Now let's talk about the "TBA" market. It is one of the most important features of MBS and it explains why the market is so liquid.

For those that have a mortgage on your house, you may remember that you "locked in" your rate at some point, but it was a few weeks before you actually settled on the house (or refi). Why was your bank willing to take all that interest risk between lock-in and settlement?

The answer is: they didn't. They pre-sold your loan before they actually had it in hand. The TBA (or "to be announced) is how this is possible.

TBA is basically like a futures contract for mortgages. A bank can "sell" $1mm of TBA MBS for delivery multiple months into the future and lock in the price that they'll get for your loan. This isn't very different from a farmer locking in the price of wheat by using futures.

TBA is so central to MBS that it dictates how the whole market works. E.g., TBA is organized by coupon and maturity. MBS coupons only exist in 0.5% increments. I.e., there is a Fannie Mae 2% and a 2.5% MBS, but not a 2.25%. Why? Because it makes it easier for TBA trading.

There are active TBA markets for 30-year and 15-year MBS, although volume in 30-year is substantially greater. MBS exist for 20 and 10-year mortgages as well as ARMs, but there is no TBA market for these and thus these MBS are far less liquid.

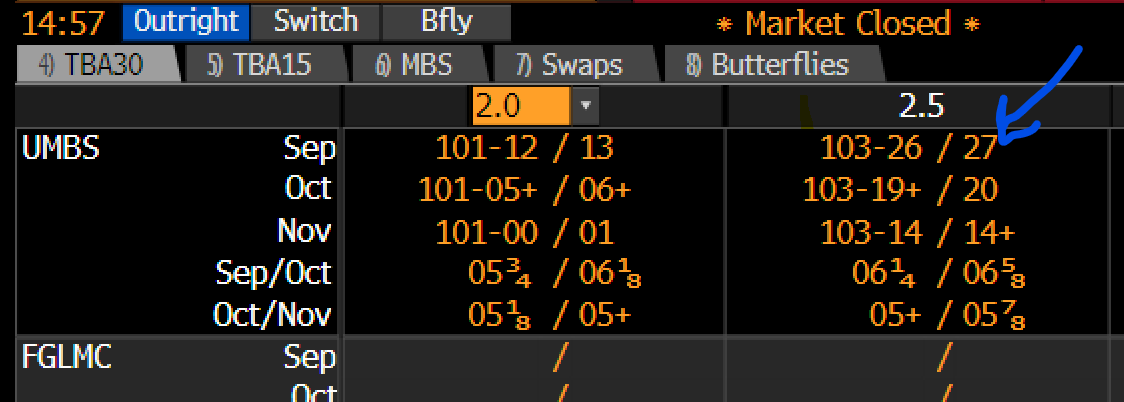

You can see the current TBA market on BB by just hitting TBA<GO>. The page I prefer is TBPF which allows you to see some other details like performance vs. hedges.

TBA contracts settle on a certain day each month, called the "good day." Generally even if you are trading a real MBS bond, your counter-party will prefer to settle on good day, since it will correspond with their hedge.

TBA is also why trading MBS with long settlements is no big deal. There is very active TBA trading out 3 months, so it is easy to trade either TBA or cash bonds for settlement all the way to "good day" in October or November.

Now like all bonds, you don't start accruing interest until the bond settles. Ergo waiting multiple months before settlement is disadvantageous to the buyer of the bond. They have locked in a price but aren't earning any carry.

This problem is solved via "drops"

This problem is solved via "drops"

The drop is the difference between the price to settle in one month vs. the next month. Basically if a buyer is going to wait an extra month to start earning carry, they get a discount on the price to compensate.

Below you see the current px for Sept, Oct and Nov 2% TBA.

Below you see the current px for Sept, Oct and Nov 2% TBA.

The drops are indicated by "Sep/Oct" and "Oct/Nov", which is about 5 ticks or 5/32 of price (yes, MBS still trade in fractions!)

The drop fluctuates a lot having to do with supply/demand as well as expected refi rates. It is something that MBS desks trade actively.

The drop fluctuates a lot having to do with supply/demand as well as expected refi rates. It is something that MBS desks trade actively.

On TBA settlement day, if you are still short the contract you have to deliver MBS that meet the criteria. If the contract was 2% 30yr, you basically have to deliver a bond with more than 15yrs to maturity and a 2% coupon. There are some other details but they aren't important.

Similar to other contracts, there is an implied "cheapest to deliver" concept here, which MBS guys often call "worst to deliver." Whoever is short a TBA will deliver the least attractive MBS they can get their hands on. More on what makes some bonds better than others later.

Regardless, most contracts are never delivered, they are just closed out and/or rolled to the next month. For example, I use TBA to get passive exposure to certain parts of the MBS market. I have no intention of taking delivery.

Long before delivery day in Sept, I'm going to sell that contract and buy an October contract. This is call "rolling" and is very similar to what happens in other futures markets for people who want consistent long or short exposure.

OK let's get back to the originator. Remember that MBS only exist in 0.5% coupon increments, but real borrower rates are usually in 0.125% increments. So the originator has loans that are at 2.625%, 2.75%, 2.875%, etc. What kind of pool do these wind up in?

This is actually up to the originator. They can take a 2.875% loan and sell it into a 2% MBS, keeping 0.875% as a servicing fee. OR they could sell it into a 2.5% MBS and keep just 0.375%!

Since the price of the 2.5% MBS is higher (about 103.875 vs. 101.375 for 2%) it comes down to whether they want to collect more up front when selling the bond or if they want to collect a higher servicing fee over time.

For some history, it used to be that 0.5% was a good rule of thumb for servicing fees, but today that's much higher. Right now the average 30-year 2% MBS has a 0.85% average servicing fee. IOW, the average borrower actually faces a 2.85% rate.

On BB, you can analyze a "generic" MBS by using the ticker "FNCL" or "FGLMC" and a coupon rate. So FNCL 2 Mtge <GO> will bring up a generic 2% Fannie Mae MBS for analysis. The stats on the DES page are the average for that coupon cohort. I'll hit what these stats are in a moment.

OK enough technical stuff. Let's talk how you analyze MBS. The first thing to note is that US mortgages are prepayable anytime without penalty. They also aren't assumable, so if you move, you have to pay off your mortgage.

As a result, virtually all MBS analysis is about how quickly the underlying borrowers will repay their mortgages. The biggest factor is obviously refinancing due to falling rates. The second biggest is "turnover" or people selling their house. Then comes defaults.

There is some effect to "curtailment" or people just paying a little extra over time. That's minor and rarely worth worrying about unless you have a deeply factored pool.

OK so in an earlier installment of BBB, your regular professor @EffMktHype mentioned callable bonds.

https://twitter.com/EffMktHype/status/1425747733537648642

@EffMktHype Go ahead and read that section if you aren't familiar with callability in bonds. Because optionality is kind of a doozy with MBS.

@EffMktHype With a normal bond, you basically have one decision maker (the issuer) reacting to one incentive (can they reissue new bonds at a lower yield?). MBS are quite different on a number of fronts.

First, MBS are callable immediately upon issuance. Most bonds have some period of time before the bond is callable. Second, every borrower within the pool is making their own decision to refinance. So there are dozens to thousands of decision makers.

Third, each of those decision makers aren't facing the same circumstances as each other. Sure their current mtg rate is similar, but their lives are not. Here's where it gets really interesting.

Let's say there are two borrowers. @EffMktHype has a $900,000 mortgage with a 3.375% rate. @tdgraff has a $100,000 mortgage with a 3.625% rate. Let's say that both could get a new mortgage at 2.75%. The fee for doing the refi is $3k.

Even though @EffMktHype has a lower rate than @tdgraff, he saves way more money per mo. on the refi (~$300 vs. only about $50). So it only takes @EffMktHype about 10 months to make back the refi fee, whereas it would take me about 63 months.

Here we can see that while both could borrow at the same rate, they have very different actual refi incentive. This is just one of dozens of ways borrowers can face different incentives. From this is born the real fun of MBS: prepayment analysis.

First some quick definitions. How quickly principal is repaid is called "speeds" in MBS land, and there are two main measures. The OG is called Conditional Prepayment Rate or CPR.

CPR is basically the pct of the loan that would pay off in a year if payments kept coming in at the current pace. So if you saw a 3mo CPR of 12, it means 12% of the loan would pay off if the pace of the last 3mo continued for 12.

The other is PSA. The PSA assumes that a MBS starts at 0CPR in month 1, increases by 0.2CPR every month until it reaches 6CPR and remains there. The PSA is quoted as a percentage of this basic model. So 150PSA in month 31 = 9CPR (6CPR * 150%)

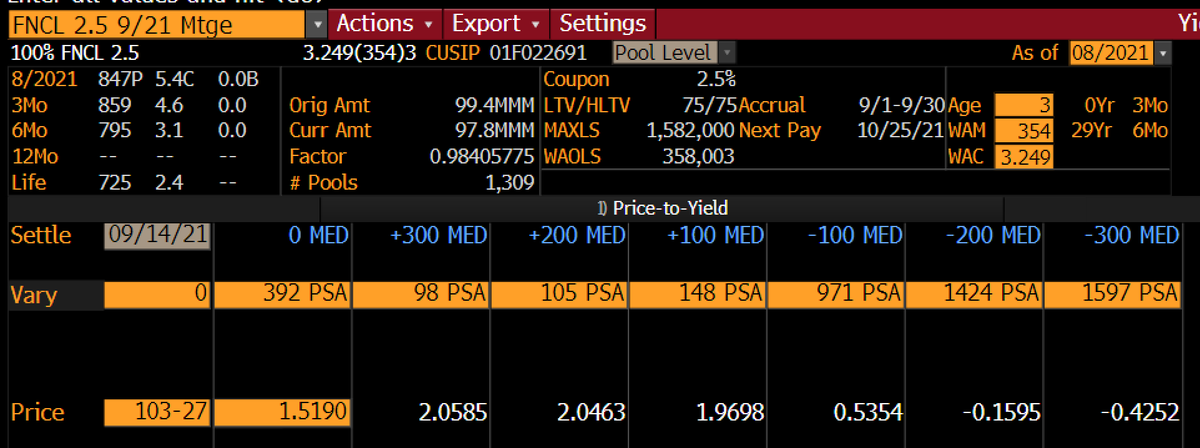

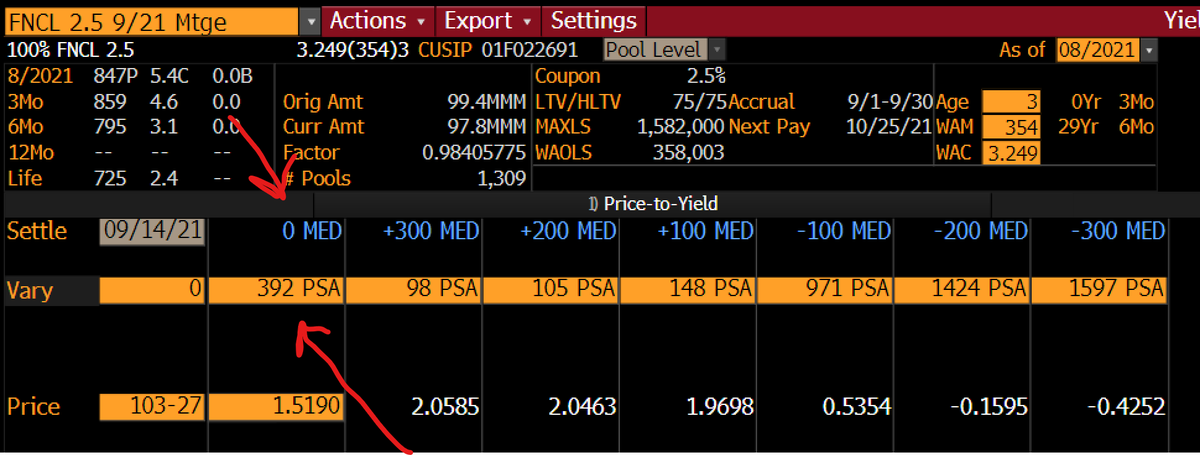

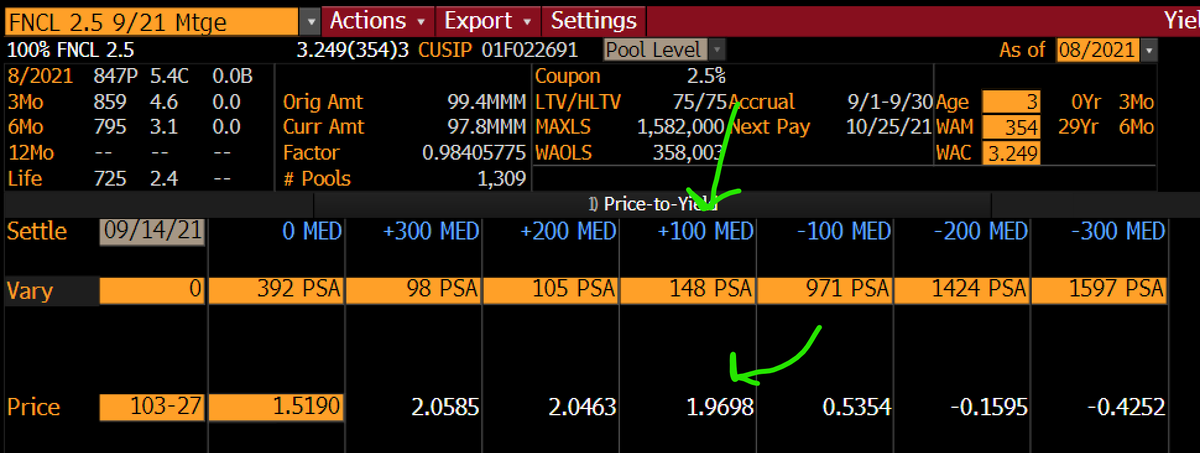

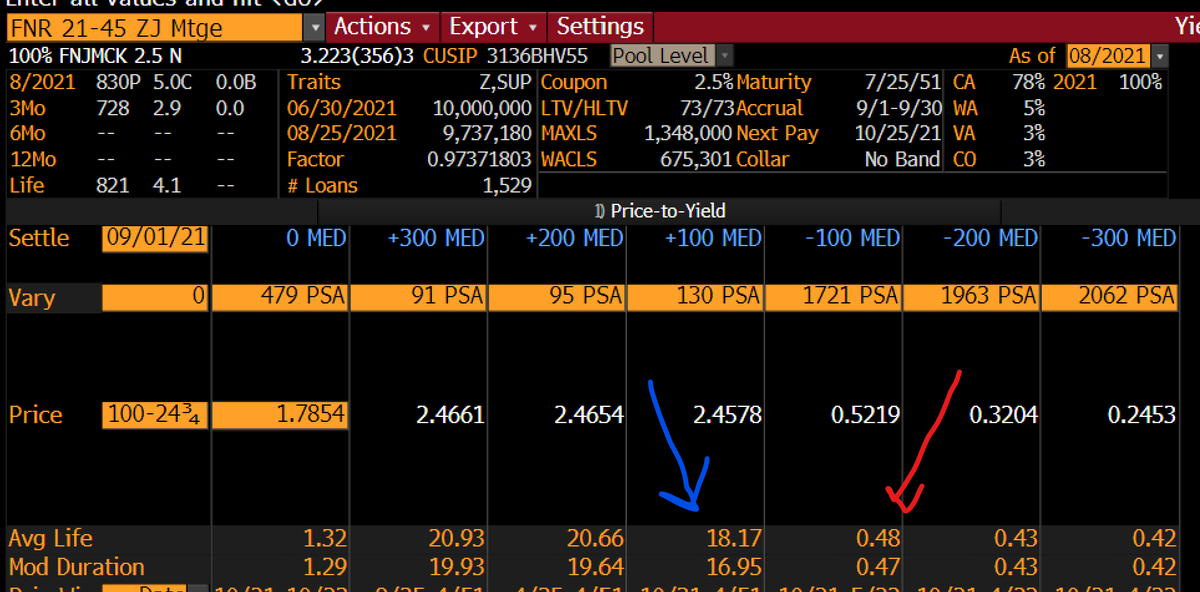

OK so let's look at how important these speeds can be to your bond's yield. Below is the YT function on BB for a generic 2.5% MBS. I'll walk through what's here.

Toward the middle of the page, you see a "Price-to-Yield" header and then a series of "0 MED" "+300 MED" etc. Each of these are BB's estimate of prepayment speeds given a certain change in mtg rates. The current (0 MED) is 392PSA. That gives the bond a yield of 1.519%

However we see if the bond were to pay slower, say 148PSA (BB's estimate for speeds given 100bps rise in rates) the yield jumps all the way to 1.97%! Woot!

Here we have two important things to note. First, let's say general yields did rise by 100bps. This is still a bond with duration, therefore it will lose money because of price decline.

However, it won't lose as much as its duration implies, all else being equal. This is because the value of the embedded option declines. Remember w/ a callable bond, the investor has shorted a call to the borrower. When rates rise, the call gets further from its strike.

The second interesting thing here is what if you could get the slower prepayment speed *without rates changing*. In other words, just get extra yield without having to suffer through the whole annoying price decline bit.

That's where doing prepayment analysis really benefits your performance. If I can buy a pool that pays slower than generics, I earn that extra yield. If I could buy that pool for the same price as the generics, I could even use the TBA market to hedge!

Alas, life isn't that easy. Take our example from earlier where one borrower had a very low balance on the mortgage and thus would be much slower to refinance. Everyone knows this, and so they demand a higher price for a mortgage full of such loans.

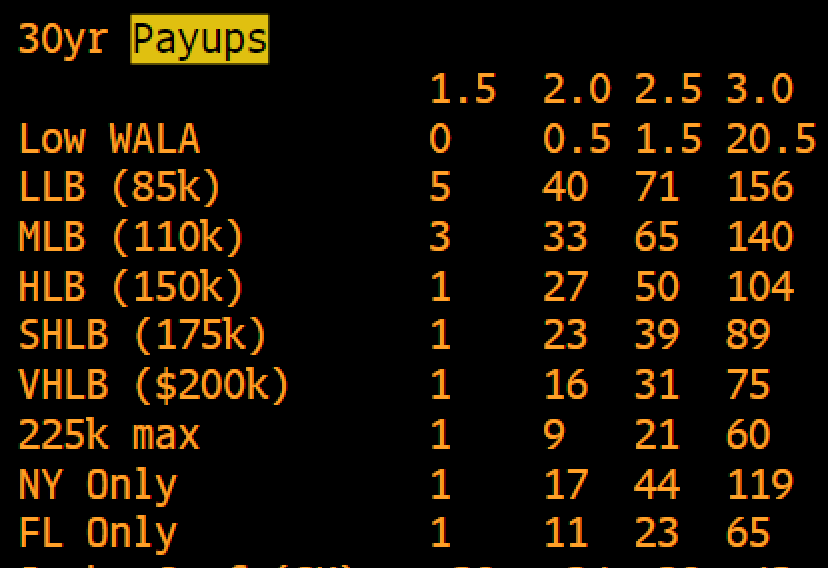

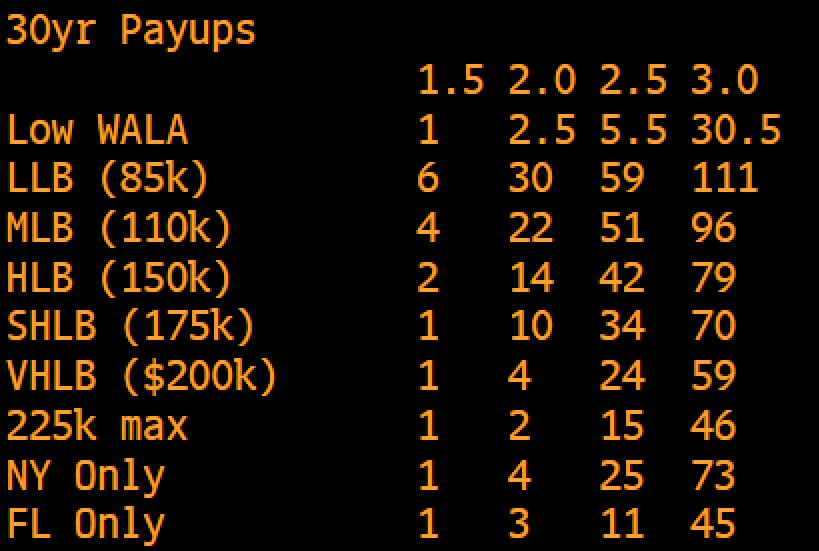

This is called a "payup" and it is quoted in 32's vs. TBA. Below is one dealers estimate of generic payups for different types of pools. Here "LLB" means a pool where the largest loan is only $85,000. The payup for as FN 2.5% is 71/32.

So if TBA 2.5% is $103 27/32 on the ask side for Sept (see below) and I payup 71/32, that comes to $106 2/32 all in. This system is more convenient vs. classic yield spread because it avoids dealing with differing prepayment models and/or settlement preferences.

Pools where 100% of the items within it have some special characteristic are called "stip" pools (for stipulated). Note that it has to be 100%. If there were to be a pool where half of the loans were LLB but the other half were just average, no one would pay up for that.

Of course, those kinds of pools don't really exist. Going back to the originator, they aren't going to mix a bunch of generic loans with another set of loans that Wall Street will pay up for. They aren't in the business of throwing away money.

Quick aside for how I personally approach pass-throughs before moving on to CMOs. Big payup pools are risky. Take our LLB example, which currently is around +71. What happens if general interest rates rise? Suddenly that prepayment protection isn't worth as much.

On 3/31, here's that same dealer's estimate for payups. When rates were a bit higher, the LLB payup was 12/32 lower. So in effect, this bond has a higher duration that stated, because rising rates will cause both the base price AND the payup to decline.

Now it is true that you can't find a pool with some LLB and some average loan balance, but you can find "mutt" pools that have various attractive characteristics at very low payups. That's especially true if you look during times when rates have recently risen.

I try to look for loans that are newer (people usually don't refi or move within the first few months), have some more favorable geographies (some places pay slower), more favorable servicers (some market more aggressively), and some other details that help out.

If you can buy these kinds of pools with very little payup, your downside vs. TBA is capped. IOW, a pool can't trade less than the TBA price (assuming it is deliverable) since you could always just deliver it!

So if I only pay 4/32 for a pool, my relative downside is just those 4 ticks. I don't have to be all that right about my prepay work to outpeform.

Before we go any further, let's talk about convexity. Amazingly, this GIF exists.

Technically, the term is the second derivative of change in price IRT to change in yield. I prefer to explain it in plainer English, esp IRT MBS, because it not only makes more sense, it is more applicable.

A bond is negatively convex anytime its price underperforms what you'd expect by simply multiplying the delta of rates by its duration.

In the case of MBS, this is basically *always* the case when rates fall. The bond doesn't appreciate bc it is assumed everyone will refi.

In the case of MBS, this is basically *always* the case when rates fall. The bond doesn't appreciate bc it is assumed everyone will refi.

Ostensibly a bond with call protection, like our LLB bond, should have better convexity. In fact, your MBS salesperson will tell you this. It doesn't get refi'ed as quickly!

But I already showed you how it can underperform when rates rise, because the stip payup falls.

But I already showed you how it can underperform when rates rise, because the stip payup falls.

But wait, it gets worse. The LLB borrower doesn't refi as quickly at first, but eventually rates fall enough that it doesn't matter. He refis too. Now your payup was worthless. Ergo there's only this narrow range where the payup benefits you.

When I think about pools, I lump all of this into negative convexity in my head. Again, it doesn't fit neatly into the mathematical definition, but I think it is a cleaner way to think about the concept.

Last points on negative convexity. It is the main reason why MBS yield so much compared to other product. The stated yield on the MBS index is 1.70%, all govt gtd!

Related, this is a big reason buy-and-hold investors love this space. Banks, insurance companies, etc.

Related, this is a big reason buy-and-hold investors love this space. Banks, insurance companies, etc.

If you can just collect book yield, and especially if the light capital charges that Agency MBS have benefit you, MBS are a great space.

For total return investors like me, this is a source of inefficiency. Buy stuff that has a good TR profile but not great book yield.

For total return investors like me, this is a source of inefficiency. Buy stuff that has a good TR profile but not great book yield.

Speaking of banks and inefficiencies... let's talk CMOs.

Again, I'm only going to focus on Agency-backed CMOs. If @EffMktHype does a bit on ABS (or if he wants another guest lecture) the non-agency types should be covered there.

@EffMktHype OK so say you are Wall Street. You've got this huge MBS market with tons of flow. And buyers love AAA-rates bonds. Should be a gold mine!

Here's the problem. So many bond buyers want certainty around when their principal will be returned. How can you get these investors to buy?

Here's the problem. So many bond buyers want certainty around when their principal will be returned. How can you get these investors to buy?

In the 80's they came up with a solution. You take set of pools and put them in a trust. Then you sell new bonds based on the cash flow coming out of that trust. Here's a simple example with what's called a "sequential" CMO.

Say you sell three bonds off the original pool. The first bond gets every dollar of principal until it is paid off. Then the second, then the third. Assume each is exactly 1/3 of the original pool amount.

The speed of repayment for the first bond would be 3x as fast, because it is getting 100% of the principal but on only 1/3 of the base. So if the original pools were going to remain outstanding for 6 years, maybe this front sequential is only 2 years!

And now take the last pay of this 3-part sequential. It probably has a very long average life, but certain buyers want that. Maybe you are an insurance company matching liabilities. This back sequential might be just what you want!

For Wall Street CMOs are an arbitrage. Can you find someone who will pay up for the short-term certainty, someone else who will pay up to match a long liability, etc. such that the total paid for the pieces is more than it costs to acquire the pools in the first place?

Now as a wise MBS trader once told me early in my career, prepayment risk can neither be created nor destroyed. Whatever prepayment risk is lowered for someone within the structure, it has to be higher for someone else.

Wall Street found there were always more buyers of the short bonds than the long bonds. So they needed to make more short bonds. But who could take the extra prepayment risk? Enter the PAC, or "planned amortization class."

A PAC tranche of a CMO will payoff in a narrow window. For example, you would get no principal until month 24, then the bond would pay off entirely by month 30. It kind of simulates a normal bond. If you are thinking "why not just buy a normal bond?" you get extra credit.

(of course, the answer is there's better sales credit in the PAC CMO so your friendly Citigroup sales person is going to badger you about it)

In order for the PAC to work, there needs to be some part of the structure to take any "extra" prepayments that would force principal too early, but also someone to cushion the PAC if prepayments come in too slowly. These are called "support tranches."

I'm not going to go into the math of how supports work, but presume they are extremely volatile but at times are cheaper than they "should" be because Wall Street bribes people to take them to make the rest of their goldmine CMO structure work. But buyer be ware.

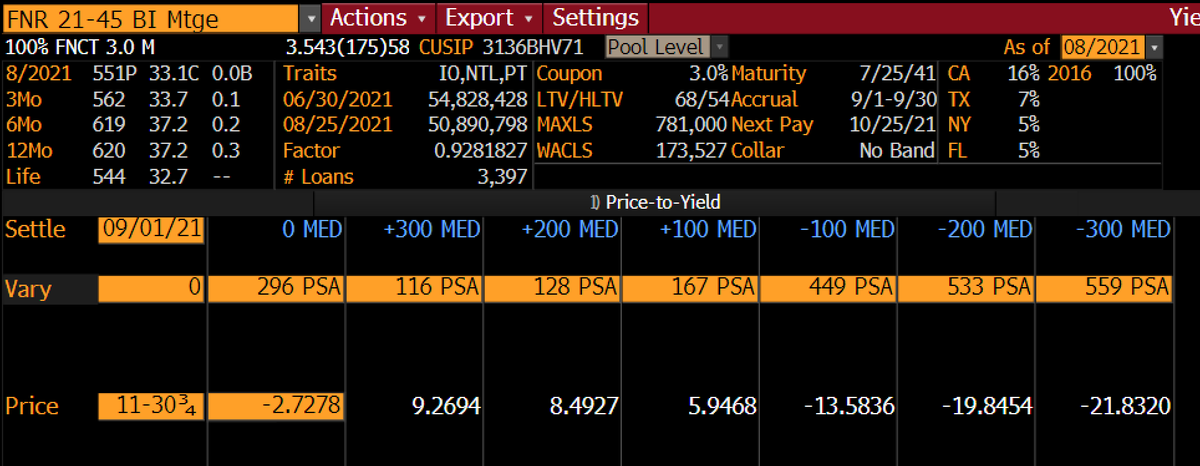

Here's a quick example of what life in a support tranche looks like. Notice how wildly the average life fluctuates given changes in yield.

OK this solves part of the problem of shuffling prepayment risk, but not all of it. The CMO is a closed loop. Every dollar that comes in has to go out, and there is no one who can contribute the pot. So if the supports get exhausted, the PAC can't hold up.

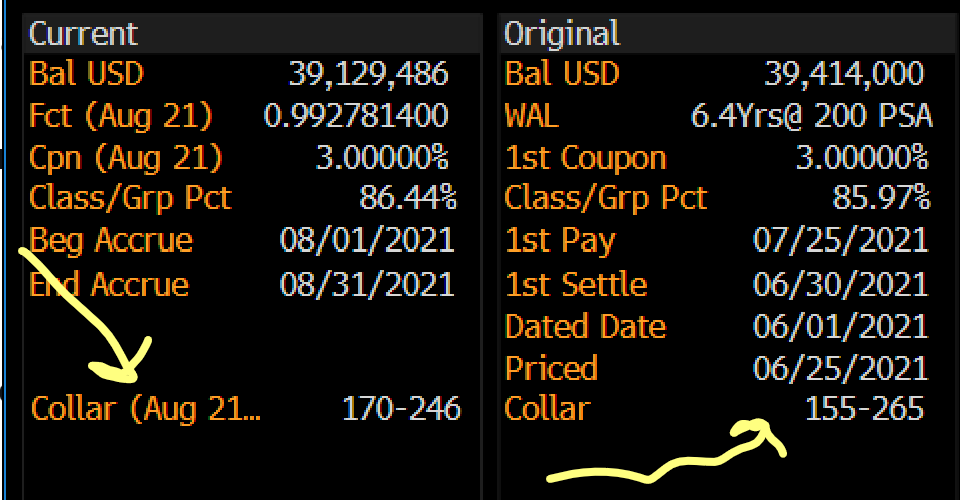

The speed at which this might happen is disclosed at the outset. This is called the "band" or the "collar." Here's an example where this bond was originally marketed to be a ~6.4yr avg life as long as the PSA was between 155-265. If it persists outside than band, it will "bust"

Things get real hairy if speeds go really fast for a while and then slowdown. Say speeds run at 600PSA for a while then slow to 100. That can turn this bond into a "extend-o-matic", where it goes from having an extremely short life to a very long one due to lack of supports.

There's one special type of CMO worth mentioning, and those are interest-only strips, or just IOs. These are CMOs that only pay interest, no principal. Eventually they are worthless. It is a matter of how much interest you collect before that happens.

Obviously the slower the prepayments in the underlying pools, the more interest gets collected in the trust and the better the IO will perform.

Here's an example of a stripped coupon off 3% MBS. Notice the dollar price is just shy of $12. Notice also that the yield is *negative* at base speeds!

This results in these bonds having a funny property: they have a negative duration. Meaning, if interest rates rise, you get more coupon payments. Because there's no principal to discount, rising rates is all good for these bonds.

OK we're almost done. Congrats for making it this far.

A couple thoughts on the kinds of markets where MBS tend to outperform other types of high-quality bonds. IOW, why would someone like me who runs Barc Agg strategies overweight or underweight MBS?

First, MBS have great carry as I mentioned before. So if you expect rates to be very range-bound, MBS can before very well. It is like writing covered calls on a stock that doesn't move.

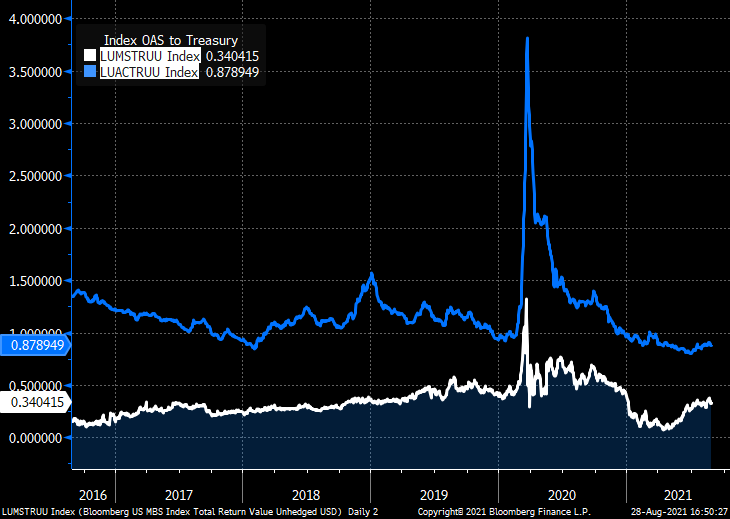

Second, MBS spreads (white) tend to be very stable compared to corporates (blue). They also aren't very correlated. If you think credit spreads are vulnerable, MBS can be a defensive position. OTOH, if credit spreads tighten, MBS def won't keep up.

MBS are also sensitive to interest rate volatility, for exactly the same reason that calls/puts on stocks are sensitive to the VIX. The MOVE index is something of a similar barometer. If volatility declines, MBS tend to outperform.

Alright class, that's it. Hope you enjoyed it. Feel free to throw questions my way. And please thank @EffMktHype for letting me hijack his class.

As an appendix, here are some other terms MBS traders use that I haven't mentioned yet...

As an appendix, here are some other terms MBS traders use that I haven't mentioned yet...

@EffMktHype "Orig" and "Curr": We often look at the original of some loan stat vs. its current. Since the borrowers aren't homogenous, certain stats can change over time in meaningful ways. Sometimes abbreviated as just O and C, so "OLTV" is original loan-to-value.

@EffMktHype Speaking of which: LTV is loan-to-value. Basically the inverse of how much equity the borrower has in the house. 80 is standard. High LTV pools are sometimes sold as call protection, but note that someone w/ 95 OLTV can get a better rate if price appreciation gets him to 80.

FICO is the borrower's credit score. Similar to LTV, this isn't a stip I like to buy. It only takes about a year for a low FICO borrower to "cure" if they stay on time, and then they can refi into a lower rate even if general rates haven't fallen.

With both LTV and FICO, the point is that the GSE charges a higher guarantee fee, so the mortgage bank is going to charge a higher rate. If they "cure" these problems they will prepay quicker than average.

Geo's are the term for what states the loan is from. 100% in one state can be a stip, especially NY, where the fees for refinancing are especially high. Which states pay faster or slower sometimes has a lot to do with where home prices have recently been rising.

HPA = home price appreciation. The more prices rise the easier cash-outs are, the easier it is to move, LTVs get better, all no bueno for MBS investors.

WAC = weighted average coupon. This is the underlying mortgage rate faced by the borrowers.

WALA = weighted average loan age. How many months the loans have been outstanding (not the MBS, the loans).

WAL = weighted average life. This is how long each dollar of principal will be outstanding on average. Basically how long it will take for 1/2 of your bond to pay off.

WAL = weighted average life. This is how long each dollar of principal will be outstanding on average. Basically how long it will take for 1/2 of your bond to pay off.

WARM = weighted average remaining mortgage. Also quoted in months.

Day delay: this is how long between the servicer getting the payment from the borrower and them passing it through to the bond. Its about 1 1/2 months. Keep this in mind when looking at speeds. This month's speeds reflect payments made two months ago.

"Collateral" and "structure": terms CMO guys use for passthroughs (collateral) and CMOs (structure).

TPO: Third-party origination. Basically this is the pct of the loan that non-bank brokers originated. Might be a sign that the borrowers will pay faster since the brokers tend to market refis aggressively.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh