Some thoughts on the NDS Commission report & the South China Sea:

As most folks interested in national security issues are aware, the NDS Commission recently released an assessment of renewed great power competition and the state of the U.S. military. usip.org/sites/default/…

As most folks interested in national security issues are aware, the NDS Commission recently released an assessment of renewed great power competition and the state of the U.S. military. usip.org/sites/default/…

The headline of the analysis was one of grave concern, that: “America’s military superiority—the hard-power backbone of its global influence and national security—has eroded to a dangerous degree.” washingtonpost.com/world/national…

As sure as the sun rises, from predictable places arose a chorus of retort, accusing the report’s authors of focusing too much on military spending to the detriment of other priorities, or of threat inflation on behalf of the "Military Industrial Complex". nationalinterest.org/feature/proble…

In some cases these critics cast aside any pretense to objectivity, putting forward as their opening argument that the NDS Commission experts are defense-industry shills who could not possibly have arrived at their conclusions through honest assessment. pogo.org/analysis/2018/…

Side note: when I see a writer open w/ ad hominem attacks rather than by presenting the merits of the case, I see a warning flag: arguments to follow will likely be weak. Also note: these writers pay their own bills via employment at organizations which also have biases/agendas.

In any case, a specific example of great power challenges in the NDSC report is the eroding mil balance the U.S./allies face in the South China Sea, one of the world’s most vital seaways.

I won’t bore you with the amount of trade, oil, etc. that passes through it, but will rather get straight to an exposition on how much, and how rapidly, the military balance there has eroded over just the last 10 years, and how much it’s likely to further change in the future.

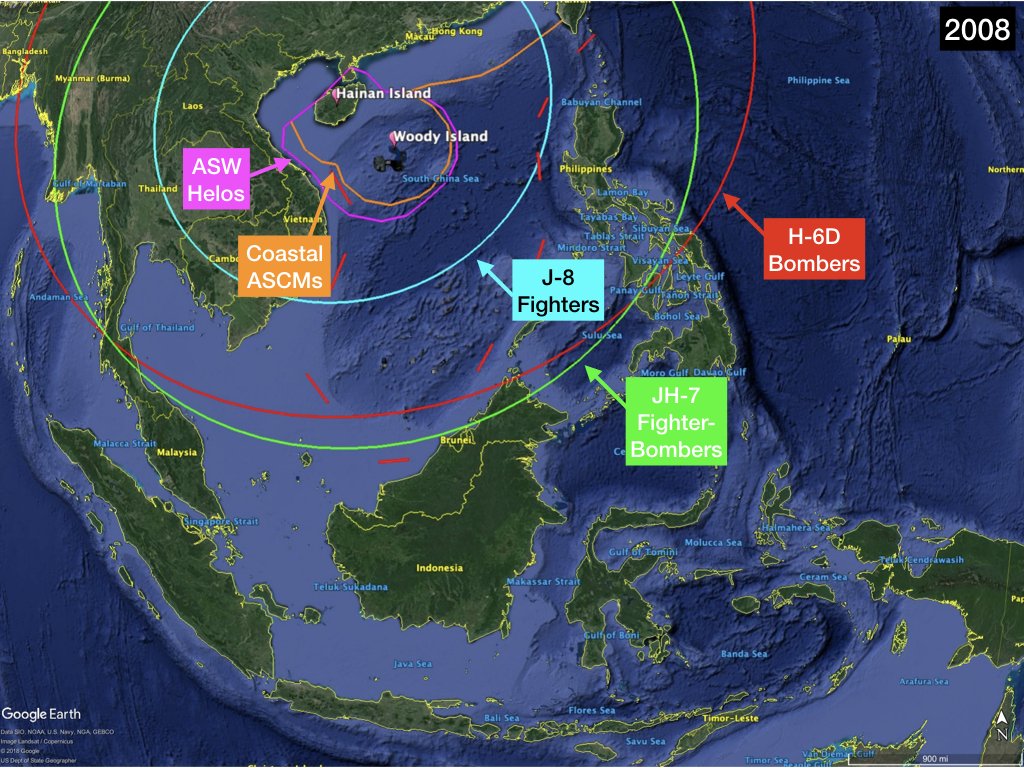

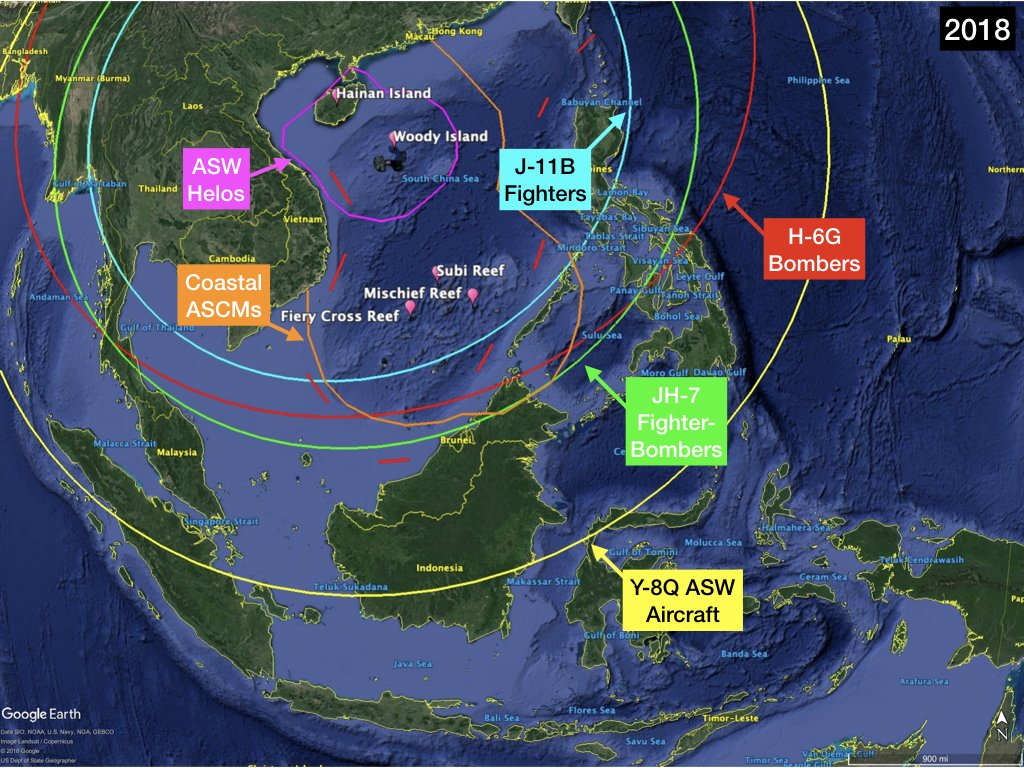

In 2008, China’s ability to exert control over much of the SCS was limited. Cruise-missile carrying aircraft like JH-7 fighter-bombers & H-6D bombers could theoretically roam over a fair bit of it, but would be unsupported at longer ranges by fighters they’d need to escort them.

China’s ASW capabilities were limited, with no real fixed-wing capability and a few helicopters that could only safely operate in the vicinity of Hainan island, perhaps venturing into the nearby Paracels. Coastal anti-ship cruise missile coverage would’ve been similarly limited.

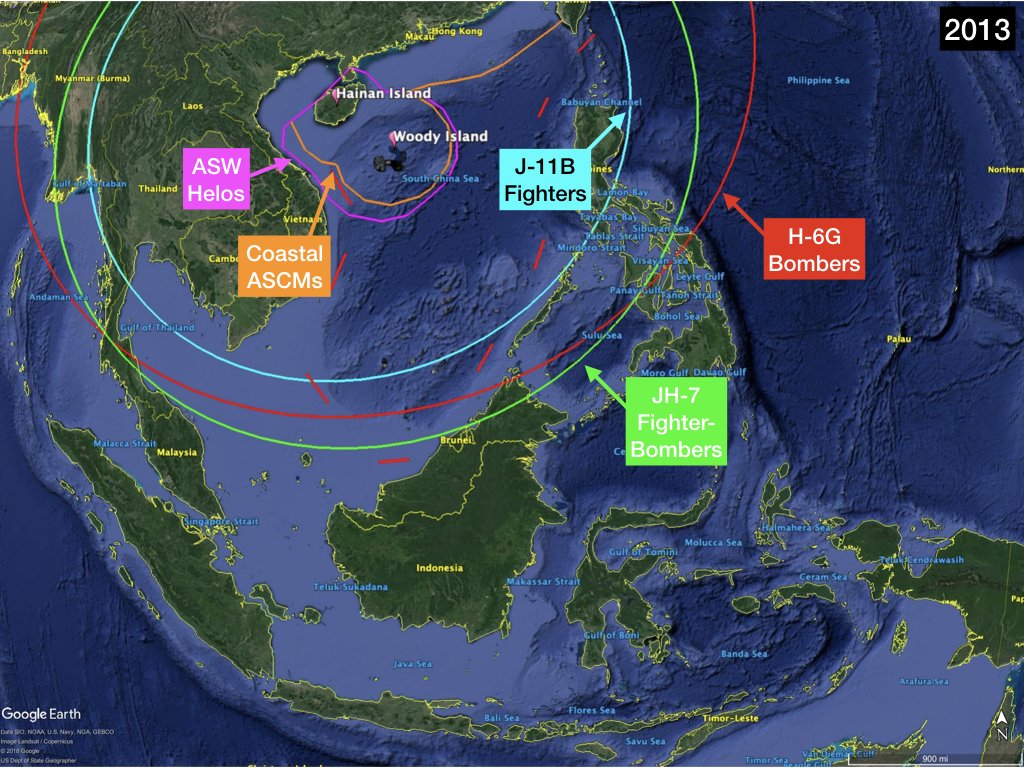

By 2013, China had upgraded its fighter aircraft in the region to J-11B Flankers, which could range further into the central SCS to support strike aircraft. But the southern portion of the claimed Nine Dash Line remained beyond their reach, as well as the Sulu and Celebes Seas...

...where U.S. carriers could likely operate with relative impunity, projecting combat power into the SCS during a crisis. And U.S. submarines could still have operated fairly unmolested over the vast majority of the region.

As the most casual observer will recall, from 2013 to now has been eventful in the region, with China building fully-fledged air bases on huge artificial islands made of material dredged up from the sea floor - and doing enormous environmental damage. warontherocks.com/2016/09/chinas…

Though the islands’ facilities still seem to be under construction, China has already sent long range anti-air/anti-ship cruise missile (ASCM) units to them, in addition to permanent shorter-range air and missile defenses that grace each of their corners. thediplomat.com/2018/05/china-…

In 2017, China deployed a number of new long-range fixed-wing ASW aircraft to the region, with a number spotted operating out of Hainan Island. Similar to strike aircraft, these would be unlikely to venture far from the protection of friendly fighters. defensenews.com/space/2017/06/…

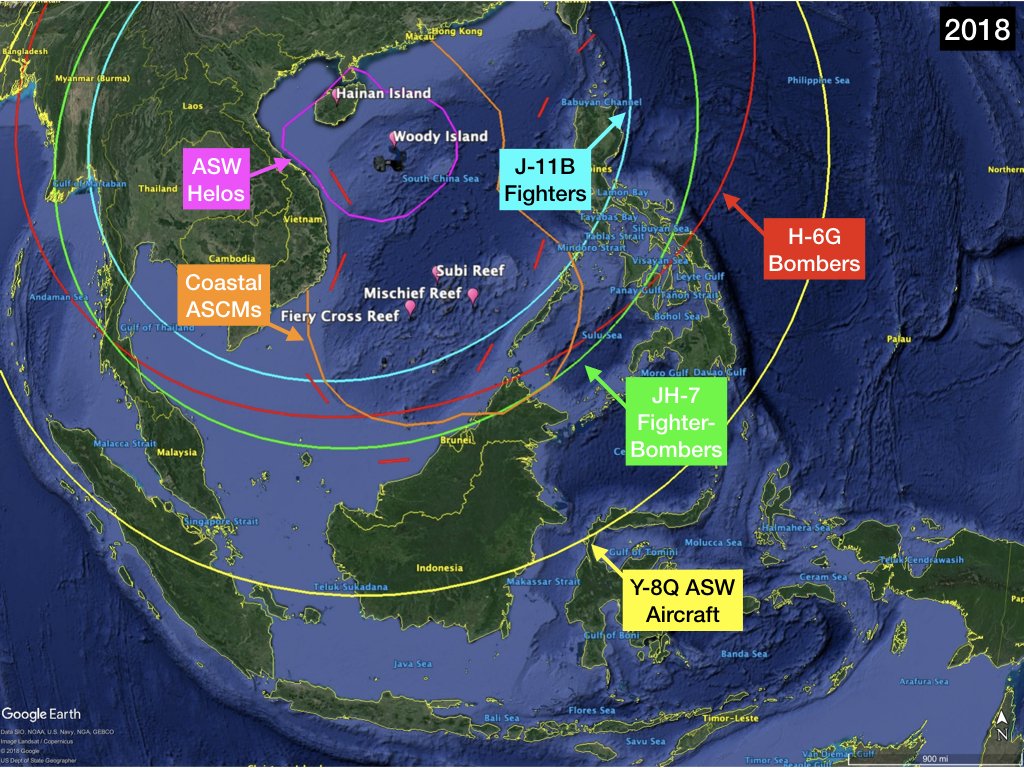

In overview, since China has yet to deploy aircraft to the island bases, it would seem the biggest changes through 2018 are ASCM coverage of most of the Nine Dash Line's area, as well as fixed-wing ASW patrol coverage over far more of the SCS.

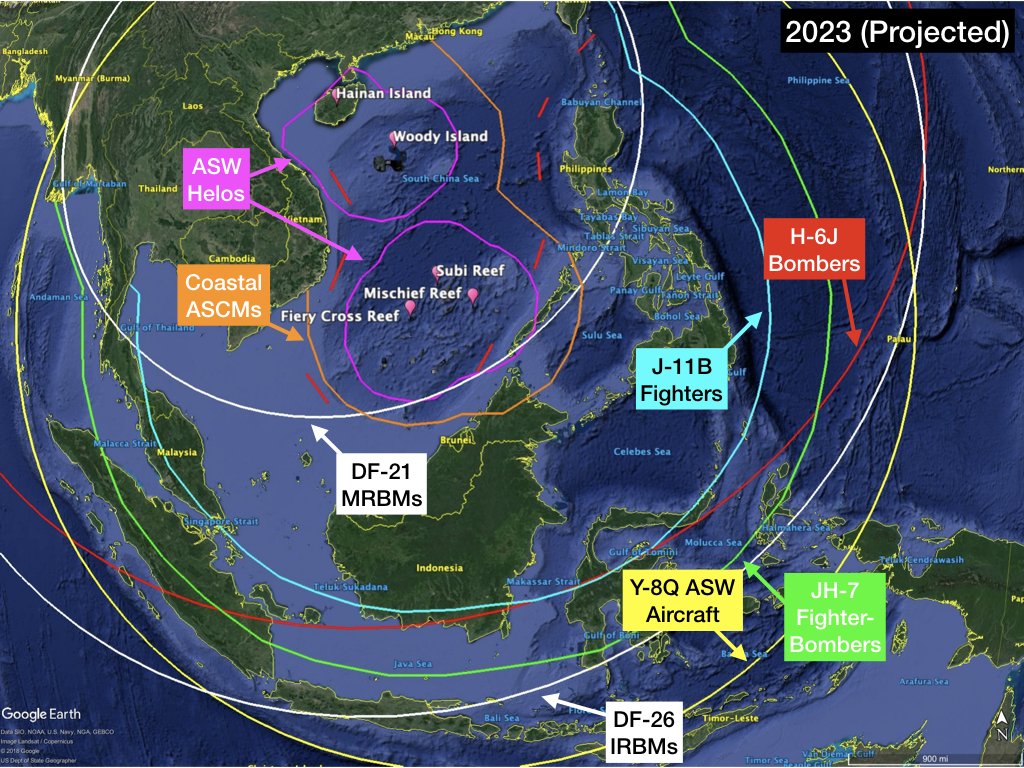

It's in the future that the biggest changes are likely to come to fruition, and most significantly alter the military balance in the region. First, commercial satellite imagery this year revealed the construction of what seems likely to be a base for ballistic missile units...

...of China’s PLA Rocket Force. While it’s too early to know what types will be deployed there, given the heavily maritime nature of the theater my money would definitely be on anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM) versions of the DF-21 MRBM and DF-26 IRBM.

shephardmedia.com/news/defence-n…

shephardmedia.com/news/defence-n…

Also, this year saw the beginnings of deployment of a heavily modernized version of China’s H-6 maritime strike bomber, promising far greater range and carriage of roughly three times the number of anti-ship missiles, in this case likely the deadly YJ-12.

thediplomat.com/2018/10/chinas…

thediplomat.com/2018/10/chinas…

Finally, the next few years likely see the completion of construction of China’s island air bases. And while opinions vary on whether we'll see permanent basing of aircraft, I consider that outcome to be highly likely given the scale of facilities on them. spatialsource.com.au/gis-data/satel…

As a granular example, see these air conditioning units installed on every one of the 24 fighter-size hangars on each island, which tells me they are likely to someday house aircraft which will need to stay out of the humid air if kept there on a permanent basis.

Putting it all together, on current trajectory over, say, the next five or so years, I’d expect we will see maritime strike and ASW aircraft that can range throughout the South China, Sulu and Celebes Seas, all the way to Singapore - and all within Chinese fighter coverage.

...We can also expect ASBMs to be able to threaten any U.S./allied aircraft operating through most of the SCS (via DF-21s), and perhaps even DF-26 missile coverage well out into the Java Sea.

Bear in mind none of this even starts to consider the huge increase in capability the Chinese Navy is undergoing, with its first aircraft carriers going into service at the same time large numbers of modern & capable surface ships are being brought in. nytimes.com/2018/08/29/wor…

So, while some may debate whether China’s intentions are really aggressive, whether “a bunch of rocks” in the SCS are worth fighting for, or if the U.S. still has sufficient military advantage to deter conflict, what one can see through this progression (click through) is that...

...there has been a near-indisputable increase in Chinese military capabilities in the SCS, one that significantly erodes the U.S. military advantage in just the manner described in the NDSC Report.

Note: South Sea Fleet unit dispositions sourced mostly from IISS’s 2008/2013/2018 Military Balance. Aircraft & missile ranges sourced mostly from Janes’ IHS, as well as other open sources. All opinions mine alone & do not represent those of U.S. Navy, DoD, or the U.S. Government.

* DF-21/26 ASBMs threaten U.S./allied aircraft _carriers_, not aircraft

Note: DF-21/26 ASBMs threaten U.S./allied aircraft *carriers*, not aircraft

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh