A very interesting paper from Dr. Mark Davis’ group shows that in response to the mRNA vaccine, CD8 T cell responses are attenuated in people who had prior COVID compared to uninfected people. What does this mean? (1/)

doi.org/10.1016/j.immu…

doi.org/10.1016/j.immu…

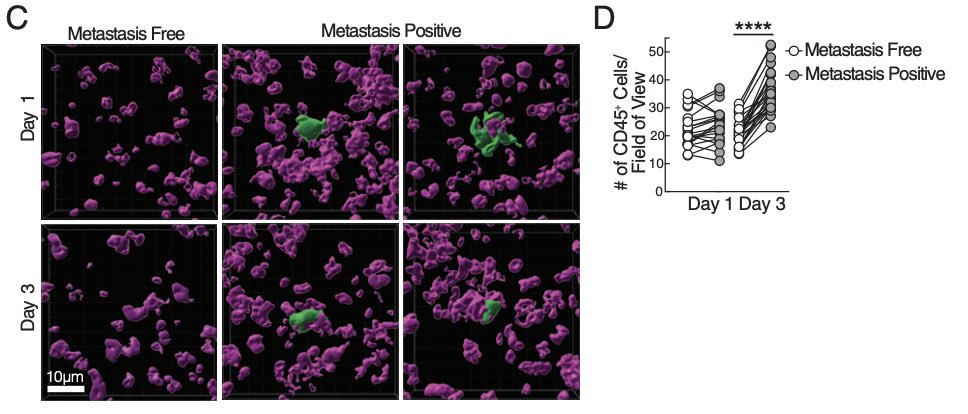

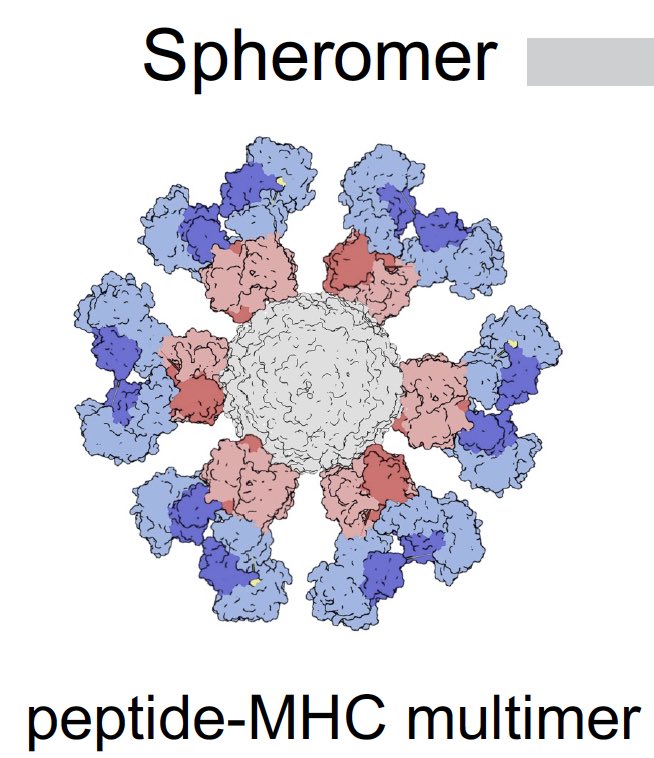

Fei Gao, @VMallajosyula et al used SARS-CoV-2 pMHC-spheromers to detect viral antigen-specific CD8 and CD4 T cells from people who were vaccinated, infected or both. Spheromers are peptide-MHC multimers (12 units) that are more sensitive than conventional pMHC tetramers. (2/)

CD8 T cell responses to viral antigens were compared in people who received the mRNA vaccines to those with prior infection with SARS-CoV-2. The vaccine induced significantly better CD8 T cell immunity in both quantity and quality than the infection. (3/)

Notably, people who recovered from COVID and then were vaccinated had much lower CD8 T cell response than people who were not infected (naive) and vaccinated. The CD8 T cells’ ability to secrete cytokines and become activated was also poorer in the recovered group. (4/)

Why does infection induce poorer CD8 T cell immunity than the vaccine? The answer may be related to the ability of this virus to impair MHC I presentation (5/)

pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pn…

pnas.org/doi/full/10.10…

nature.com/articles/s4146…

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35547852/

pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pn…

pnas.org/doi/full/10.10…

nature.com/articles/s4146…

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35547852/

Why does prior infection impair CD8 T cell responses induced by the mRNA vaccine? This may imply induction of some form of regulatory immune response by the infection, or sequestration of Spike by preexisting antibodies for MHC I presentation. (6/)

Does this mean that prior infection with COVID will render people susceptible to future reinfections? Not necessarily. We know that prior infection promotes better neutralizing antibody responses after vaccination - the best correlate of protection. (7/)

nature.com/articles/s4158…

nature.com/articles/s4158…

Does the study by Gao et al mean that prior COVID will make people immunodeficient (unable to fight any infection)? Not likely based on other data. @JohngLab found enhanced (not lower) immunity to flu vaccine in men who recovered from mild COVID. (8/)

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36599369/

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36599369/

Could impaired CD8 T cell immunity lead to long COVID? Possibly - by enabling the SARS-CoV-2 infection to persist or by enabling reinfections to be more productive. But this hypothesis must be tested. A great paper with much to think about. (End)

Oops, wrong handle! @TsangLab 👆🏼 Sorry!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh