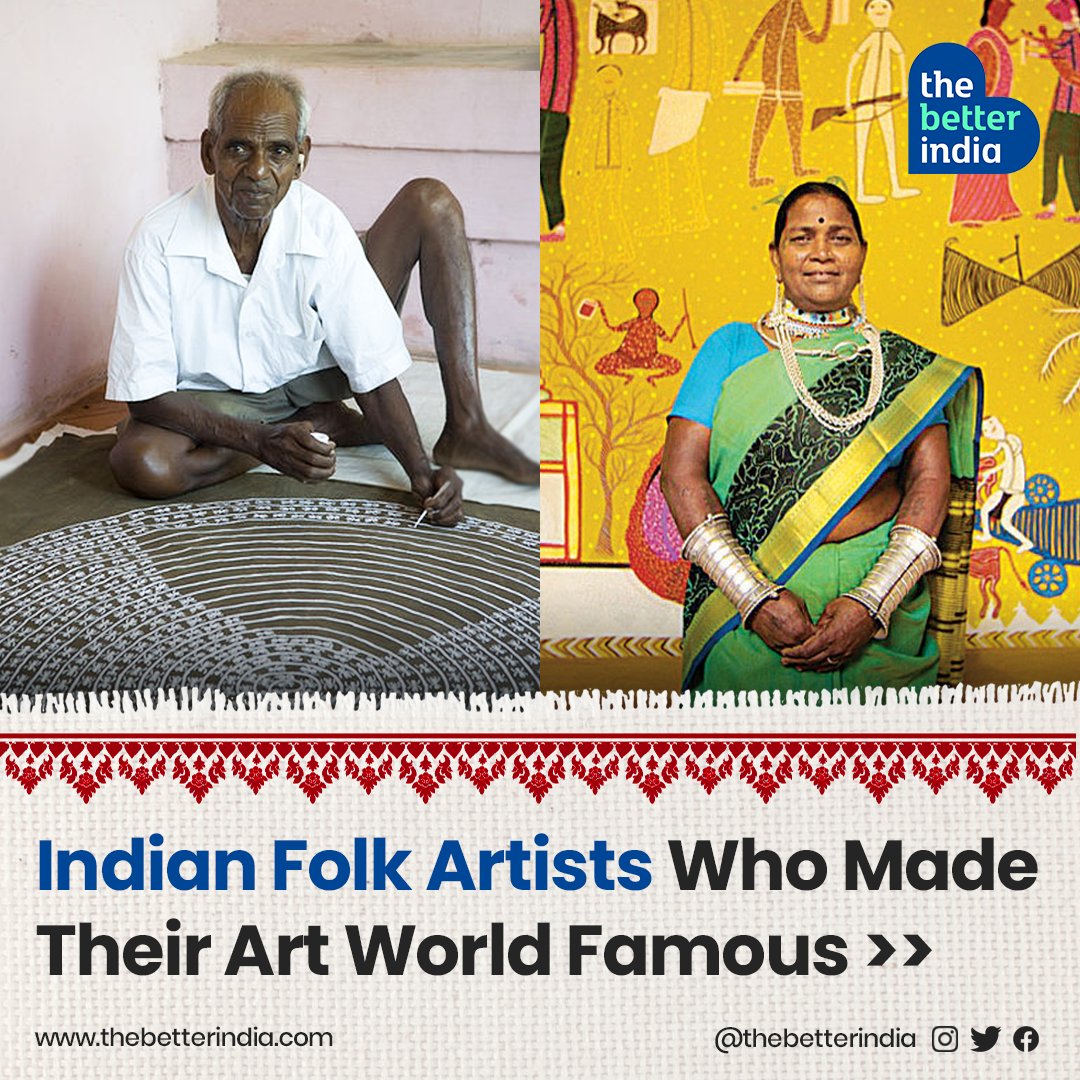

India has a rich legacy of folk art that has been passed down through generations. And many of them are still alive thanks to these pioneering #artists who've toiled tirelessly for their preservation >>>

#IndianArt #FolkArtists #Legends #IndianHeritage #Art #Culture #India

#IndianArt #FolkArtists #Legends #IndianHeritage #Art #Culture #India

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh