I’ve been thinking a bit about optimism and pessimism, and how that might affect our views on whether additional restrictions (such as the government’s “Plan B”) should be imposed. It’s not quite as simple as it might first appear. Let me explain…. 🧵

The first thing to note is that optimism and pessimism can operate on different timescales. So you might think that things are going to get worse over the next couple of months, but that 2022 will be a more positive experience, due to boosters and improved treatments.

Or you might be relatively optimistic about the next couple of months, but concerned about the potential for a resurgence in early 2022 as we reach the depths of midwinter, and as waning immunity hits the populations in their 40s and 50s who may not have had a booster yet.

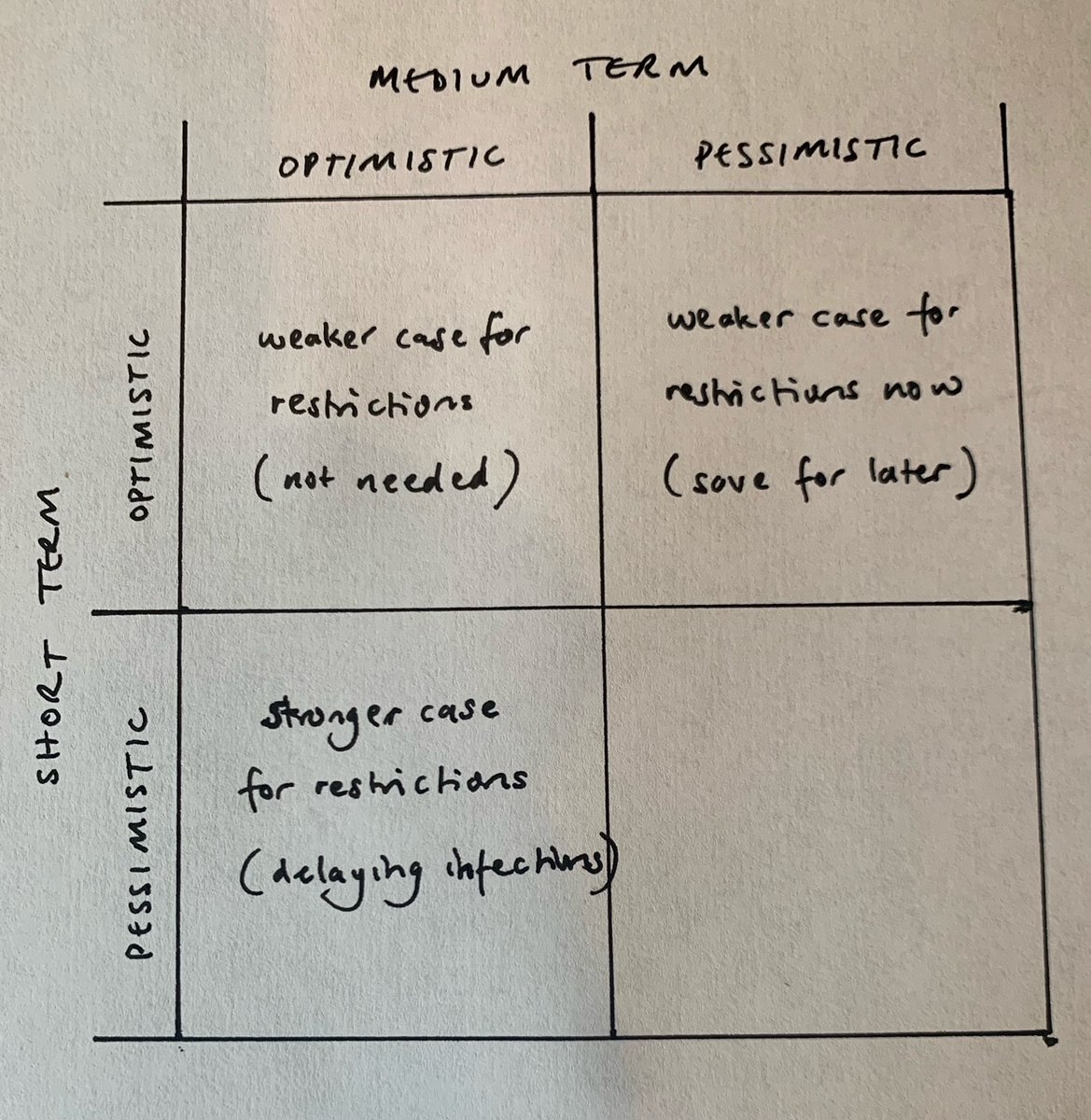

So, digging into my strategy toolkit, let’s form ourselves a 2x2 grid, with an optimistic/pessimistic split on each axis: one for the short term (Nov & Dec 2021) and one for the medium term (first half of 2022).

If we did think that case rates were going to take a short break over half term, and then resume their upwards trend (particularly in older ages) – but that things were going to improve in the New Year, then that could support a case for temporary restrictions, ...

effectively delaying the potential for infections to a point where there is more vaccine-based immunity in the population – and hence reducing the total number of cases, admissions, and deaths. So let’s enter this onto the grid as follows:

Conversely, if we expect a continued decline in cases and admissions over the next month or two, but are worried about a resurgence in 2022, that provides weaker support for introducing restrictions at this point –not least because, as I’ve argued elsewhere, suppression before...

… a peak is likely to make the following peak higher (and later), not lower. In this case we’d do better to keep the restrictions in our back pocket until we’re on the upswing of the next peak, and consider using them then, if at all. So this forms our next entry on the grid:

Now let’s consider the other diagonal. What if we are optimistic about the short term, and about the medium term? Well then things are looking good, and it’s hard to see the case for additional restrictions. So this can also go on our grid:

And finally, if we’re pessimistic about the short term and the medium term, then we’re in for a tough winter, and frankly we’re going to need all the help we can get. So restrictions are more likely to be on the cards for the duration, and we can complete the grid, as follows:

What we see from this grid is that it’s really our view on the short term that guides our thinking on the need for restrictions. Our view on the medium term might influence *why* we think it’s a good or bad idea to add more restrictions, but it’s unlikely to change that view.

Of course, none of this forms a case for or against restrictions, and I haven’t tried to do any cost-benefit analysis on any specific proposals. I’m just interested in how optimism and pessimism, over different time horizons, might influence that thought process. /end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh