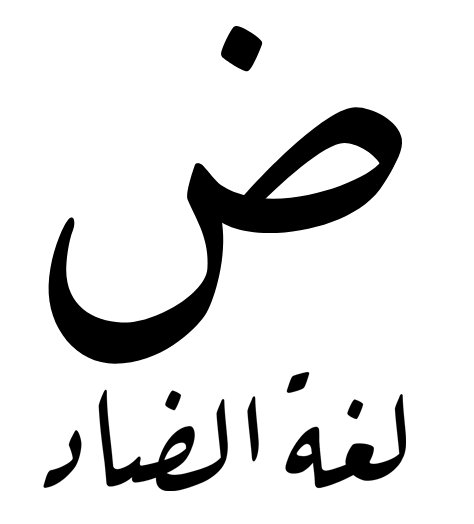

Arabic is often called Luġat al-Ḍād "the language of the Ḍād". Clearly indicating that this language was considered unique specifically for its pronunciation of this letter. But how was it actually pronounced?

In Modern Standard Arabic, it is artificially assigned the pronunciation of a voiced dental pharyngealized stop [dˤ]; This sound is not that exotic, Many Berber and Songhay languages, for example, use it too. So 'lughat al-Ḍād' wouldn't make much sense.

The earliest articulatory description of the ḍād can be found in the first grammar of Arabic, al-Kitāb "the book" by Sībawayhi (died somewhere around 170-193 AH/789-809 CE).

He describes, place and manner of articulation, as well as the air stream mechanism of each Arabic sound.

He describes, place and manner of articulation, as well as the air stream mechanism of each Arabic sound.

Anyone familiar with articulatory phonetics will be struck just how far ahead of his time Sībawayh was with this type of description deconstructing the articulatory elements that make up a sound. It took western linguistics over a millennium to get on his level.

Sībawayh starts off with a long list of the places of articulations (maḫraǧ literally 'place of emitting', or muḫraǧ 'what is emitted') starting from the back to the front he groups together the following consonants.

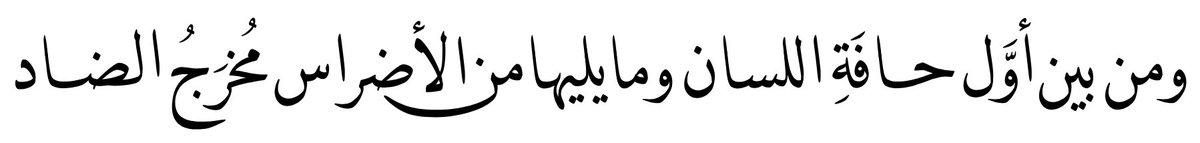

While many consonants share a maḫraǧ, the ḍād has a unique maḫraǧ described by Sībawayh as follows:

"And (that which is) from between the front of the edge of the tongue and what is on the side of it of the molars is the Muḫraǧ of the Ḍād"

The "molars" part is important here

"And (that which is) from between the front of the edge of the tongue and what is on the side of it of the molars is the Muḫraǧ of the Ḍād"

The "molars" part is important here

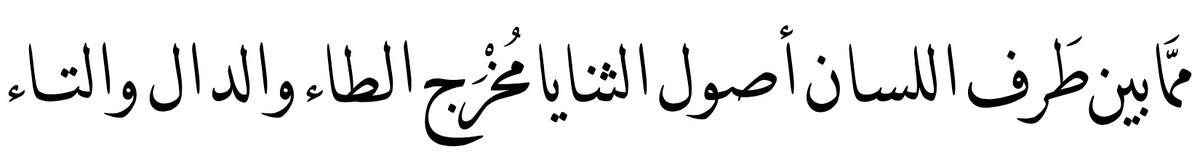

This is different from the description of the tāʾ, dāl and ṭāʾ which would share the place of articulation if the Modern Standard Arabic pronunciation was original: "From between the tip of the tongue and the base of the teeth is the muḫraǧ of the ṭāʾ, dāl and tāʾ."

The place of articulation 'along the molars' is an indication that it is a alveolar lateral consonant; one that is articulated in the same tongue placement as the "t" in English, but with a release along the sides of the tongue (along the molars) which is what "lateral" means.

Next Sībawayh tells us of two categories which somewhat align with 'airstream': Majhūrah and Mahmūsah.

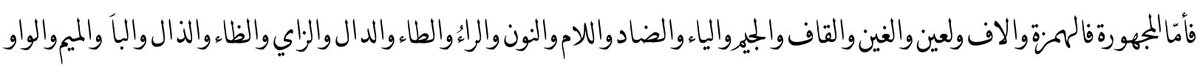

"And as for the Maǧhūrah (consonants) they are: ʾ, ā, ʿ, ġ, q, ǧ, y, ḍ, l, n, r, ṭ, d, z, ṭ, ḏ, b, m, w" (The rest are mahmūsah)

"And as for the Maǧhūrah (consonants) they are: ʾ, ā, ʿ, ġ, q, ǧ, y, ḍ, l, n, r, ṭ, d, z, ṭ, ḏ, b, m, w" (The rest are mahmūsah)

This categorization has perplexed scholars of Sībawayh, maǧhūrah mostly agrees with "voiced" (vibrating vocal cords). But that puts hamzah, qāf and ṭāʾ in the wrong category. People have tried all kinds of solution: Suggested that qāf (like modern bedouin dialects) was voiced.

And that maybe ṭāʾ was voiced too; or that Sībawayh simply made a mistake (sic!). But what is important here, no-one managed to explain the hamzah in this group, which is physiologically impossible to make voiced, as you use your vocal cords to articulate it.

Revolutionary work by Barry Heselwood and Janet Watson has now shown that Sībawayh was right all along, and that we were simply imposing the wrong (western) categories onto Arabic: Maǧhūrah is "non-turbulent airstream" which includes voices and voiceless unaspirated consonants.

And mahmūsah is "turbulent airstream" which creates a lot of "white noise" in recordings: Aspirated consonants and voiceless fricatives.

The qāf, ṭāʾ and hamzah were just pronounced as they are today, and Sībawayh did not make a mistake.

ḍād was voiced and non-turbulent.

The qāf, ṭāʾ and hamzah were just pronounced as they are today, and Sībawayh did not make a mistake.

ḍād was voiced and non-turbulent.

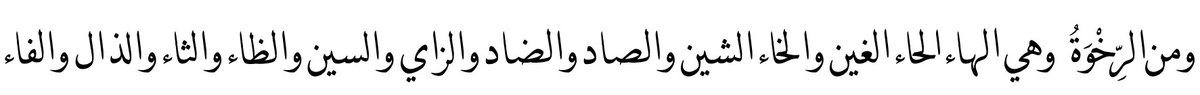

The next category talks about manner of articulation: Šadīd 'tight' versus Riḫwah 'slack' these categories align perfectly with "plosives" and "fricatives"

Šadīd: ʾ, q, k, ǧ, ṭ, t, d, b

Riḫwah: h, ḥ, ġ, ḫ, š, ṣ, ḍ, z, s, ẓ, ṯ, ḏ, f.

Šadīd: ʾ, q, k, ǧ, ṭ, t, d, b

Riḫwah: h, ḥ, ġ, ḫ, š, ṣ, ḍ, z, s, ẓ, ṯ, ḏ, f.

Note that the ḍād was a *fricative*; If it had had its modern pronunciation it would have been maǧhūrah (non-turbulent, like the dāl) but it would *not* have been a fricative (riḫwah), but rather a stop (šadīd).

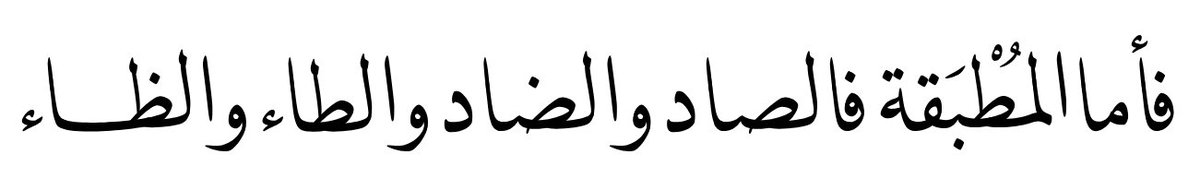

Finally, the ḍād is muṭbaqah 'covered with a lid'; referring to the backing of the tongue towards the pharynx or velum. "Emphatic" in Arabist parlance, "Pharyngealized" or "Velarized" in phonetics: "As for the Muṭbaqah, they are: ṣ, ḍ, ṭ and ẓ"

Let's bring it together: ḍād is:

+Pronounced from the edge of the tongue and along the molars (lateral)

+fricative (riḫwah)

+non-turbulent airflow (maǧhūrah)

+pharyngealized (muṭbaqah)

[ ɮˁ ] voiced pharyngealized apical alveolar lateral fricative

+Pronounced from the edge of the tongue and along the molars (lateral)

+fricative (riḫwah)

+non-turbulent airflow (maǧhūrah)

+pharyngealized (muṭbaqah)

[ ɮˁ ] voiced pharyngealized apical alveolar lateral fricative

The description of Sībawayh is very clear and unambiguous. But it is very rare to hear this sound produced along Sībawayh's description in modern Quranic recitation.

This is not some kind of difference between Quranic recitation and the Arabic Sībawayh describes.

This is not some kind of difference between Quranic recitation and the Arabic Sībawayh describes.

Ibn al-Jazarī in his "Našr al-Qirāʾāt al-ʿAšr" is quite explicit:

ḍād is unique. It should not be pronounced:

Like a ẓāʾ (common in many modern bedouin dialects).

Blended with the dāl (MSA pronunciation and common among reciters).

As an emphatic lām (some rare dialects do so).

ḍād is unique. It should not be pronounced:

Like a ẓāʾ (common in many modern bedouin dialects).

Blended with the dāl (MSA pronunciation and common among reciters).

As an emphatic lām (some rare dialects do so).

There are still dialects around that actually retain this ancient pronunciation of the ḍād, as described by Sībawayh.

jstor.org/stable/25702571

Do you know of any reciters that do not pronounce the ḍād as a dāl muṭbaqah, but in the way Sībawayh describes it? Let me know!

jstor.org/stable/25702571

Do you know of any reciters that do not pronounce the ḍād as a dāl muṭbaqah, but in the way Sībawayh describes it? Let me know!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh