Honestly not a big fan of the case trends in the last couple of days. Here’s the overview: with the kids still driving the growth, but other groups also starting to pick up. (and I wouldn’t take too much cope from the flattening on the last day – that will get revised up) 🧵

Looking in more detail at the under-20s, we can see the power coming from the 5-9s, but with 0-4 and 10-14 not far behind, and even 15-19s now back into positive territory (i.e. cases growing)

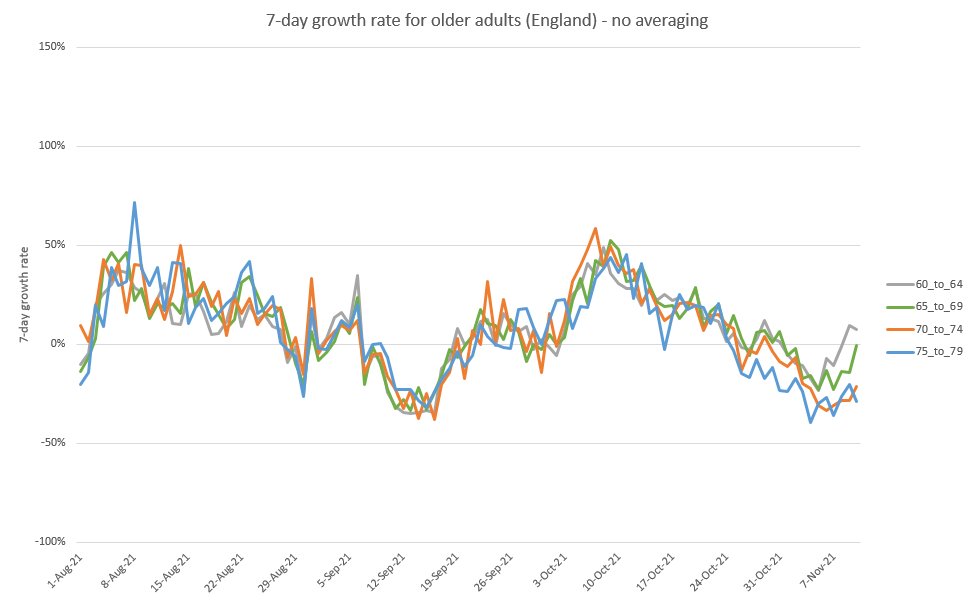

And we now see 60-64 returning to growth, and 65-69 looking like it will get there soon. We really need to get more boosters in those arms, and fast. Fortunately 70-79s (where booster rates are already high) are looking OK, with cases still declining.

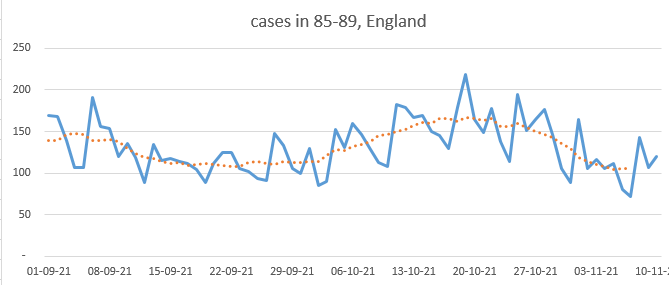

But what’s going on here, with 85-89 and 90+ both back in growth. They've already have good rates of boosters, so is it spreading in the unboosted?

It’s not a big shift (as you can see in the raw case data here for the 85-89), and some of it could just be noise, but it does look like the downward trend has been interrupted. And that’s not great news for hospitalisations next week.

Still, as the bunny says, we should probably wait a few days before jumping to conclusions. I'm going back to watching the rugby now (go England!), but I'll be keeping a close eye on this too over the next few days. /end

https://twitter.com/BristOliver/status/1459189690398085124?s=20

sorry, managed to break the thread here:

https://twitter.com/JamesWard73/status/1459595623087448070?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh