Okay, time for some thoughts on "unpopularism," which is the closest I have to a synthesis in this conversation.

In short, the missing piece of popularism is what I’d call agenda control. Agenda control requires controversy. You can’t achieve it if you’re afraid to offend.

In short, the missing piece of popularism is what I’d call agenda control. Agenda control requires controversy. You can’t achieve it if you’re afraid to offend.

The media is attracted to controversy. Controversy requires large or powerful groups to be both opposed ands interested.

Most of the time, that requires some degree of unpopularity in your ideas.

Most of the time, that requires some degree of unpopularity in your ideas.

I’m skeptical that polling is that useful a guide to issue popularity, particularly on new issues.

I think it’s more reliable as a guide to which party is favored on broad issue areas, like health care or immigration.

I think it’s more reliable as a guide to which party is favored on broad issue areas, like health care or immigration.

This is a point @DavidShor makes, too. It’s behind his consistent admiration for Bernie Sanders.

Sanders adopts all kinds of unpopular policy ideas and labels, but it’s in service of keeping controversy focused on his broad issues of strength.

Sanders adopts all kinds of unpopular policy ideas and labels, but it’s in service of keeping controversy focused on his broad issues of strength.

https://twitter.com/ezraklein/status/1446522074554507270

Think back to the Medicare for All plan that dominated virtually every Democratic primary debate:

The way it did that was by having unpopular provisions — abolishing private insurance, raising broad-based taxes — that kept it a focal point of controversy.

The way it did that was by having unpopular provisions — abolishing private insurance, raising broad-based taxes — that kept it a focal point of controversy.

If Sanders had created a narrowly popularist Medicare plan — like, say, the Buttigieg plan — it wouldn't have given him the agenda control it did.

(Whether that would've been better or worse for him is an open question.)

(Whether that would've been better or worse for him is an open question.)

This is also relevant to Trump: He said lots of very unpopular things on immigration, but the benefit of that, to him, is it kept the media focused on immigration, which was a better cut for him than economics.

Which is to say: One version of popularism holds that the important thing in politics is deciding which popular things you say.

I think a more compelling version asks which unpopular/controversial things you say in order to define the debate and control the controversy.

I think a more compelling version asks which unpopular/controversial things you say in order to define the debate and control the controversy.

I don’t think Democrats have thought about this question that clearly for the past few years because Trump himself was the controversial subject that drove their mobilization and dominated the issue agenda.

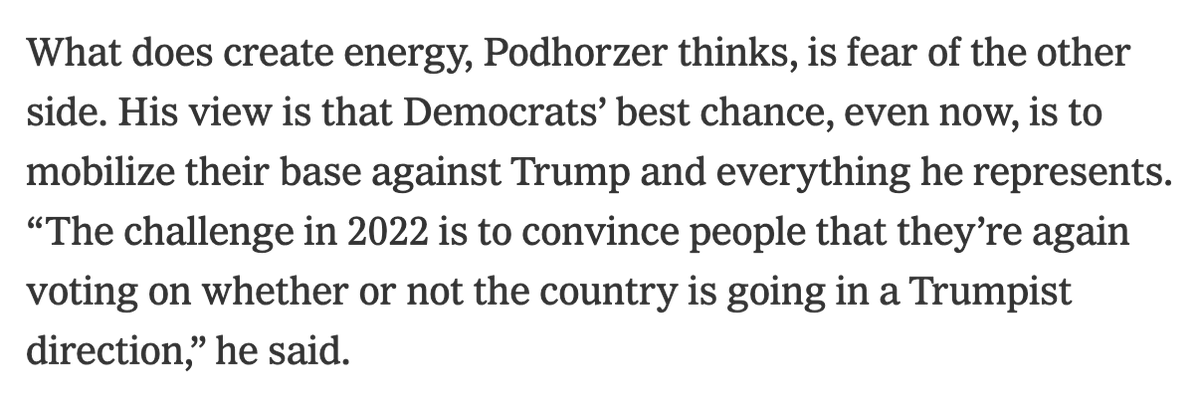

Viralists see that as a strategy Dems need to try and repeat. It's definitely right that negative partisanship unleash huge energy in modern politics. We just saw its power in the CA recall.

But can Dems do it in the midterm, without Trump on the ballot? I'm skeptical.

But can Dems do it in the midterm, without Trump on the ballot? I'm skeptical.

And this isn’t just about elections. You see it in legislative fights too.

The stimulus checks defined the fight over the American Rescue Plan in part because they were controversial. They even had Democratic critics, like Larry Summers, which kept them in the news.

The stimulus checks defined the fight over the American Rescue Plan in part because they were controversial. They even had Democratic critics, like Larry Summers, which kept them in the news.

The reconciliation bill has suffered for not having a flagship, viral policy like that.

Instead the point of disagreement is the $3.5 trillion price tag, which is just terrible ground for Democrats to be fighting on.

Instead the point of disagreement is the $3.5 trillion price tag, which is just terrible ground for Democrats to be fighting on.

Agenda control is central. You need to choose, in a campaign or a leg fight, what your controversial policy will be, and which kinds of unpopular debates you’re willing to risk to keep the broader debate on more popular terrain.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh