I've been thinking alot about this fascinating reporting by @dakekang on Xinjiang. It's really important to understand that absence of visible repression doesn't mean a loosening of state control. Visible violence often means state doesn't have other options. 1/n

https://twitter.com/AP/status/1447147267669037057

@dakekang First, it's a measurement issue: mass public violence is easy to measure. A knock on the door or a disappearance at night is harder for outsiders to see and observe, esp when info is censored. This came up a LOT in my book. 2/

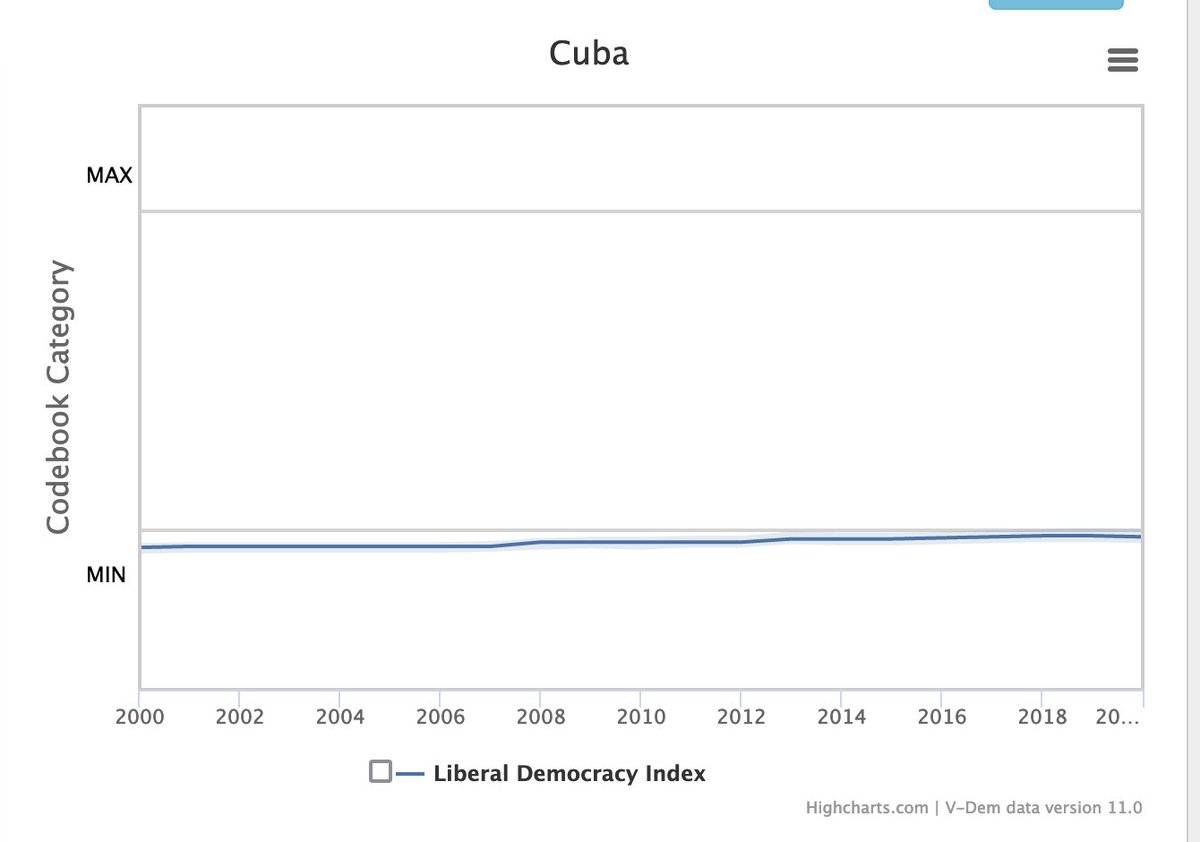

Second, the absence of overt physical violence is sometimes due to the *success* of state/regime repression, not it's absence. Judt called this, in E. European communist regimes, "the peace of the prison yard." 3/n

That's what came across to me in @dakekang's reporting: the internalization of a repressive environment. For China, this may be a short-term win at long-term cost, if preference falsification hides deep anger or resentment. 4/n

PRC discourse measures success by "no major attacks in X years." That's a tactical measure on a short-term time horizon; it doesn't factor in either external costs (which CCP seems to weight not much) *or* long-term domestic security risks to stability. 5/n

The thing that I found most surprising about @dakekang's report was the sentence saying surveillance cameras had been removed. Often surveillance substitutes for other forms of violence because it allows for more preventive demobilization, which has been Xi's stated goal. 6/n

I have lots of questions about that: is it because there are now other ways to track movement that aren't as cumbersome as facial recognition + back-end platforms? Because people now scan in/out of their homes, etc? Maybe. Unclear, & potentially impt. 7/n

But let's also remember that many residents of XJ have cycled thru (or are still in) re-education facilities. If you take the targeted populations (which is the translation I prefer of 重点人口) off the streets, you don't need street cameras as much. 8/n

It may be that the right % of "individuals infected by extremism" have already been re-educated, or are now confined for re-education, & while that happened, the state has built the infrastructure for less visible methods of social control. 9/n

Remember, ~a decade ago Xinjiang had less public security spending per capita than most other provinces/regions, while it was perceived by CCP as having far greater security risks. Chen Quanguo's job, with regime support, was to leapfrog - that's what we've watched. 10/n

Let me give a (much smaller-scale) example: in Taiwan, arrests & executions both dropped sharply after mid-1950s. Why? Because around that time, the KMT got a new internal security apparatus in place: one that deeply penetrated Taiwan society with surveillance/informants. 11/n

We sometimes call both executions & surveillance "repression." Both forms of repression violate rights, but they can have different causes & effects, so it's best to be precise. Lots of great, difficult polisci work on this. 12/n

With two co-authors, I spent months trying to understand why the CCP escalated detention (one form of repression) in Xinjiang in spring 2017. It will take a while to try to find the information to understand what this shift actually *is*, & why it might've occurred. 13/n

Since the Holocaust, scholars have struggled with the ethics of this task: how does one understand abuse, without justifying it? It is morally fraught & taxing to try to understand the thinking of repressive actors. But I would argue it's essential for guiding moral action. 14/n

This thread feels unfinished bc the work of understanding what @dakekang saw is far from over. And it is essential that his work continues, that those affected continue to testify, & that scholars & policymakers grapple w/how to understand what the reports & testimony mean. 15/n

Anyway: point of this is that reduced *visibility* of repression doesn't necessarily mean a) shift in CCP policy, or b) a less repressive environment for human beings in Xinjiang. It's important we as readers & observers understand that.

FIN (unless I think of sth else to add)

FIN (unless I think of sth else to add)

Adding this to thread:

https://twitter.com/sheenagreitens/status/1448322449460895751

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh