﷽

“We’re seeing reversal of the spheres of the spiritual & sensual. The spirit is vast & free, soaring. The sensual is bound & restricted…”

Now, vastness is attributed to the sensual while restriction is attributed to the spiritual, of detriment to both faith & fitra…

“We’re seeing reversal of the spheres of the spiritual & sensual. The spirit is vast & free, soaring. The sensual is bound & restricted…”

Now, vastness is attributed to the sensual while restriction is attributed to the spiritual, of detriment to both faith & fitra…

“Why has digital entertainment seduced the world? Why have some of the most sublime meanings taken the lewdest of forms? Might it be because the human instinct to find meaning - one that can only be fulfilled through the Divine - grows evermore distant, a figment of imagination?

https://twitter.com/imanmbadawi/status/1488974788777418777

When realities are reversed, we must it #flip_it by reclaiming the Reality.

Find the #meaning in yourself, in all things the meaning will find you.

What bold devils dare steal, brave angels repeal.

What do the words below mean to you?

#think_bigger

Find the #meaning in yourself, in all things the meaning will find you.

What bold devils dare steal, brave angels repeal.

What do the words below mean to you?

#think_bigger

Yes, yes. “How could shaykha quote this?”

My friends, I know everything about every movie my children have ever seen.

As babies, we kept their diapers clean.

As youth, we keep their minds clean.

We’re fighting something way bigger…

God bless mom.

#UpcomingBook

My friends, I know everything about every movie my children have ever seen.

As babies, we kept their diapers clean.

As youth, we keep their minds clean.

We’re fighting something way bigger…

God bless mom.

#UpcomingBook

May Allah’s infinite peace & blessings be upon Rasūlullāh, his pure progeny & folk, along with his gleaming companions, illuminated inheritors and all his loyal followers until the Last Day.

“Who you taught you this?”

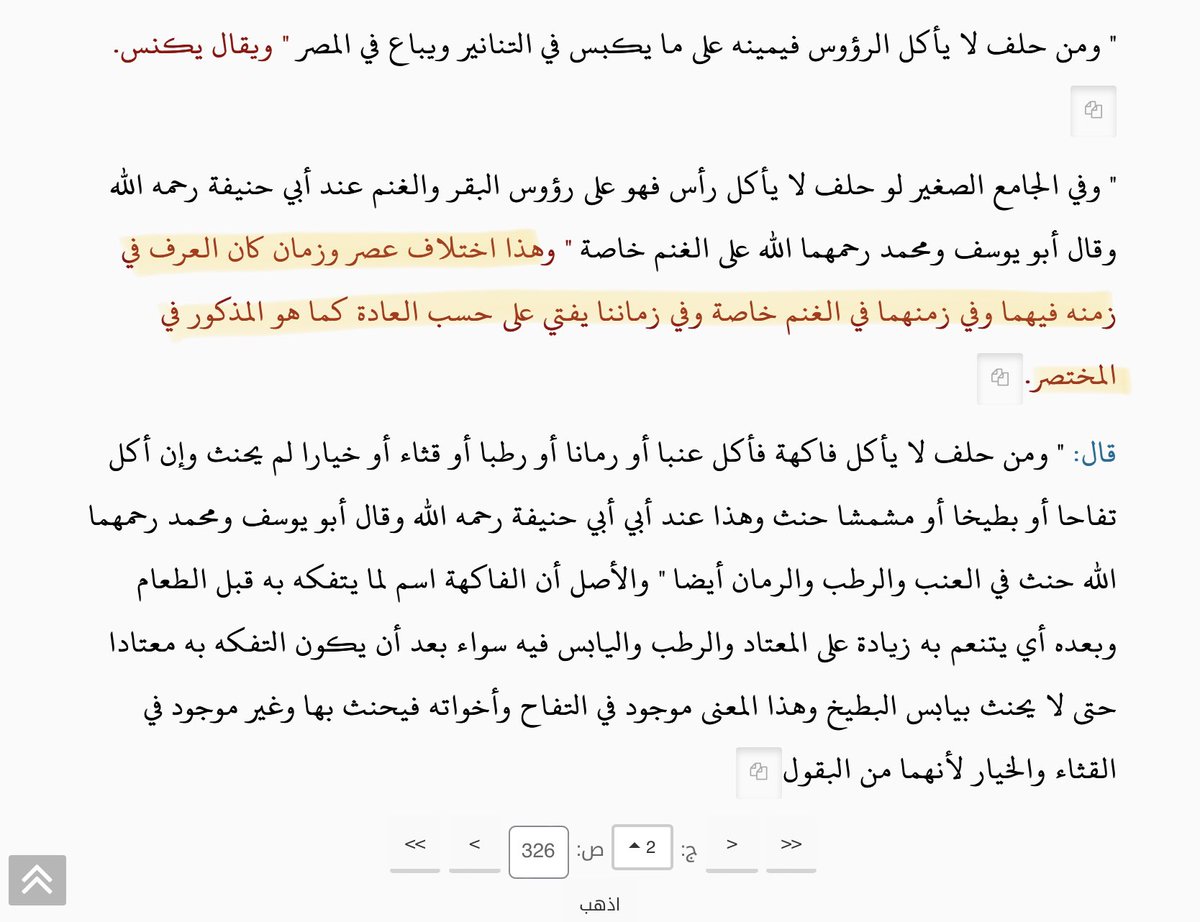

The greatest Imām, Abū Hanīfa

Then, after him, مفتي الثقلين ‘Umar Najm ad-Dīn

Then, after him Imām al-Marghīnānī

Scholar-mom speaks of practice #UpcomingBook

Mom-scholar speaks of theory #metafiqh

رضى الله تعالى عنهم وعنا بهم آمين

The greatest Imām, Abū Hanīfa

Then, after him, مفتي الثقلين ‘Umar Najm ad-Dīn

Then, after him Imām al-Marghīnānī

Scholar-mom speaks of practice #UpcomingBook

Mom-scholar speaks of theory #metafiqh

رضى الله تعالى عنهم وعنا بهم آمين

https://twitter.com/imanmbadawi/status/1436470134902824967

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh