90’s a local business man bought it and built a North African-themed vacation village there.

But he donated part of the land he bought for the Catholic Church and, keeping with the theme of the neighboring development, upon that lot a rather bewildering church was built in the exact look and layout of a mosque.

I’m not sure if it’s still the case, but during the first years it operated the priest apparently lived in the minaret, and my late mother swore that, glancing at the tower windows from our terrace, she had seen him changing clothes after mass on more than one evening.

I can’t recall any debate as to the religious sensitivity (or lack thereof) that goes into conscientiously building a Catholic Church that looks like a mosque, but given that the cathedrals in both Seville and Córdoba are former mosques, it’s somewhat in keeping with the style?

Whatever the motivation, the open-air services in the courtyard meant that for years and years locals could comfortably sunbathe on their terraces while simultaneously hearing mass.

(Amen.)

(Amen.)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh