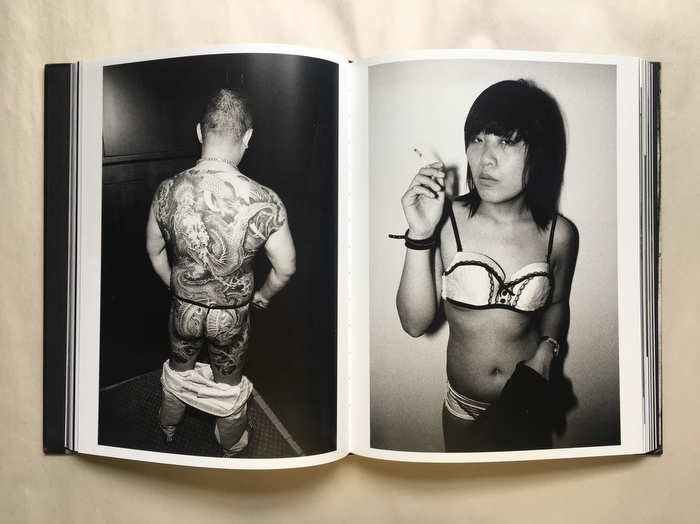

As the twenty-first century began, Japan was entering its second Lost Decade, Europe was culturally moribund, and much of the rest of the world was hostile, so young Americans went to China. They found an authoritarian country freer than their own. I heard that said frequently.

They felt free, whatever that means. This was a time of limited enthusiasm for the American project, especially among people in their early twenties. For the dropouts burning a year teaching English, one of the alternatives to going to China was going to Afghanistan.

Already, I think they had a sense that their future was being foreclosed. Some were wealthy enough that it didn't matter. If many of those millennial Americans had seeded in their already fertile skepticism some suspicion of liberal democracy itself, most probably recovered.

These are Rian Dundon's pictures from Changsha. I know I have another edition of the book stuffed in a box on Vancouver Island, but I ordered a copy of one of the books rediscovered in a French storage space: jetagebooks.net/portfolio/chan…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh