The discussion of #SouthSudan oil often focuses on domestic mismanagement. But yesterday’s @CrisisGroup report also shows that it’s an international undertaking. This means there are lots of companies that can help nudge it towards more transparency and accountability …

Around 85% of gov revenues come from oil. Most of the $1.5b+ external debt is secured against or repaid in oil. Accountability for all public funds is important, but oil still rules in SouthSudan. But to turn this oil into cash, the gov needs international companies and markets

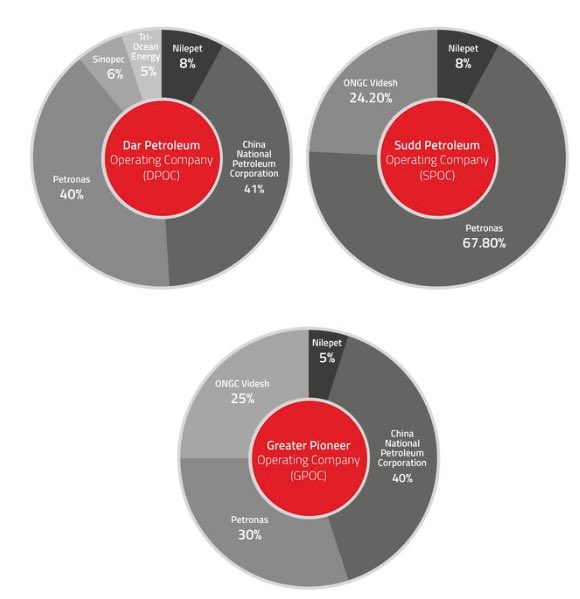

All the oil is produced by 3 joint ventures dominated by large international oil companies, mostly from China & Malaysia. Other international companies supply drilling equipment, expertise, etc.

(Diagram from a @Global_Witness report:

globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/s…)

(Diagram from a @Global_Witness report:

globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/s…)

These companies and the government split the oil roughly 60/40 before it is pumped through #Sudan for export. SouthSudan has little domestic refining or storage capacity. Sudan keeps around 28,000 barrels per day as payment for various fees and debts.

It ends up here, on the Red Sea, near Port Sudan, where tankers ship it off to refineries around the world.

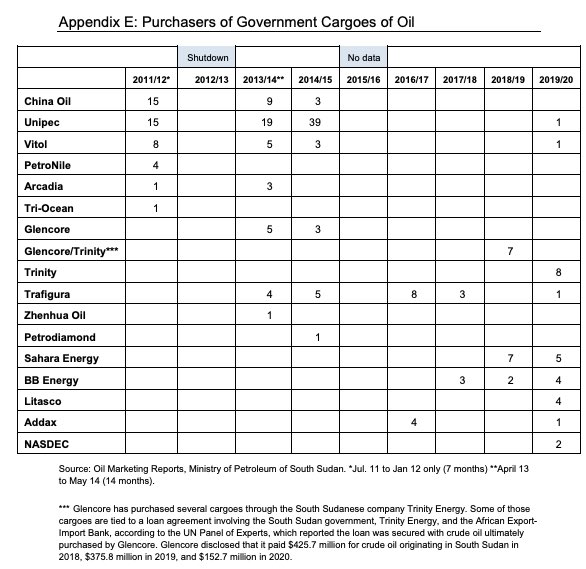

Who buys South Sudan’s oil?

Who buys South Sudan’s oil?

Remarkably, since independence, just 17 companies have bought ALL the government’s oil, with an average of just 5 buyers in any given year. Recently, these are mostly international traders based in Europe and the Gulf.

(according to gov reporting, data from one year missing)

(according to gov reporting, data from one year missing)

This means that in any given year, just a handful of companies make payments that add up to the vast majority of the government’s revenues. And could, in principle, help make these transparent and accountable.

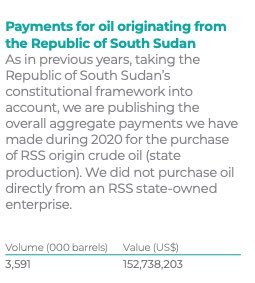

Over the last 3 years, for example, UK-listed @Glencore has disclosed more than $950m in payments for South Sudanese oil, but few other companies have published their payments, making it harder still to check sporadic government figures.

The gov has also been able to borrow against future oil production, often from the same traders, who provide access to international credit markets the gov would not otherwise have. This grows the size of the prize contested in Juba, while creating debt.

occrp.org/en/37-ccblog/c…

occrp.org/en/37-ccblog/c…

Last year, Guyana’s Finance Minister described being “bombarded” with offers of billions in credit from international traders and banks on the sidelines of an IMF meeting, before the country had even started producing oil.

reuters.com/article/guyana…

reuters.com/article/guyana…

This all matters because international companies also shape and profit from South Sudan’s oil industry, and so have an important role to play in ensuring its people do too.

Yet these commercial actors are often overlooked by policy makers and the focus on government officials

Yet these commercial actors are often overlooked by policy makers and the focus on government officials

The full @CrisisGroup report is available from:

crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-af…

@Alanboswell ’s excellent summary of its main points is here:

crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-af…

@Alanboswell ’s excellent summary of its main points is here:

https://twitter.com/alanboswell/status/1445693013309620236?s=21

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh