We had our department's doctoral students' meeting today. High time to share more about the topic I'm working on for my dissertation!

All please welcome #evolution of #altruism!

All please welcome #evolution of #altruism!

Put simply, altruism means unconditionally helping another. You might think it's a human trait, but it's actually present in lots of animal species! Let's have a look at some.

In the previous tweet, you could see an example of guarding against predators. Is that altruism?

In the previous tweet, you could see an example of guarding against predators. Is that altruism?

Keeping guard - called sentinel behavior - makes you more exposed and vulnerable to predators, while it protects others in your group.

Is there a benefit for the sentry?

We'll get to that!

Is there a benefit for the sentry?

We'll get to that!

Other examples include sharing food, aiding the injured, helping at others' nest, nursing others' offspring... For instance, this behavior, called allofeeding, was observed in zebras. Why does it happen?

Satiated vampire bats routinely share blood with those who have gone hungry that night. Bats have fast metabolism and can't survive hungry for too long, so this food sharing is a great aid. What's responsible for the origin of this behavior?

Some of you replying to the thread already guessed a part of the answer, but it's only a part of it, not the full picture. Let's look at the benefits of altruism.

Yes, benefits: in the evolutionary scope, there need to be some for the behavior to persist

Yes, benefits: in the evolutionary scope, there need to be some for the behavior to persist

https://twitter.com/julestw9/status/1446563402013233153

To avoid confusion: psychology and evolutionary biology view altruism through different lenses. Psychology sees an individual trying to sincerely help. Biology looks for the benefits. Yet both are complementary.

How so? Let's ask Niko Tinbergen!

How so? Let's ask Niko Tinbergen!

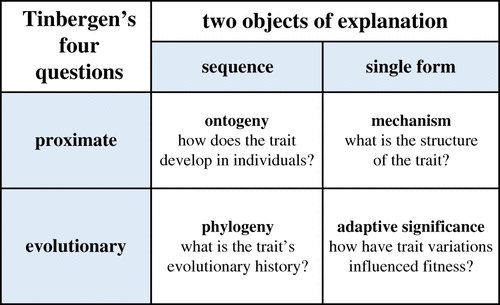

This brilliant ethologist highlighted four levels of explanation for a trait - basically combinations of looking at the big or small picture, short- or long-term.

Psychology asks about the individual development of altruism. Neuropsychology would focus on the neural mechanisms.

Psychology asks about the individual development of altruism. Neuropsychology would focus on the neural mechanisms.

Evolutionary biology, not surprisingly, asks the long-term, big-picture question: How is this behavior adaptive? How could it be selected for?

One answer is kin selection. Basically, it means that if you help your kin, you help pass alleles you also share to the next generation.

One answer is kin selection. Basically, it means that if you help your kin, you help pass alleles you also share to the next generation.

Kin selection appears to be responsible for a lot of acts of altruism, but by far not all! So what else happens there?

Let's look closer at the vampire bats, because experiments showed that kin selection is NOT meaningfully responsible there.

Let's look closer at the vampire bats, because experiments showed that kin selection is NOT meaningfully responsible there.

In a famous study, Gerald Wilkinson looked at the associations of bats - who helped whom, whether they helped back, etc. - and their degree of relatedness, kinship. Helping was predicted far more by previous experience than relatedness.

nature.com/articles/30818…

nature.com/articles/30818…

Apart from observing, the author also experimented, starving a bat each night and seeing if others would help. They would... and later on, those who'd been helped were more likely to help those who'd aided them.

In short, we've got reciprocity.

In short, we've got reciprocity.

Put very simply, reciprocity could be boiled down to "I help you, you help me later". It sounds easy, and it may be for us humans... but it's actually pretty cognitively demanding!

You need to remember many other individuals, your previous interactions, and 'imagine' the future.

You need to remember many other individuals, your previous interactions, and 'imagine' the future.

After William Hamilton proposed kin selection as a frequent explanation for altruism in 1964, Robert Trivers stepped in with reciprocity in 1971. Is that it, rest of mystery solved?

journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.108…

journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.108…

Nah! Like I said, reciprocity is cognitively demanding. Sometimes we can find other explanations. Like harrassment, which probably happens in some cases of allosuckling (nursing another's offspring). For the zebra, giraffe or other mare, it may be easier to give in to the foal.

Even the seemingly clear-cut case of vampire bats may have other influences contributing to the origin of food sharing among them, like pseudoreciprocity (helping others not because of later aid, but bc their presence is benefitting you some other way).

tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.416…

tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.416…

Where there's reciprocity, it need not be direct ("I help you, you help me later"). It can also be indirect ("I help someone, others see it and may be more inclined to help later").

We get reputation.

That's where the sentinels come in...

We get reputation.

That's where the sentinels come in...

We've got a reply saying that meerkat sentinel behavior is not altruism - but that's not entirely certain. In fact, there's still no consensus over meerkats. Some studies supported the altruism option, some didn't. As to guarding and rank...

https://twitter.com/wizabeth/status/1446559058903896102

Sentinel's experience rather than rank seems to predict others' trust in the sentinel's vigilance: nature.com/articles/s4159…

Also, some tend to guard far more than others (observed in the wild as well as captivity), not entirely hierarchy-related: onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.10…

Also, some tend to guard far more than others (observed in the wild as well as captivity), not entirely hierarchy-related: onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.10…

But neither of those studies answers the question of altruism. An older study found that meerkats tend to 'volunteer for guard duty' once their bellies are full and choose safe sites as lookouts. Still, is it more adaptive for them than laying low?

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10356387/

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10356387/

In general, altruistic acts giving you a good reputation may not only lead to a greater chance of aid when you need it, but also show you as someone with resources and capability, a desirable partner. Which gets us to another evolutionary influence of altruism: costly signaling.

Mind you, that might not be the meerkat case, since there are other factors in play - but altruism may be one of the many cases of costly displays of one's worth as a partner, akin to a peacock's tail.

jstor.org/stable/3677205

royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/abs/10.109…

jstor.org/stable/3677205

royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/abs/10.109…

Altruism includes a complex set of behaviors - it appears to have arisen many times independently, and can't be boiled down to a single explanation. In some cases, it may be driven by kin selection; elsewhere reciprocity, costly signaling or other factors and their combinations.

So what can we do to trace its origins? We can observe animals (including people) and run experiments! It's getting late here, but hopefully we'll still have time to get to the game theory of birds and lever-pulling rats and chimps tomorrow. For now - good night, fellow humans.

We're briefly back! So how do we study what mechanisms contribute to altruism in laboratory conditions?

Often, resource division dilemmas and experimental games originally developed for studying people are used, such as the Prisoner's Dilemma, Dictator and Ultimatum Game.

Often, resource division dilemmas and experimental games originally developed for studying people are used, such as the Prisoner's Dilemma, Dictator and Ultimatum Game.

In the Prisoner's Dilemma, imagine two criminals caught by the police. They can each be tried for a minor crime and get a short sentence, but if one talks about a greater one, he walks free and his accomplice gets a very high sentence. If both talk, they get a medium sentence.

No matter what your accomplice does, you're better off talking: if he doesn't, you walk free. If he does, you get a medium instead of long sentence. Even though you'd collectively be better off silent, the game converges to both players talking: the so-called Nash equilibrium.

But people don't work like Nash equilibria machines and often cooperate with each other.

It also gets more interesting if you repeat the games: cooperative strategies conditional on your partner also cooperating, "tit for tat", then win in the long term.

It also gets more interesting if you repeat the games: cooperative strategies conditional on your partner also cooperating, "tit for tat", then win in the long term.

Do animals do something similar? We can modify the game to work with pellets of food and levers or buttons, train the animals to operate the mechanism and then see what happens.

What do you think: Do blue jays cooperate in the Prisoner's Dilemma?

What do you think: Do blue jays cooperate in the Prisoner's Dilemma?

In a 1995 study, blue jays didn't cooperate much in the Prisoner's Dilemma. When the game was switched to yield highest rewards for both cooperating (called mutualism), they did cooperate much more.

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

But it might not be so simple. Food, unlike some IOU like money, is an immediate reinforcer - one tends to prefer immediate payoffs to future ones even more.

If we delay the food-based payoff, cooperation rises higher!

science.org/doi/abs/10.112…

If we delay the food-based payoff, cooperation rises higher!

science.org/doi/abs/10.112…

In order to cooperate reciprocally, not just with simultaneous benefits, one needs to lower temporal discounting: the preference of immediate rewards to future, even if future ones would be higher. In many contexts, it makes sense not to wait. Waiting is also harder cognitively.

That may be the key reason why strict reciprocity seems to be rare in nature, unlike kin selection of reputation-based cooperation and altruism (where especially the latter also needs quite advanced cognition, mind you!).

But it's not the end of the story...

But it's not the end of the story...

If we look at other birds such as zebra finches, we see results similar to the blue jays. But what about mammals? Rats, or even apes? Do you think we get more reciprocity there?

Rats exhibit generalized reciprocity: prior experience of being helped leads to greater willingness to help others.

journals.plos.org/plosbiology/ar…

journals.plos.org/plosbiology/ar…

Later study revealed that rats are also capable of direct reciprocity (helping the one who'd helped them), which is stronger than generalized. Yay for rats! (They're very smart and social animals.)

link.springer.com/article/10.100…

link.springer.com/article/10.100…

Finally, chimps; as close to humans as it can get. A 2007 study showed them helping others to food basically regardless of whether the food allocation was fair or not - whatever their own reward.

science.org/doi/abs/10.112…

science.org/doi/abs/10.112…

However, in this experimental design, using immediate access to food upon completing the task may have influenced the result. When tokens (that the chimps were trained to exchange for food) were used, they weren't exactly enthusiastic about getting less than their colleague...

That subsequent study is here: pnas.org/content/110/6/…

However, that one had its own potential problems with the experimental design: pnas.org/content/110/33…

However, that one had its own potential problems with the experimental design: pnas.org/content/110/33…

In nature, we can see chimps being cruel and selfish as well as helpful and selfless - depends toward whom, much like with us humans!

And with that, I'd like to wrap up the thread. Animals display a remarkable range of complex behaviors, including altruism. We're just beginning to understand its full scope and origins: and while at it, we can see even better with how wonderful creatures we share the world with!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh