Debunking The myth of the

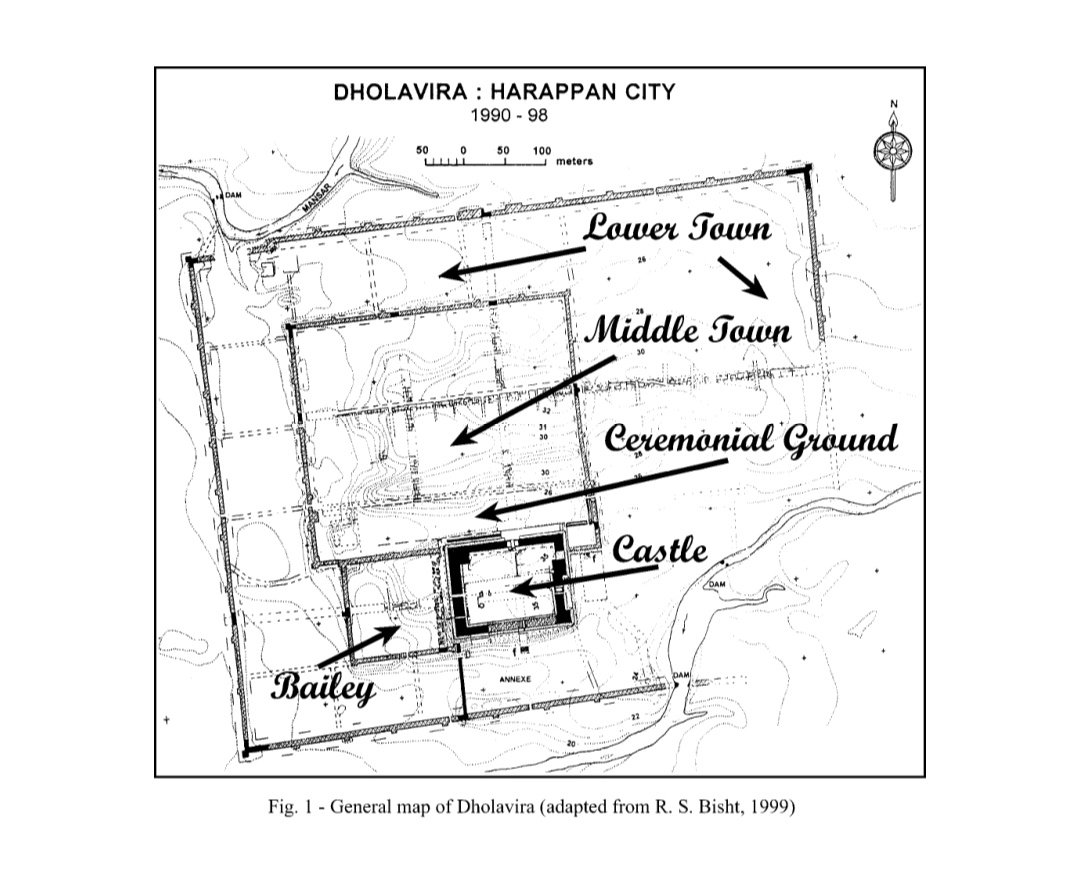

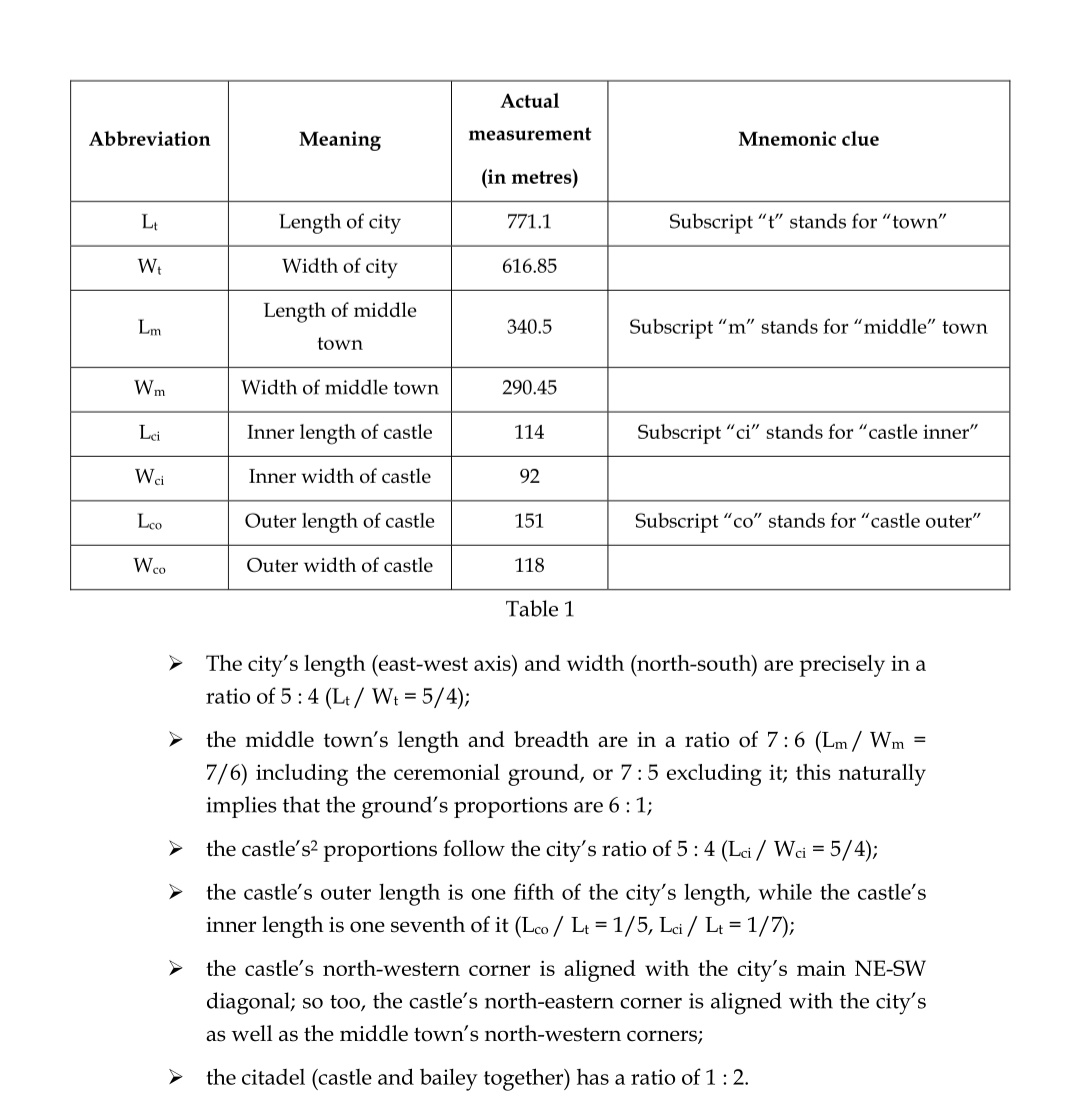

So-called "Puras(forts)" in RigVeda, which According to Parpola was in BMAC where forts in circular shapes were found, the shape described in the early parts of the Rigveda as the enemy forts of Indra.

So-called "Puras(forts)" in RigVeda, which According to Parpola was in BMAC where forts in circular shapes were found, the shape described in the early parts of the Rigveda as the enemy forts of Indra.

Parpola (1988) extracts the Rgvedic verses where Indra, the purandara 'fort-destroyer' is active in the destruction of the ninety-nine or hundred puras 'forts' of his enemies, the Dasas. Based on a verse from the Satapatha Brahmana (6.3.3.24-25),

and drawing on the work of Wilhelm Rau, Parpola proposes that a significant feature of these forts is that they are tripura, or have a threefold structure

Parpola takes this to mean not only that the forts are surrounded by concentric circular walls but also that the forts themselves are circular in construction.

Divodasa's chief enemy, Sambara, possessed a hundred (or ninety-nine) forts and was said to have resided in a mountainous domain. This, according to Parpola, could have been Bactria, northern Afghanistan, there is a site in this area called Dashly-3, dated to about 2000B.C.E.

The site, although surrounded by square walls, consists of various buildings, among which stand three concentric walls. Although these urban structures are a far cry from the temporary mud and wattle purs reconstructed by Rau, these three walls

correspond, for Parpola, to the tripura of the Dasas. He believes he has found the evidence representing the Dasa forts attacked by the Aryans on their way to the subcontinent

K. D. Sethna, who is questioning the very assumption that the Indo-Aryans need be considered intruders at all, has dedicated half of the second edition of his book The Problem of Aryan Origins (1992) to critiquing Parpola's 1988 article

Since all the specific objections against each step of Parpola's reconstruction are quite voluminous and painstakingly argued, one example (central to Parpola's theme) of how Sethna sees the "evidence" being artificially construed to fit a series of assumptions will suffice for

our purposes.

Sethna finds the passage from the Satapatha Brahmana upon which Parpola bases his case of concentric walls actually describing the gods as fearful lest the Raksasas, the fiends, might slay their Agni

Sethna finds the passage from the Satapatha Brahmana upon which Parpola bases his case of concentric walls actually describing the gods as fearful lest the Raksasas, the fiends, might slay their Agni

The passage explains why the priest draws three concentric lines around the fire during a particular ritual. The practice, mentioned in two other places in the Brahmanas, is enacted to ward off demons during the performance of the sacred rites.

Sethna points out that, first of all, the three walls represent fire (agnipurā), not stone and mortar. Parpola has reified a magico-ritualistic ceremony into a real-life fortification.

Second, it is the Aryan sacrificers who are drawing the sacred lines (or building the forts as per Parpola), not the Dasas or Asuras, as Parpola's version requires.

Moreover, neither the word tripura nor any of its associations mentiond earlier occur anywhere in the Rgveda itself

Moreover, neither the word tripura nor any of its associations mentiond earlier occur anywhere in the Rgveda itself

in the Rgveda, We have seen the puras are described variously as wide and broad, made of stone, made of metal, hundred-curved, or with the strange epithet '"autumnal," but there is no mention whatsoever of three concentric walls

Sethna examines a passage from the Aitareya Brahmana, which Parpola also quotes to support his case, and finds a cosmic drama recorded where the gods and the Asuras are competing for the three worlds: The Asuras make the earth into a copper fort, the air into a silver fort, and

the sky into one of gold; the gods counteract these three forts by constructing three different types of sacrificial sheds connected with the Vedic yajna to counteract the respective three forts of the Asuras.

As far as he is concerned "neither the forts of the Asuras nor the 'counter-forts' of the gods in this account can by any stretch of the imagination be visualized as concentric" (Sethna 1992, 298)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh