As Chinese state media worked to shift the narrative around Peng Shuai, they got help from a familiar resource: a big old bot network. We turned up 97 fake accounts amplifying and claiming to believe the creepy proof-of-life posts from state media: nytimes.com/interactive/20…

Twitter took down the ones @nytimes and @propublica identified and likely 100s more. It says it's investigating. The accounts mostly pretended to believe Peng was safe and free. Some echoed state-media attacks against foreign media and governments that had expressed concern.

They were part of a broader network of 1,700 accounts we found that pushed other propaganda points, linking #StopAsianHate to articles critical of China and hitting out at usual targets like Guo Wengui and Steve Bannon. They posted mostly during China work hours:

As bleak as Peng's accusations and stage-managed appearances have been, it has been fascinating to watch China's propaganda and censorship system run the playbook, and fail. Silence at home, denial abroad, then finally a turn to China vs. the West has mostly made things worse.

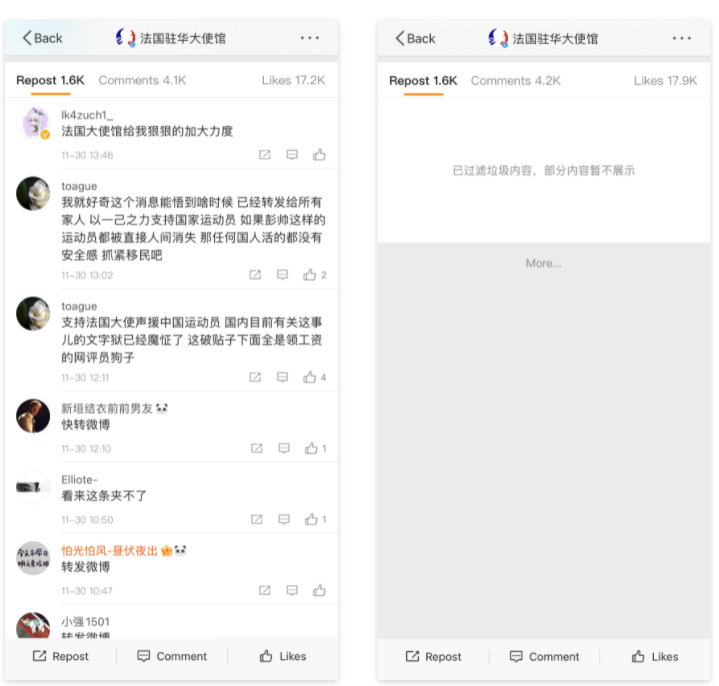

Even on China's censored internet, a turn to nationalism failed. For at least 10 days on Weibo, the only uncensored post on Peng was a French Embassy criticism. In the controlled comments section, posts lashed out against the meddling French. One told them to retreat.

Even so, in the reposts section, commenters gave kudos to the French. Eventually all of the reposts were deleted and the embassy post was removed from search results for Peng Shuai. The domestic turn to nationalism had, at least for now, failed.

One commentator likened the whole thing to a fire truck pouring gasoline on a fire. They "buried their heads in the sand and made these theatrical scenes, one after another," he said. “If someone says they’re free, while they’re in the hands of a kidnapper, that is terrifying.”

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh