After Basil’s first campaign in Syria, he appointed Damian Dalassenos as the new Doux of Antioch. Basil returned to Europe and prepared for war with Bulgaria.

Dalassenos pursued an aggressive policy against the Fatimids. Manjutakin once again besieged Aleppo, but fled when Dalassenos brought his army to relieve the city. In 997, Dalassenos raided around Tripoli and captured the fortress of Al-Laqbah.

In 998, a fire broke out in Apamea, destroying much of the city’s supplies. The Aleppines sent an army to capture the city but retreated at Dalassenos’ approach. The doux wanted to capture the city for the Empire and the Aleppines, disgruntled, left their provisions for the city.

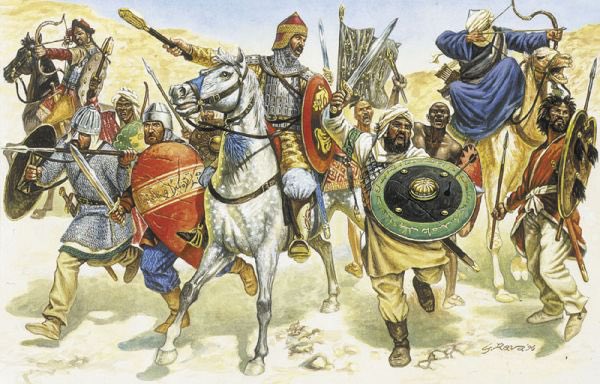

Al-Mala’iti, the governor of Apamea, begged the Fatimids for aid. The governor of Damascus, Jaysh ibn Samsama, set out with 10,000 soldiers and 1,000 Bedouin tribesmen to relieve the city in early July.

The situation in Apamea had become desperate and the residents of the city ate corpses and dogs to survive.

On July 19th, the armies met on a wide plain near the Lake of Apamea. Dalassenos and Samsama’s forces were both roughly 10,000 strong. Dalassenos charged the Fatimid lines and routed them. Soon 2,000 Fatimid soldiers lay dead and the Byzantines captured their baggage train.

Believing the battle won, Dalassenos took off his armor and watched the fighting from a nearby hill with two of his sons and a few retainers.

At this time, a Kurdish cavalryman approached Dalassenos. Dalassenos thought the rider wished to surrender. When the man charged Dalassenos it was too late. The Kurd threw his spear at Dalassenos, killing him.

Word of Dalassenos’ death spread across the battlefield. The Fatimids began shouting “the enemy of God is dead!” The Byzantines lost heart and fled. The Fatimids regrouped fell on the Byzantines, even the starving garrison of Apamea sallied forth to join in the slaughter.

What seemed only hours before to be a decisive Byzantine victory, turned into a disaster. Most of the Byzantine army was killed and many of the survivors were captured, including many senior officers and Dalassenos’ sons.

Samsama then pillaged Antioch’s suburbs and laid siege to the city for a week before returning to Damascus. He didn’t make a serious attempt on the city, but sent a message to Basil: I’ll be back to take it soon.

Messengers rushed across the Empire to deliver Basil the news. Basil made his way to Syria slowly (was he out of mules?) and arrived in the Autumn of 999.

Basil first stopped at Apamea and buried his fallen soldiers. Then the army repeated its moves from the previous campaign, sacking towns and emplacing garrisons in Fatimid territory. The Fatimids did not offer battle.

Basil raided as far as Baalbek in Lebanon and captured the city of Emesa. The Varangians lived up to their terrifying reputation as warriors and raiders.

Sources recount that some citizens of Emesa fled to the fortified monastery of St. Constantine, but the Varangians set it alight, forcing the defenders to surrender.

The Varangians plundered the monastery completely, even stripping the lead and copper ornaments from the roof of the church!

Basil once again besieged Tripoli, this time bringing the navy to blockade the port. This forced the garrison to action and they sallied forth from the city walls, inflicting painful casualties on Basil’s forces. Basil, unable to break into the city, wintered in Cilicia.

Basil, intending to return to Syria in the spring, received ambassadors from the Fatimids. Both sides were tired of the senseless fighting and unable to gain an advantage, brokered a truce.

Basil was more than happy to oblige, he and many of his leading generals saw further attempts to expand east as pointless. This truce also freed him to focus on his real goal: Bulgaria.

By now the people of Syria were familiar with the fearsome Varangians, the sight of their battle axes signaling the presence of Basil himself on the battlefield.

The Varangian Guard had now completed two full campaigns in the service of the Empire and had become integral to Basil’s military strategy as his premier shock troops. Soon they would see action in the long Bulgarian War and cement their legendary status.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh