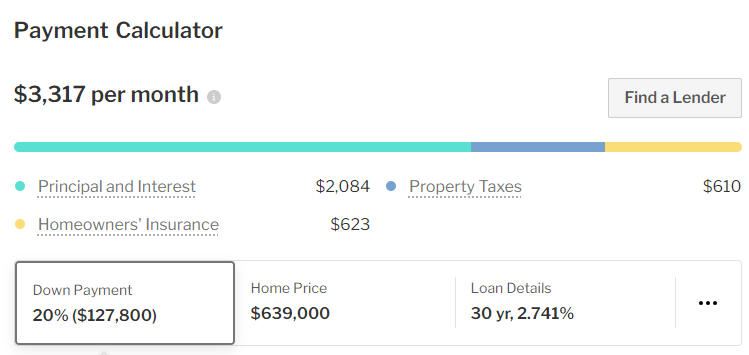

It's overlooked how much property values are impacted by property taxes and homeowner's insurance rates. For example, a $600k house in Houston or $640k house in Miami has roughly the same monthly cost (assuming 20% down payment) as a $735k home in Los Angeles.

Utilities also probably play a meaningful role, though I don't know how the costs compare between cities. I assume Houston has the highest utility bills and LA the lowest (at least within 5-10 miles of the coast), but could be wrong.

I'd always been aware of this with respect to property tax rates, but this @CityObs article got me thinking about the insurance side of things. Look at that annual premium in the Miami metro! Almost $1,000 per month! cityobservatory.org/insurance-and-…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh