It's time for a @threadapalooza on Hans Jonas (1903-1993), a brilliant and under-appreciated philosopher, theologian, and scholar of "Gnosticism," who fled Nazi Germany to teach at the New School, and who was a pioneer in the fields of bioethics and environmentalism.

Jonas was a Jewish student of Heidegger's, whose thought, like Arendt's and Levinas's, is at once oppositional to and indebted to Heidegger's. 2

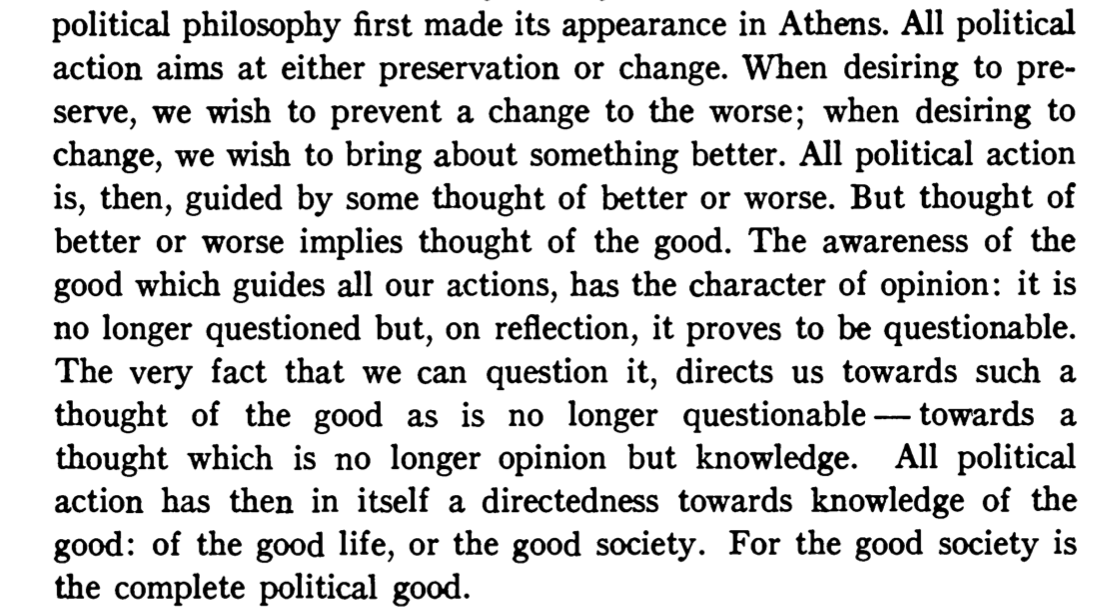

I should add Leo Strauss to the list above. 3

Jonas thinks Heidegger's thought is the apotheosis of all that's wrong with modernity. And yet, the story Jonas tells about modernity, and the methods he uses to tell this story are, lo and behold, deeply Heideggerian! 4

Let's get to it. What's wrong with Heidegger? What's wrong with modernity?

For Jonas, the essence of Heidegger's thought, and of modern thought, generally, is to be found in late antiquity, in the theology known as Gnosticism. 5

For Jonas, the essence of Heidegger's thought, and of modern thought, generally, is to be found in late antiquity, in the theology known as Gnosticism. 5

Gnosticism, which Jonas uses as a catch-all term for any worldview that has this feature, posits the world as the work of a deceiver or a demon, and the true God as standing beyond the world. The technical term for this is "a-cosmism": God/truth is not in the world. 6

A skepticism about the world, a sense of alienation, is core to the Gnostics, be they Jewish, Christian, Zoroastrian, or pagan. The strain runs through all worldviews, and continues to this day...7

There's a conspiratorial element to the Gnostic, who imagines that a demiurge is out to get him, who does not trust the senses and who sees all conventional meaning as a snare. 8

The gnostic believes in transcendence, but believes it's out of reach, or that it's out of reach to reason, to civilization. Kafka is a great example, perhaps, of a gnostic. Scholem might be another. 9

Here's a salient Kafka quote that expresses gnosticism: the law is "valid, but without significance."

Or another: "There's infinite hope, plenty of hope, but not for us." 10

Or another: "There's infinite hope, plenty of hope, but not for us." 10

Jonas's insight is two-fold. First, he understands gnosticism to be a cross-cultural phenomenon. Second, he understands it to be a trans-historical one; it's a structure of thought, a constant "temptation." It belongs to ages that are in crisis. Gnosticism isn't going away. 11

The new move is in seeing gnosticism as a kind of undercurrent of Western thought, rather than an isolated phenomenon.

He does for gnosticism what Gershom Scholem did for Kabbalah. (The two were peers who influenced one another; Jonas found much Kabbalah to be gnostic). 12

He does for gnosticism what Gershom Scholem did for Kabbalah. (The two were peers who influenced one another; Jonas found much Kabbalah to be gnostic). 12

Jonas published his magnum opus on the topic as the Gnostic Religion: The Message of the Alien God & the Beginnings of Christianity, in 1958, but the research was already in the works since the 30s, an ominous time! 13

When you take Jonas's view of Gnosticism seriously, all of a sudden a lot seems Gnostic. Nietzsche and Marx, Freud, all the hermeneutics of suspicion. Lyotard. Butler. Foucault. Althusser. Baudrillard. But also much in pop culture. Blue pills & red pills, the Matrix. Gnostic. 14

Long story for another time, but I once met a self-identified Gnostic and Heideggerian (he embraced the label as a positive). He claimed that gnosticism is about "gnosis": knowing the truth through being initiated into mysteries otherwise off limits to sane reason. 15

There's a massive suspicion to the gnostic, a pessimism about the world and reason that is at the same time, often, a self-aggrandizement. 16

Nobody understands us! How could they. Standpoint epistemology, if you will, is a species of gnosticism. Identity politics is a kind of gnosticism. For gnosticism says that only the knowers know, while everyone else is in the dark. There's no "public reason." 17

We could say gnosticism is politically authoritarian and anarchic all at once.

It's authoritarian b/c it delegates authority only to the prophet who knows we are deceived and how to outsmart the deceiver.

It's anarchic b/c all authority is seen as artifice, in on the con. 18

It's authoritarian b/c it delegates authority only to the prophet who knows we are deceived and how to outsmart the deceiver.

It's anarchic b/c all authority is seen as artifice, in on the con. 18

So how is Heidegger a gnostic, according to Jonas?

1. Heidegger's language of being thrown into the world and fallen evokes a sense of being cut off from the true source.

2. There's no redemption or eternity in Heidegger, just the horizon of time.

3. Death is final.

19

1. Heidegger's language of being thrown into the world and fallen evokes a sense of being cut off from the true source.

2. There's no redemption or eternity in Heidegger, just the horizon of time.

3. Death is final.

19

4. Morality is a project of Dasein, not a true code.

5. Society is depicted in a negative light as a source of "hearsay" (Gerede) and unhealthy socialization (herdlike conformity). "Das Man." Doing as one does. Going along with the big lie!

20

5. Society is depicted in a negative light as a source of "hearsay" (Gerede) and unhealthy socialization (herdlike conformity). "Das Man." Doing as one does. Going along with the big lie!

20

Existentialism (Heidegger denied being an existentialist in his "Letter on Humanism" of 1946), says Jonas, is about the human being unmoored from God and from truth. Life is a project, but there is no path that is right or wrong. We are abandoned on this earth. 21

Heidegger's language does vibe with this description, even if Heidegger himself was likewise unhappy with subjectivism and relativism. For example, Heidegger says we do not know how to dwell. He says we live in a time of Being's oblivion. He says "Only a God can save us." 22

Term clarification. Subjectivism=the idea that I get to decide what truth is. We see this all the time in the pop vernacular of speaking one's truth. Sure we have a unique pov, but if truth is fundamentally just mine, than there's a solipsism to expressing oneself. 23

Confessional culture is a histrionic symptom of a sense of being out of whack. But with what? We are so out of whack we cannot say. The gnostic worldview knows God to be other, but because God is other, we can't say more. We testify in the negative. 24

This is not to say confessional culture is bad per se, but that it's a symptom. Why are we always telling the world our traumas on tiktok? Because of a fundamental loneliness, a loneliness, Jonas might say, having to do with acosmism. 25

Modernity brought technological progress and moral and political emancipation and so called enlightenment, but it didn't make us less alienated. In some ways it intensified our sense of alienation. 26

Sure this is a theme to be found in luddite anti-technologists, but not only them. It's not just a nostalgia for the time before the steam engine. In fact, we have always been prone to gnosticism. 27

For Jonas, modernity begins in antiquity. (We find this theme in Heidegger, too, who sometimes dates modernity to Plato, and in Levinas, who dates it to Parmenides!) The problem isn't the French Revolution, lol. That's just a symptom. 28

In the Deep Places @DouthatNYT entertains the suggestion by @slatestarcodex that our private suffering is even worse and more widespread than the statistics about anxiety, depression, and the opioid epidemic let on. 29

Prosperity and better dental care have lessened a certain kind of pain, but they haven't mitigated a deeper suffering, the spiritual pain of the creature who looks everywhere and finds nothing staring back. 30

Which isn't to say let's renounce prosperity and go back to having our teeth pulled by wooden utensils, God forbid. 31

But it's really to say that rising GDP is not the whole story of modernity.

Here, Jonas joins the company of so many who lived through two world wars followed by the Cold War.

It's not a left-right thing. 32

Here, Jonas joins the company of so many who lived through two world wars followed by the Cold War.

It's not a left-right thing. 32

Which is perhaps why Jonas can be an influence on Leon Kass, who cites him as major thinker of the 20th c. and can sound like a Greenpeace activist skeptical of GMOs, Monsanto, Big Pharma. 33

Jonas, in short, is a kind of naturalist or aspiring naturalist, who sees the writing on the wall of postmodernity. He's a herald of those who would urge caution against growth at all costs, be it on the anticapitalist left or the anticapitalist right. 34

But again the problem isn't capitalism per se. It's an intellectual-spiritual critique, not a materialist one. Materialist critiques are themselves gnostic! 35

In any case, Jonas suggests the possibility that just because we can doesn't mean we should. Boundaries have something to teach us but overcoming all boundaries isn't going to make us feel less alienated. The allure of progress can also be a distraction or an addiction. 36

I suppose this is a highbrow way of saying "There are more things in heaven and Earth, Horatio, / Than are dreamt of in your App Store." 37

Like Heidegger, Jonas thought that technology was a false god, though not necessarily something we could or should resist. The problem is not tech per se, but our motivation for using it, the religious, salvific value we ascribe to it. 38

If the goal is to live a non alienated life, the question is how, where to begin? On this we can be pluralistic without relativistic, but I don't think it means destroying the Fed, google servers, and burning it all down. That kind of binary thinking is itself gnostic. 39

Jonas dared to be more prescriptive than Heidegger. He urged us to consider one categorical constraint, a new imperative. We have to act in such a way that we ensure the possibility of future human life. 40

There's a double meaning here, as human life means not just our biological continuation, but also our ontological continuation.

We shouldn't change our nature, and certainly we shouldn't do it in a way that is irreversable. 41

We shouldn't change our nature, and certainly we shouldn't do it in a way that is irreversable. 41

On what basis can Jonas posit this sense of responsibility without appealing to God or religion? Good question, but he thought he could. Even though when speaking to Jewish audiences he invoked the Biblical anthropological definition of the human as made in a divine image. 42

Another question for Jonas would be how we can know what our nature is.

Another question is this: given that part of our nature is to be creative and to engage in artifice, what ethical boundaries should constrain our creativity? 43

Another question is this: given that part of our nature is to be creative and to engage in artifice, what ethical boundaries should constrain our creativity? 43

I don't know how Jonas would answer these or how he would do so in 2021, but I know that asking the question is already an improvement over taking it for granted that more is better. 44

Kant focused on our responsibility to one another in the sense of not using each other, not instrumentalizing one another, not relating to others as merely objects. Jonas realizes that if you want to realize this "kingdom of ends" you have to also be a steward of nature. 45

We are ecological beings and our habitats have to be protected, not just our "souls." The earth has a claim on us. What does this look like in practice? Reasonable people disagree, but there's definitely an aversion to full fledged transhumanism. 46

There's some appeal in Jonas to the organic. The gnostic knows not of the organic, for life is defined as fundamentally inorganic, awkward. It's all a construct, as it were. 47

Can we settle the debate between the gnostic and the naturalist? Is it even an intellectual one? Idk. Maybe it's a matter of faith or temperment or experience. Gnosticism and naturalism are both just MOODs. 48

Look, Jonas wasn't naive. And nor was Heidegger. They can't just be naturalists 1.0 who reject the modern sense of agency and celebration of creativity. It's about balance. Work for 6 days, but rest for one. Technologize for 6 days, but don't deny you're also a homo ludens. 49

This is the question right now, and, absent religion, absent public reason, it seems quite hard to resolve. But can we all agree that a sense of rest is good, that life isn't just about being on, isn't only about work and accomplishment, hustle, grit? I hope so. 50

Sabbath isn't just a day of the week, it's a state of mind, and in the West it's a vibe we could use more of. Why should a gnostic rest? Law is deception. Ritual is a ruse. There is no way to contact the Alien God. 51

Speaking of alien God, is UFO culture a symptom of gnosticism? Like what's the spiritual urge beneath it, excepting the question of its rationality? 52

If you want to read a great book, I highly recommend @menachemkaiser's brilliant, moving memoir, Plunder. In it, Kaiser excavates the inner world of Nazi treasure hunters, who often have a gnostic sensibility...53

He sees the obsession with treasure as a way of avoiding the elephant in the room, mass death, mass murder, seemingly inexplicable evil, great loss and mourning. Are UFOs a decoy from our misery, a longing for a simulacrum of the God who can save us? I speculate at my peril. 54

Maybe Jonas is just a great sermon, like the rousing speech of the reactionary, Mishima, memorialized in the Paul Schrader film. Maybe he's not actionable, just cautionary. Even so, his critical lens is useful, his hope for human life compelling. 55

Jonas wants us take seriously the concept of the rights of the unborn, the rights of the future ones, to ask ourselves not just what we owe people living today, but what we owe people living in 100 years or even 1000. 56

Again, this isn't about opening up excel and inputting an algorithm, as if there were one. 57

Imagine, though, what might change if we lived with intentionality of this degree rather than just expedience? I'm reluctant to say nothing would be different. 58

Now does Jonas sound kind of trad? Obviously, the naturalism does make him sound like a crank saying "kids these days." But Jonas himself seems to cavort with gnostic sensibilities, so perhaps his whole critique is a self-diagnosis, a reflection of ambivalence. 59

If you read one thing by Jonas, let it be this, "The Concept of God After Auschwitz":

web.ics.purdue.edu/~akantor/readi…

web.ics.purdue.edu/~akantor/readi…

Jonas describes God, by way of Kabbalah, not as a God who condones evil, but as a God who condones human freedom, and who risks the worst of human evils for the sake of granting humanity the gift of ethical responsibility. 61

God makes Godself small relative to human power because God wants to gamble on a world in which we, not God, are the drivers. It's not quite Deism, because God is still here, hiding, but God is here as witness, not as actor. 62

Where was God in the Holocaust? God was in the Gas Chambers, crying out. And God was in the souls of the Nazis, crying out, too. 63

God was crying out Noli Me Tangere, as it were. Don't look to me. Don't ask me why this is happening. Ask yourselves! I want you to stop this. 64

The poet @ilya_poet writes, “At the trial of God, we will ask: why did you allow all this? And the answer will be an echo: why did you allow all this?”

This is exactly the sentiment Jonas is after. God is not omnipotent, but God is omniscient. 65

This is exactly the sentiment Jonas is after. God is not omnipotent, but God is omniscient. 65

When I share this theology with folks, some believers, some not, I get mixed reactions. A lot of people don't like the idea that God is helpless, not in control. Even atheists find it disturbing! 66

It's a common-ish trope in Lurianic Kabbalah, that God is enshackled in the husks of demonic energy, and that we must free God, and ourselves, from the antigravitational pull of the mundane. 67

In fact, it's from Lurianic Kabbalah that the modern ethos of "Tikkun Olam" derives, the notion of spiritual-ethical activism as a form of repairing the world, but repairing God, restoring the divine to the proper place. 68

But guess what? This rendering of God is super gnostic!! 69

God as a prisoner. Check. Human beings as free to choose whatever they want with no real guardrail. Check.

70

70

At the end of the day, Jonas's theology, or theodicy, justifying God in the face of evil, is existentialist or existentialist with an asterisk. 71

Taking a pause until I reach 100, but consider that Jonas's God is not an Alien who stands OUTSIDE of the world, but an Alien who stands INSIDE of the world.

72

72

I suppose the alien in the world is better than the alien beyond it, because if gives the sentiment of discoverability, connection. But responsibility remains with us, in both stories. And it remains lonely. 73

God is in solidarity with us, as it were, but more like a ghost, a memory. Or else, like an aging relative who recognizes us, appreciates our presence, but can't get up to hug us. 74

Ok, so it's pretty sad, but also it's not nothing. It's not the cold atheism of Nietzsche or today's rationalists. It's perhaps more of an ambiguous loss. 75

Ambiguous loss is different from other kinds of loss in that the thing lost is present AND absent, rather than just absent. For example, a soldier comes back after war a changed person. Their return is not the same as the return of the person they once were. 76

Whether you think of God as having a kind of PTSD from the act of creation, or a dementia wrought by history, or simply a midlife crisis as God finds Godself in the Dantean woods, the point of these myths is that choice is not between faith and unfaith. 77

Modern belief is the strained belief of a new relationship to God. Not no relationship and not the relationship that we had before Hobbes, Descartes, Kant, etc. 78

The specific story is less important than the sentiment of ambiguity. To a traditional believer it can sound heretical. 79

Yet at the same time, you can see it as a last ditch effort to save the God that rationalism would simply pronounce dead (prematurely). 80

Some call this idea that God changes, is changed by circumstance, process theology. 81

But process theology itself is not a merely modern idea. The Talmud teaches that lots of things changed after the Temple was destroyed. God manifested in new ways. 82

Now, God is heard as an echo. Prophecy is no longer authoritative. It is, to quote Bava Batra, the province of children and the deranged. 83

Exodus features a God who saves with spectacular miracles, intervenes in political history. The God of the Talmud is one who is bound by vows, in need of human saving (there's a story of Moses nullifying God's vow). 84

Which is just to say that Jonas's theology may be extreme, but he's not new. There's room within tradition for his flipping of the switch between God and humanity. 85

(If you followed the tiktok meme, you know what I'm talking about.) Modernity, which in Jewish thought begins with the Roman-induced Exile initiated a process in which humans become responsible where once God was. A kind of forced spiritual adulthood. 86

What Jonas does is locate the break not in the year 70, but from day 1, from the moment before God says "let there be light." 87

The premise of gnosticism is that God is far, so far, as to be inaccessible.

Jonas's premise, a variation on the form, is that God is near, so near and vulnerable as to be elusive. 88

Jonas's premise, a variation on the form, is that God is near, so near and vulnerable as to be elusive. 88

Which God is to be more feared, more desired? The deus absconditus who responds not to prayer or the divine immanence who shakes when we pray, murmuring Amen, but nothing more? Which is more haunting? 89

Of course, Jonas's myth is speculative. We don't know God to be so far as to be absent or so close as to be ambiguously lost. Rather, we feel it. And sometimes, we feel both, in different moments. And sometimes, it's the God of Exodus again. Orientation is dynamic. 90

And fwiw, Karl Barth embraces the Gnostic myth and the alien God, and opposes Hitler. There's no one way street from gnosticism or anti-gnosticism to political conclusion. 91

Where Jonas and Gnosticism converge is on the point of human responsibility and agency. Both risk a kind of subjectivism. 92

But Jonas saves himself from total subjectivism by insisting that there is a God or a Truth, there is a witness, if one that is in need. 93

To say otherwise is to slide down the slippery slope of letting evil stand. God is here, if only to say, "this is wrong." 94

We can't prove this God, but to insist that everything is a human construct is a symptom of solipsism, not a great discovery. It's a symptom of alienation. 95

But just because there is something real on the other side, doesn't mean we can have certainty as to what it is.

Both Heidegger and Jonas agree that once we are asking whether truth is subjective or objective, we already have a problem.

96

Both Heidegger and Jonas agree that once we are asking whether truth is subjective or objective, we already have a problem.

96

Here's the rub. For Heidegger, the term "Being-in-the-world" is a term of organic unity, preceding subject-object dualism.

For Jonas, Being-in-the-world smacks not of unity, but of alienation. For the world, as he understands Heidegger to be saying is the conventional. 97

For Jonas, Being-in-the-world smacks not of unity, but of alienation. For the world, as he understands Heidegger to be saying is the conventional. 97

To be anti-gnostic one would have to seek to be not just being-in-the-world, but being beyond the world. One would have to reach not just for time, but eternity, not just place, but the Place. (In Hebrew, HaMakom, the Place is one of God's names). 98

Despite his serious critique of Heidegger, Jonas shares with him a sense that modern rationality hasn't delivered on its promise.

Gnosticism may simply describe our condition, even if Jonas sought to go beyond it. His criticisms of existentialism are also self-criticism. 99

Gnosticism may simply describe our condition, even if Jonas sought to go beyond it. His criticisms of existentialism are also self-criticism. 99

They represent the prayer of the reluctant believer, the prayer that someone might hear it, the prayer that in reaching out for a listener, has an answer, an answer that is of itself and beyond it. 100

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh