The opening seminar for the Indonesian G20 presidency was a good opportunity to take stock of #bottlenecks and #inflation risks

A thread follows

bis.org/speeches/sp211…

A thread follows

bis.org/speeches/sp211…

https://twitter.com/BIS_org/status/1468874062227288068

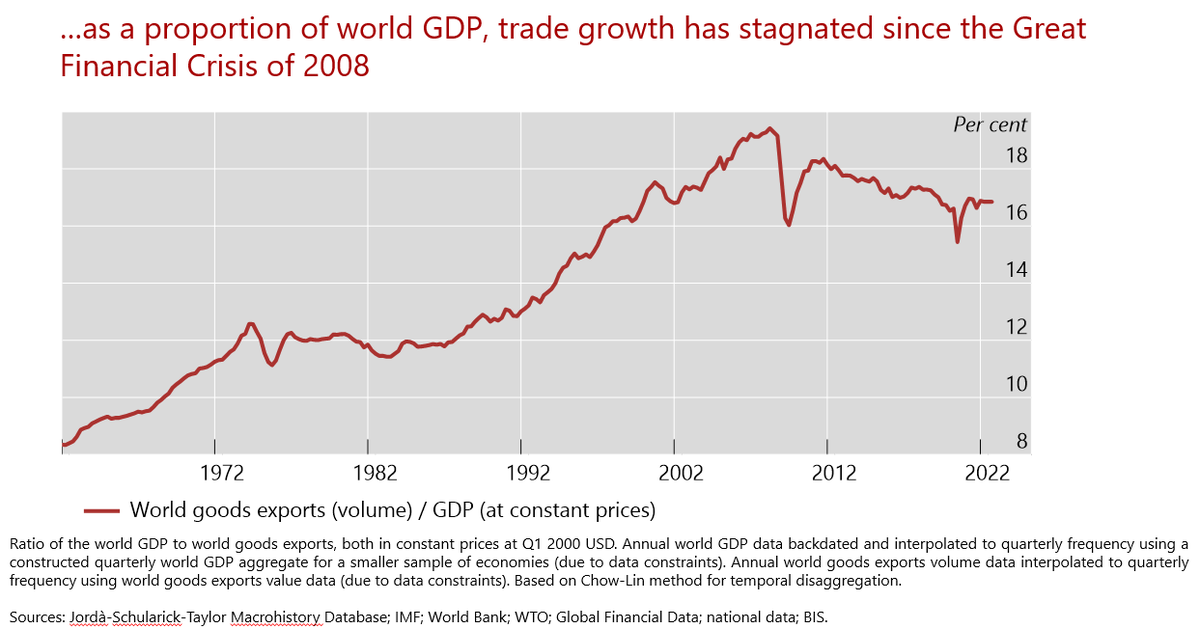

Supply bottlenecks have grabbed all the headlines recently, but longer-term structural changes brought about by the pandemic (labour markets, especially) are important to understand where we are headed

bis.org/publ/bisbull47…

bis.org/publ/bisbull47…

But first, a recap of where we stand on #bottlenecks

The sharp swings in some commodity prices (lumber, iron ore, coal) are suggestive of #bullwhip effects

For their part, shipping costs look to have peaked

The sharp swings in some commodity prices (lumber, iron ore, coal) are suggestive of #bullwhip effects

For their part, shipping costs look to have peaked

Semiconductor billings (left panel) point to demand that has outpaced supply that is growing, but not growing fast enough;

#bullwhip effects show up in rising motor vehicle inventories at the factory, even as retail inventories have fallen

#bullwhip effects show up in rising motor vehicle inventories at the factory, even as retail inventories have fallen

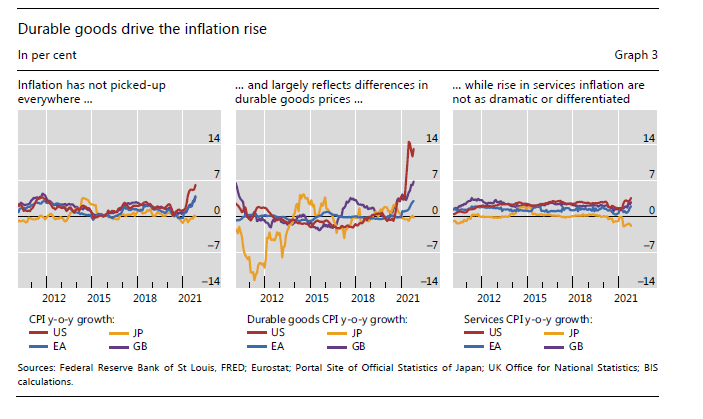

Durable goods have driven the surge in #inflation (middle panel), especially in the United States

But there is a great deal of diversity across regions; Asia has not seen the same surge in inflation

But there is a great deal of diversity across regions; Asia has not seen the same surge in inflation

We should not disregard inconvenient price changes, but it's worth pointing out how unusual the surge in durable goods prices is; it bucks the trend of falling relative price of durables over the last few decades

How quickly will #bullwhip effects go into reverse once backlogs begin to ease? Depending on the answer, we may find that bottlenecks are resolved faster than currently feared, just as they have lasted longer than initially expected

But there is something of a race against time; if the current inflation surge feeds a wage-price spiral and rising inflation expectations, the task will be much harder

Hence my focus on labour markets in today's presentation at the G20

Hence my focus on labour markets in today's presentation at the G20

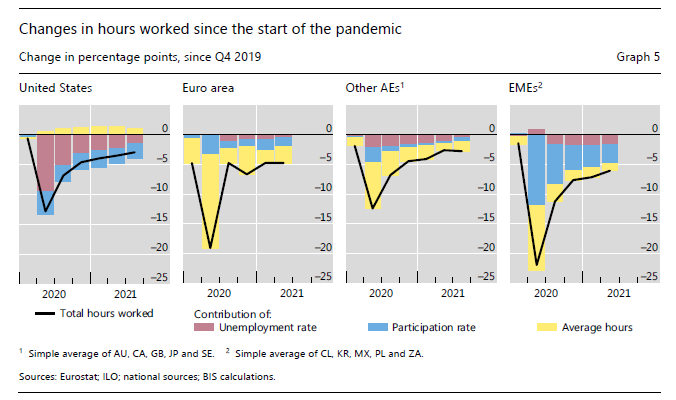

The trajectory of total hours worked is similar across regions; hours fell by 10-20% with the pandemic shock and have bounced back since

But these similar trajectories have come about in strikingly different ways

This chart holds the key to some puzzling developments

But these similar trajectories have come about in strikingly different ways

This chart holds the key to some puzzling developments

There are three ways that hours worked could fall:

(1) increase in unemployment, (2) drop in average hours worked per employee, and (3) a decline in labour force participation

The respective roles of these three factors differ widely across economies

(1) increase in unemployment, (2) drop in average hours worked per employee, and (3) a decline in labour force participation

The respective roles of these three factors differ widely across economies

In the US, unemployment and labour force participation account for the fall in hours worked;

In the euro area and other AEs, furlough schemes kept worker-firm relationships intact (yellow bars);

EMEs were hit hard by the pandemic and labour force participation dropped sharply

In the euro area and other AEs, furlough schemes kept worker-firm relationships intact (yellow bars);

EMEs were hit hard by the pandemic and labour force participation dropped sharply

The differences in the way that hours worked declined have influenced the shape of the recovery;

Evidence is in the Beveridge curves across countries

Evidence is in the Beveridge curves across countries

The Beveridge curve plots the relationship between the unemployment rate and job vacancies

Normally, changes in economic activity would show up as shifts *along* the Beveridge curve with stronger activity showing up as lower unemployment and higher job vacancies

Normally, changes in economic activity would show up as shifts *along* the Beveridge curve with stronger activity showing up as lower unemployment and higher job vacancies

Check out this podcast where @tracyalloway and @TheStalwart speak to Thomas Lubik on how to read the evidence from the US

bloomberg.com/news/articles/…

bloomberg.com/news/articles/…

Rather than moving *along* the Beveridge curve, the US has seen a rightward shift, usually seen as a sign of a skills-jobs mismatch

But there is no such shift in euro area or Japan; and the UK Beveridge curve has started to drift out since the middle of the year

But there is no such shift in euro area or Japan; and the UK Beveridge curve has started to drift out since the middle of the year

Usual interpretation of a rightward shift in the Beveridge curve is as a mismatch between jobs and skills; after the GFC there was a reallocation from the real estate sector

But this doesn't work this time round; vacancies are highest in services that saw the largest job losses

But this doesn't work this time round; vacancies are highest in services that saw the largest job losses

In any case, the contrast *across* countries is very striking; in the euro area and Japan, there is no sign of any deterioration of the jobs-skills match

In this sense, preserving the employment relationships appears to have steered the recovery toward the pre-pandemic state

In this sense, preserving the employment relationships appears to have steered the recovery toward the pre-pandemic state

We need to understand better these differences; firms and workers are part of the intricate web of relationships in the economy with relationship-specific capital that acts as the “glue” for the economy

@B_Eichengreen has written eloquently on the topic

project-syndicate.org/commentary/cov…

@B_Eichengreen has written eloquently on the topic

project-syndicate.org/commentary/cov…

The ties that bind all of us as colleagues, neighbours, workers and employers arguably go beyond the transactional nature of the weekly payslip

On the other hand, the recent upward drift in the UK Beveridge curve from the middle of 2021 suggests that any simplistic explanation will be found wanting, as the UK had also implemented furlough schemes similar to euro area economies

How these differences in labour market functioning translate into wage growth is key for #inflation, but wages are particularly hard to read at the moment due to pandemic related shifts in the composition of employment and the effect of furlough schemes

bis.org/publ/bisbull47…

bis.org/publ/bisbull47…

Wage growth across advanced economies looks to have been in line with its pre-pandemic trends, or a little below; and here, the outcomes of recent wage negotiations are filling in much needed detail...

It is notable that in the United States, where labour market changes are most apparent, wage growth has picked up recently despite labour market conditions that appear weaker than before the pandemic

Let me gather the links in one place for easier reference

Text of my G20 speech

bis.org/speeches/sp211…

Text of my G20 speech

bis.org/speeches/sp211…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh