OK, folks, brace yourselves because here comes the ultimate #BreakfastPaleography thread, in which I will follow the development of the wonderful, magical, mysterious and apparently very flexible letter [g] over the course of more than 2,000 years!

We’ll start in Rome, then jump up to the British Isles before heading back to the Continent. Buckle up, ‘cause here we go!

First up, majuscule [G]. This is the boring part of the story. Ancient Latin epigraphic and numismatic inscriptions form capital [G] in just about the same way we still do. Here’s one from 1st-c. Pompei. There, that was easy! db.edcs.eu/epigr/bilder.p…

Ah, but minuscule (lower case) [g]? That’s a really interesting tale indeed. Some of the earliest examples of lower-case lettering in the Latin alphabet are written in New Roman Cursive, starting in the 3rd c. Here's @BeineckeLibrary P.CtYBR inv. 2125 (Ravenna, 613-641 CE)

Here we see a few different [g]s, but generally it’s an open hook. In ligature, as here, a second stroke makes a crossbar at the top; this will lead us directly to the insular flat-topped [g] in a few centuries.

Speaking of flat-topped [g], let’s head up to Northumbria and Ireland, where things were still hopping in the centuries after the withdrawal of the Romans from Britain. Majuscule [G] shows up in uncial manuscripts like the extraordinary 7th-c. Codex Amiatinus (note the descender)

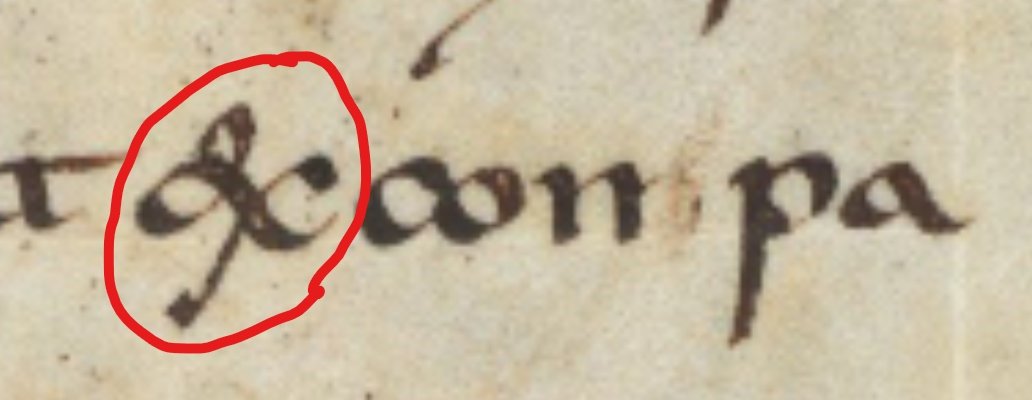

Manuscripts written in Insular minuscule use the flat-topped [g] that will continue to be closely associated with insular scripts, especially in the vernacular (here's St. Gall MS 51, from Ireland: e-codices.unifr.ch/en/csg/0051/8).

Meanwhile, over on the continent, minuscule forms develop into Merovingian, Visigothic, and other pre-Caroline scripts. TBH, it’s a crazypants free-for-all over there. Look at these [g]s! When they’re ligated, things get even more interesting. (l-r: Luxeuil, Corbie, poss. Laon)

OK, settle down, everyone. Here comes the standardization of minuscule script during the reign of Charlemagne (hence “Caroline” script). Looks familiar, right? There’s a direct line from 9th-c. Caroline letterforms to the typeface Twitter uses!

As Caroline slowly morphs into Romanesque in the 11th-c. (or “proto-Gothic” if you prefer), [g] becomes a bit more structured, sometimes with two closed bows, and sometimes with an open lower bowl. Here’s Gottschalk of Lambach, in the late 12th c.

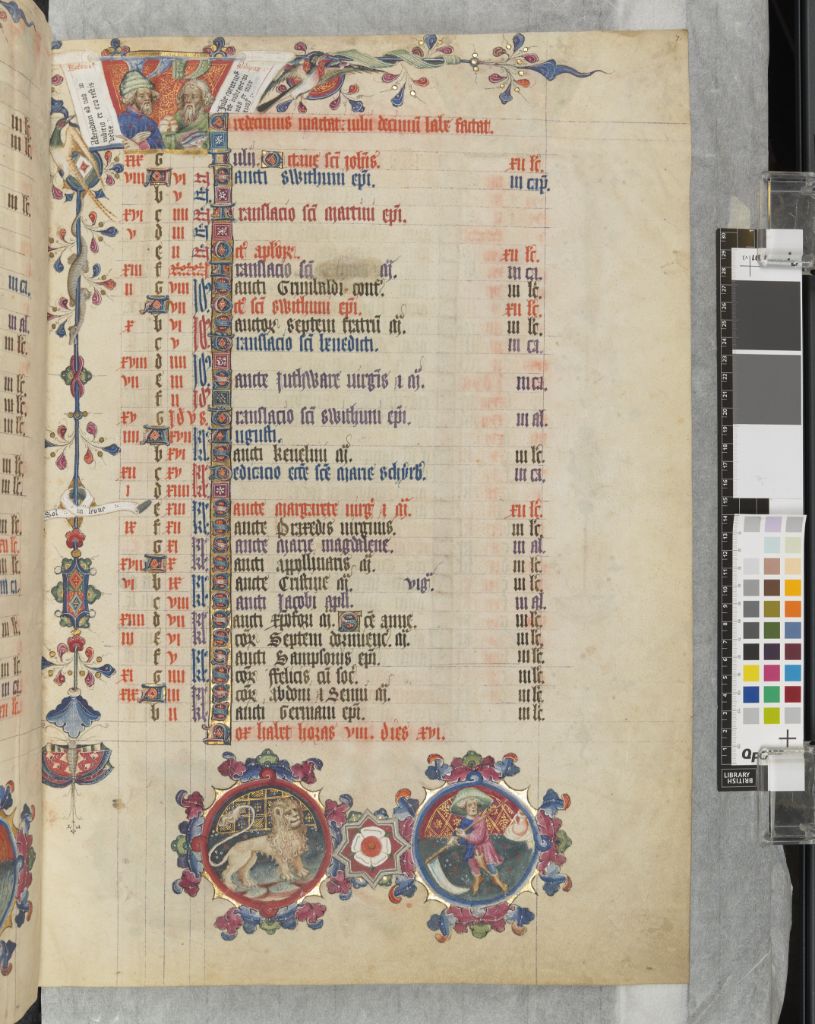

In the early 13th-c., a major aesthetic shift happens in script, just as in architecture. The round vs. angular contrast shows up in script as well. Here’s a Gothic quadrata from 15th-c. France and a bâtarde from the same place and time:

Meanwhile, down south in Italy, dudes like Petrarch and Boccaccio resurrect Caroline models in their own 14th-c. scripts, bringing us back to that rounded, two-compartment [g] that looks an awful lot like the one in this very font!

And that’s the story of the gorgeous, gregarious, glamourous letter [g]. Drop your favorite in the comments! Come back next week and we’ll do [&]!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh