The #RwandanGenocide began 28 years ago.

April 7 1994.

One of the worst events in human history.

And one that looms large in my aid-worker family’s psyche

THREAD…with very distressing images

#Kwibuka28 #Rwanda #Genocide #GenocideAgainstTutsi

April 7 1994.

One of the worst events in human history.

And one that looms large in my aid-worker family’s psyche

THREAD…with very distressing images

#Kwibuka28 #Rwanda #Genocide #GenocideAgainstTutsi

I was home from university for the Easter holidays when the massacres began and I remember my parents and I being transfixed by the news.

They’d been aid-workers for decades.

Dad was with the UN’s refugee agency.

Mum, a child psychologist, worked with child soldiers.

They’d been aid-workers for decades.

Dad was with the UN’s refugee agency.

Mum, a child psychologist, worked with child soldiers.

Neither were naïve about the world’s darker corners, but the speed and scale of the savagery in Rwanda left everyone reeling.

Over the next 100 days, an estimated 800,000 Tutsi were hacked to death with machetes wielded by their Hutu countrymen.

House by house. Village by village. Town by town.

Often it was neighbour killing neighbour.

Occasionally, family members butchered their own kin.

House by house. Village by village. Town by town.

Often it was neighbour killing neighbour.

Occasionally, family members butchered their own kin.

Two pieces of footage from those days remain in my mind.

One was shot clandestinely, from someone hiding in some bushes.

It showed a makeshift road-block with a few Tutsi cowering on the ground as a mob of Hutu, high on bloodlust circled and yawped and brayed around them.

One was shot clandestinely, from someone hiding in some bushes.

It showed a makeshift road-block with a few Tutsi cowering on the ground as a mob of Hutu, high on bloodlust circled and yawped and brayed around them.

As the axes rained down one of the men put his hands up, an instinctive yet hopeless bid to protect himself.

His hands were shredded before his skull was split.

His hands were shredded before his skull was split.

Another was filmed from a car as it drove down a street lined with bodies, all bearing deep, angry axe wounds.

It is hard, thirsty work, chopping up a human being, so the killers would make a few strategic hacks and leave the person to bleed out, in agony, sometimes for days.

It is hard, thirsty work, chopping up a human being, so the killers would make a few strategic hacks and leave the person to bleed out, in agony, sometimes for days.

The Hutu achieved a death-rate three times more rapid than that of the Nazi’s with their technologically advanced killing chambers.

The planning that had gone into the genocide was immediately apparent.

Within hours of the President’s plane being shot down on April 6, senior Tutsi were being rounded up, the stockpiles of machetes released to the hounds and the local radio broadcasting calls to massacre.

Within hours of the President’s plane being shot down on April 6, senior Tutsi were being rounded up, the stockpiles of machetes released to the hounds and the local radio broadcasting calls to massacre.

In the months leading up to the slaughter, Romeo Dalliare, the Canadian General in charge of the hopelessly under-manned force of UN peacekeepers in the country at the time, had warned of just this.

An informant had given him the precise details of how the genocide was to unfold.

Where the weapons were kept.

Who was doing the training.

Who was compiling lists of “cockroaches” to be eradicated.

Where the weapons were kept.

Who was doing the training.

Who was compiling lists of “cockroaches” to be eradicated.

Dallaire sent message after frantic, exasperated message to the UN in New York, pleading for a mandate to raid the weapons caches.

The UN Secretary Boutros Boutros Ghali had no interest in Dallaire’s SOS.

A few years earlier, as Egyptian Foreign Minister he’d overseen an arms sale to Rwanda.

A few years earlier, as Egyptian Foreign Minister he’d overseen an arms sale to Rwanda.

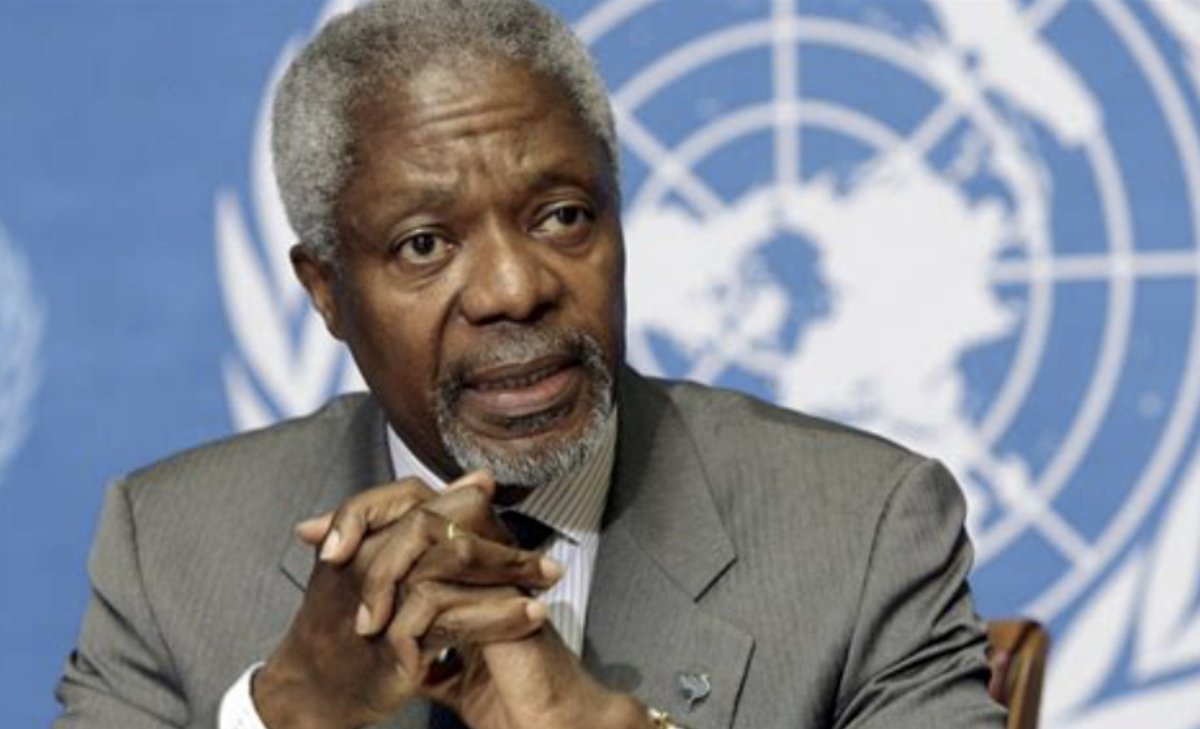

Neither did the Ghanaian man in charge of Peacekeeping at the time, the future Secretary General Kofi Anan.

Their response to Dallaire’s requests for permission to stop the genocide was always the same.

No.

No, No, No and No again.

These are the same people who bleat the ‘Never Again’ platitude whenever the Holocaust is mentioned.

No.

No, No, No and No again.

These are the same people who bleat the ‘Never Again’ platitude whenever the Holocaust is mentioned.

Within weeks of the genocide starting, the UN Security Council actually voted to remove the tiny peacekeeping force.

Dallaire had asked for a few thousand extra troops to halt the massacres.

Instead, he was ordered out and the UN presence was reduced from 2500 to 300.

Dallaire had asked for a few thousand extra troops to halt the massacres.

Instead, he was ordered out and the UN presence was reduced from 2500 to 300.

Incredulous, a few hundred soldiers, mainly from Ghana, Senegal, Tunisia, Bangladesh and Canada, Dallaire included, stayed.

By staying in an effort to protect civilian life, they were disobeying orders.

The UN reminded Dallaire he had no mandate to protect people.

By staying in an effort to protect civilian life, they were disobeying orders.

The UN reminded Dallaire he had no mandate to protect people.

Nor could they do very much by staying.

They couldn’t offer food, water or shelter.

They could only play a giant game of bluff with the genocidaires, count on them not knowing that they weren’t armed and that the world wouldn’t have cared if they been hacked up too.

They couldn’t offer food, water or shelter.

They could only play a giant game of bluff with the genocidaires, count on them not knowing that they weren’t armed and that the world wouldn’t have cared if they been hacked up too.

The peacekeepers only managed to save a few thousand people — a small victory as the bodies piled up in their thousands, then in their tens of thousands, and then in their hundreds of thousands.

By the time it was over, 70 percent of the country’s Tutsi population lay dead.

By the time it was over, 70 percent of the country’s Tutsi population lay dead.

All they knew is that they couldn’t leave.

And it mattered, that they knew that, that those individual men did not fail as human beings when so many others did.

And it mattered, that they knew that, that those individual men did not fail as human beings when so many others did.

But to many, the price of this heroism was intolerably high.

The Senegalese soldier Captain Mbaye – personally credited with using he considerable charm to save hundreds of lives - was one of fifteen UN Peacekeepers who lost their lives.

bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-…

The Senegalese soldier Captain Mbaye – personally credited with using he considerable charm to save hundreds of lives - was one of fifteen UN Peacekeepers who lost their lives.

bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-…

Dalliare, abandoned in hell, the commander, unable to command, let alone protect, developed severe post-traumatic stress disorder.

He self-harmed, became reckless, drove maniacally through checkpoints, taunted death, stormed up to the genocidaires, daring them to kill him.

He self-harmed, became reckless, drove maniacally through checkpoints, taunted death, stormed up to the genocidaires, daring them to kill him.

They describe it as a moral wound, the havoc done to a warrior’s psyche when they are not allowed to fight and repel evil.

Back home in Canada, the ghosts of Rwanda began to follow him through his waking day.

To sufferers of PTSD, the apparitions can appear more real than anything else.

They would surround Dallaire, touching him, reproaching him, the smell of their rotting corpses infecting the air he breathed, driving him insane.

They would surround Dallaire, touching him, reproaching him, the smell of their rotting corpses infecting the air he breathed, driving him insane.

To sufferers of PTSD, the apparitions can appear more real than anything else.

They would surround Dallaire, touching him, reproaching him, the smell of their rotting corpses infecting the air he breathed, driving him insane.

They would surround Dallaire, touching him, reproaching him, the smell of their rotting corpses infecting the air he breathed, driving him insane.

That didn’t work either, so he tried to overdose.

When that failed he started slashing into his arms, hoping the physical pain might overwhelm the emotional agony.

When that failed he started slashing into his arms, hoping the physical pain might overwhelm the emotional agony.

At his lowest he was found passed out drunk on a park bench, still somehow believing the genocide was his fault.

In his wretched despair, Dallaire has finally understood that he would never be free of Rwanda. That he would never feel sane or normal or safe again.

In his wretched despair, Dallaire has finally understood that he would never be free of Rwanda. That he would never feel sane or normal or safe again.

Dallaire was under no illusions about what they had faced in Rwanda.

“I know there is a God,” he said. “Because in Rwanda I shook hands with the devil. I have seen him, I have smelled him and I have touched him. I know the devil exists and therefore I know there is a God”.

“I know there is a God,” he said. “Because in Rwanda I shook hands with the devil. I have seen him, I have smelled him and I have touched him. I know the devil exists and therefore I know there is a God”.

Dallaire said that when he had to shake the hands of senior members of the Interahamwe, the group orchestrating the killing, they were cold, but not cold as in not warm, cold as in of a different form.

But if the Devil was loose in Rwanda, what, then, does that make Dallaire and his men?

A light shining in the darkness, that the darkness could never understand?

To me, the peacekeepers stand is one of the great moral stands in history; Dallaire a moral Titan.

A light shining in the darkness, that the darkness could never understand?

To me, the peacekeepers stand is one of the great moral stands in history; Dallaire a moral Titan.

My family was torn at by this evil.

Dad went in August 1994.

Tutsi rebels had invaded from Uganda, stopping the massacres and driving the Hutu out.

A tsunami of around two million refugees now fled to what was then Zaire, since renamed the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Dad went in August 1994.

Tutsi rebels had invaded from Uganda, stopping the massacres and driving the Hutu out.

A tsunami of around two million refugees now fled to what was then Zaire, since renamed the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Dad was sent to assist with the relief operation for these refugees.

He came back six weeks later, vacant and shell-shocked.

He would avoid questions about what he had seen, answering with details about the flora and fauna of what seemed a very beautiful land.

He came back six weeks later, vacant and shell-shocked.

He would avoid questions about what he had seen, answering with details about the flora and fauna of what seemed a very beautiful land.

Then one night, at about 1am, he woke up and came down to the living room where I was still up watching TV.

He poured himself a whisky, sat down and started talking.

He had woken from a nightmare, as he did most nights, of my sisters and I being raped and murdered.

He poured himself a whisky, sat down and started talking.

He had woken from a nightmare, as he did most nights, of my sisters and I being raped and murdered.

Unfathomable numbers of women and girls had been gang-raped before they were hacked up.

Dad said their decomposing bodies littered the countryside.

Corpses on their backs, leg spread, with rotting knickers around their ankles.

Dad said their decomposing bodies littered the countryside.

Corpses on their backs, leg spread, with rotting knickers around their ankles.

Mum went a few months later.

The night she came back I stayed up with her into the early hours of the morning as she drank herself into a state of utter despair, recounting what she had seen.

The night she came back I stayed up with her into the early hours of the morning as she drank herself into a state of utter despair, recounting what she had seen.

A visit to a church at Ntarama.

About 5000 Tutsi men, women and children had been hiding there when the gangs attacked, breaking down the doors with grenades.

About 5000 Tutsi men, women and children had been hiding there when the gangs attacked, breaking down the doors with grenades.

The site has been cleaned up now, the skeletons picked of their flesh, neatly arranged for observation, an obligatory stop for genocide tourists.

When Mum visited, the bodies lay where they fell.

A mass of entwined, agonized, putrefying corpses.

She said the stench was palpable from a distance, the evil hanging like a thick, menacing fog.

A mass of entwined, agonized, putrefying corpses.

She said the stench was palpable from a distance, the evil hanging like a thick, menacing fog.

Two children she had met stuck in her mind.

Both were about 12.

Both were now orphans, their extended families butchered.

Both were about 12.

Both were now orphans, their extended families butchered.

The boy had a vast, gnarled scar at the base of his neck where the Interahamwe had tried to hack his head off.

The girl’s face was split in two.

She had taken a machete hit right across it that had split her skull, but not killed her.

It had healed, but lopsided, with deep ridge right across it.

She had taken a machete hit right across it that had split her skull, but not killed her.

It had healed, but lopsided, with deep ridge right across it.

“She will have to live with that face all her life,” Mum sobbed. “Every time she looks at herself she will be reminded.”

Mum returned to the girl’s plight again and again, both that night as she got drunker and drunker, and over the long, drunken years ahead.

Mum returned to the girl’s plight again and again, both that night as she got drunker and drunker, and over the long, drunken years ahead.

It featured when she made her first suicide bid a year later.

She’d gotten blind drunk and climbed into a manhole in the corner of our garden.

One of my little sisters found her when she woke in the early hours to mumbling and wailing coming from outside.

She’d gotten blind drunk and climbed into a manhole in the corner of our garden.

One of my little sisters found her when she woke in the early hours to mumbling and wailing coming from outside.

She and my Dad pulled her out, naked and blathering and sobbing.

Mum vomited all over my little sister as she emerged, crying about ‘Marie’.

Mum vomited all over my little sister as she emerged, crying about ‘Marie’.

“Who is Marie?” my sister asked.

“Marie!”, my mother responded, irritated that my sister didn’t understand. “The girl in Rwanda! Marie!”

My sister took the echo of ‘Marie” and the smell of my Mum’s vomit into the exams she sat later that day.

“Marie!”, my mother responded, irritated that my sister didn’t understand. “The girl in Rwanda! Marie!”

My sister took the echo of ‘Marie” and the smell of my Mum’s vomit into the exams she sat later that day.

The genocide featured when my Mother made another suicide attempt ten years later.

None of the organisations my parents worked for offered any kind of psychological help to their employees, but the doctors who admitted her quickly diagnosed untreated PTSD from Rwanda.

None of the organisations my parents worked for offered any kind of psychological help to their employees, but the doctors who admitted her quickly diagnosed untreated PTSD from Rwanda.

Like so many, my parents couldn’t process the evil they encountered in Rwanda, because if evil is real, then what?

And they didn’t spare their children, my mother in particular.

Rwanda and her work became a regular topic of conversation.

Stories of obscene violence from the worse parts of the world became routine for her children, a normal backdrop to family life.

Rwanda and her work became a regular topic of conversation.

Stories of obscene violence from the worse parts of the world became routine for her children, a normal backdrop to family life.

She never asked us how we felt hearing about it all. Neither did my father. Both were too busy thinking about other people’s children.

And, yes, I know we are more fortunate than these children.

Unimaginably more fortunate.

The End

And, yes, I know we are more fortunate than these children.

Unimaginably more fortunate.

The End

A thread related to the massacre at the church in Ntarama:

https://twitter.com/EdwinMusoni/status/1512813757273186307

Another thread on Daillare's plight, with interviews from people working with him at the time:

https://twitter.com/evohopp/status/1514593392021417987

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh