The news from today’s case data continues to be good, but because I can only do undiluted positivity for so long before providing some balance, I’m going to give you the good news quickly, and then give you four reasons to avoid premature celebrations.

First, the good news: case growth in school-age kids continues to decline, and even more quickly in the last day or two. (note: this latest cliff-edge is undoubtedly exaggerated by the impact of people doing fewer LFD tests last weekend, as half term started for most kids)

In particular we can see the 10-14s now clearly over a peak: (best to look at that orange dotted line, which is a 7-day centred average, for an indication of the trend)

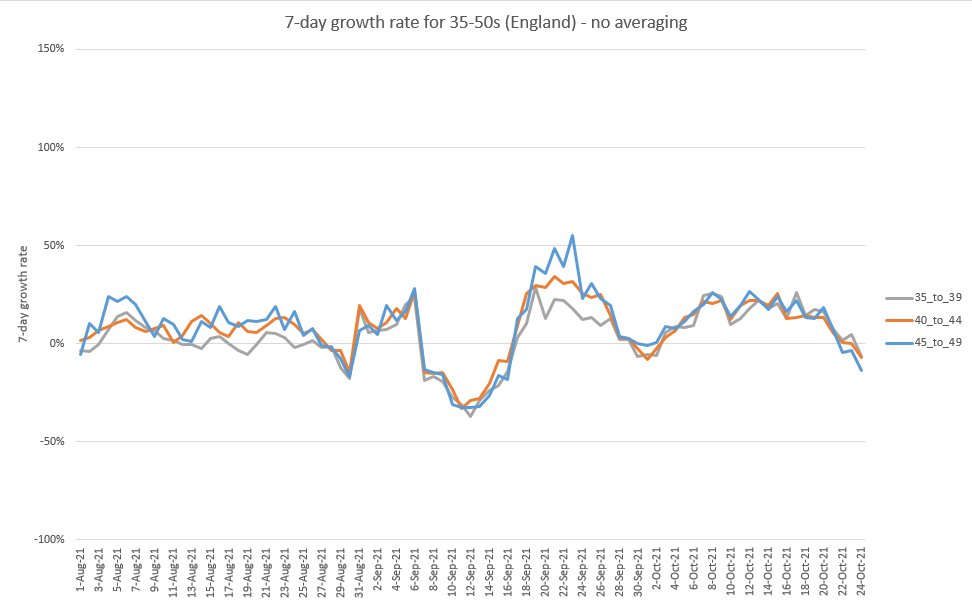

Looking at the age groups together, we can see continuing declines in growth (but not yet falling cases) in the 20-40s and in the 60-80s.

Now reasons for caution:

1) As noted, half term is definitely exaggerating the rate of fall in cases. And while I don’t think that has been a big factor over the last week, it’s possible that early half terms and year group closures have had some effect in pushing cases down.

1) As noted, half term is definitely exaggerating the rate of fall in cases. And while I don’t think that has been a big factor over the last week, it’s possible that early half terms and year group closures have had some effect in pushing cases down.

2) While cases in under-20s are definitely falling, cases in 80+ seem roughly stable, and they’re still growing in 60-80s. We’d expect that to flow through to admissions and deaths – and while England hospitalisations seem to have plateaued, that may just be noise in the data.

Given the current level of pressure in the NHS (ably documented by @ShaunLintern and others), even small additional loads from extra covid admissions are highly unwelcome.

https://twitter.com/ShaunLintern/status/1453387982107512838?s=20

Note that stable cases in the 80+ suggests the combination of boosters + infections is roughly balancing the impact of waning immunity in this group - if we want cases and admissions to fall sharply, which we do, then we need to materially speed up the booster rollout programme.

3) Looking at that age group chart again, we can see examples in the past (e.g. in early September) when growth fell, but just caused a plateau in cases, and then resumed an upwards trend (growing cases).

We don’t want that to happen here – and while I don’t think this is the most likely scenario, I can’t completely rule it out e.g. if after half term we get some colder/wetter weather, and some more relaxed behaviour as overall case rates fall.

4) Even if, as I think is more likely, cases do continue to fall (including in older age groups) for some weeks after half term, we’re not necessarily out of the woods quite yet. In fact, the lower the cases fall in November/December, the more worried I become about Jan & Feb.

This is because, if cases fall below their equilibrium level (whatever that is), we will be building up immunity debt, and there is then a significant risk of a resurgence in early 2022 if boosters don’t come through quickly enough to stop it.

So if cases do crash before Christmas, I’ll be the guy reminding you not to put up banners on aircraft carriers and declare this thing “over”. Sorry to inject a note of caution into a good-news day- I just don’t want us to get carried away by a few green figures on the dashboard.

/end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh