In a new study led by @AllieGreaney, we show that infection with a #SARSCoV2 variant elicits an antibody response with somewhat shifted specificity relative to early Wuhan-Hu-1-like viruses that were circulating early in the pandemic: biorxiv.org/content/10.110… (1/n)

It's now known that #SARSCoV2 variants have mutations that reduce neutralization by antibodies elicited by early viruses, which are source of spike in current vaccines. This figure from @VirusesImmunity shows neutralization drops for common variants:

https://twitter.com/VirusesImmunity/status/1447709980514295810(2/n)

But do the antibodies elicited by infection with these variants have different specificities, such that humoral immunity from infection with variants will be differentially affected by specific mutations? (3/n)

To investigate this, we worked w @sigallab @Sandile_Cele22 @farinakarim @khadijakhan24 at @AHRI_News to look at antibodies elicited by B.1.351 variant (ie, Beta). This variant has mutations that reduce neutralization by antibodies elicited by early viruses & vaccines. (4/n)

Importantly, prior work by @sigallab @Tuliodna & Penny Moore already suggests B.1.351 elicits somewhat different specificities, as antibodies from B1.351 neutralize early #SARSCoV2 better than vice versa: nejm.org/doi/full/10.10… & nature.com/articles/s4158… (5/n)

To investigate specificities at higher resolution, we first examined what part of virus targeted by neutralizing antibodies elicited by early 2020 #SARSCoV2 & B.1.351. Both elicited neut activity dominated by anti-RBD antibodies, especially B.1.351. (6/n)

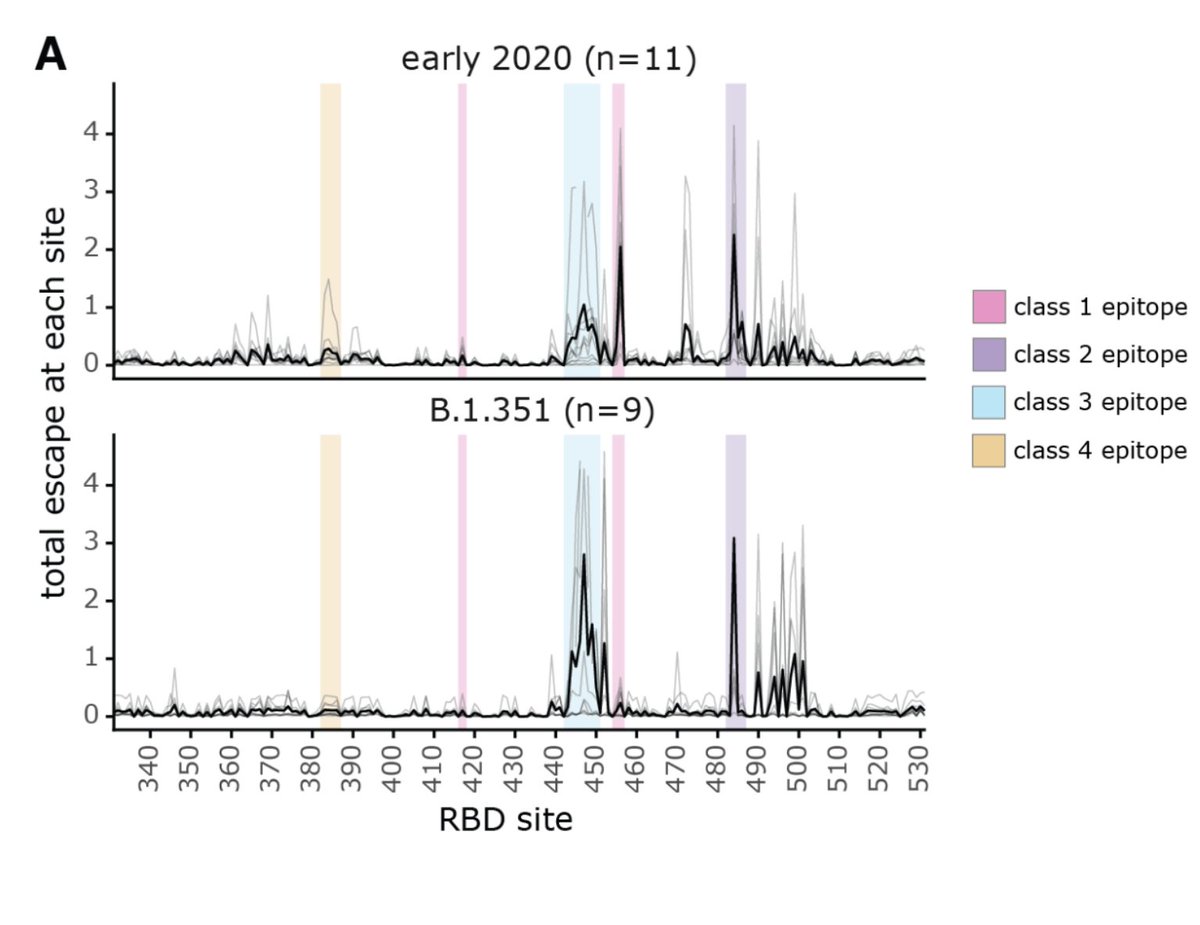

@AllieGreaney then used deep mutational scanning developed w @tylernstarr to see where in RBD antibodies elicited by variants bind.

We can divide RBD in 4 major epitopes using scheme of @cobarnes27 @bjorkmanlab: B.1.351 has antigenic mutations in class 1 & 2 epitopes (7/n)

We can divide RBD in 4 major epitopes using scheme of @cobarnes27 @bjorkmanlab: B.1.351 has antigenic mutations in class 1 & 2 epitopes (7/n)

Our results show that antibodies elicited by B.1.351 are notably more skewed to class 3 epitope, although they still target class 2 epitope quite a bit. (8/n)

These differences also hold up in neutralization assays. For instance, mutations at class 2 epitope sites like 484 can dramatically decrease RBD-directed neutralizing activity of serum antibodies from early #SARSCoV2, but cause much milder drops for B.1.351 elicited sera. (9/n)

So what does all this mean? At a very specific level, perhaps not much: as @trvrb has noted (

But we think the *principle* will hold more broadly. (10/n)

https://twitter.com/trvrb/status/1447566587700006926), other variants including B.1.351 have largely been outcompeted by Delta.

But we think the *principle* will hold more broadly. (10/n)

RBD mutations in B.1.351 are also showing up in some Delta variants, and more generally the virus will continue to evolve. As it does so, keep in mind that this evolution will shift which sites are immunodominant, and so which mutations have the largest antigenic effects. (11/n)

Therefore, it will be important to keep in mind that our understanding of the "antigenic structure" of the #SARSCoV2 spike might need to continually be assessed as immunodominance hierarchies start to shift. (12/n)

Thanks to our collaborators; in addition to ones already mentioned: @HelenChuMD @veeslerlab @DavideCorti6 @eguia_rachel A Loes, @johnbowenbio, J Logue.

Finally, all our antibody & sera deep mutational scanning available for viewing & download at jbloomlab.github.io/SARS2_RBD_Ab_e… (13/n)

Finally, all our antibody & sera deep mutational scanning available for viewing & download at jbloomlab.github.io/SARS2_RBD_Ab_e… (13/n)

See also this nice summary by @AllieGreaney:

https://twitter.com/AllieGreaney/status/1448637440927830017

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh