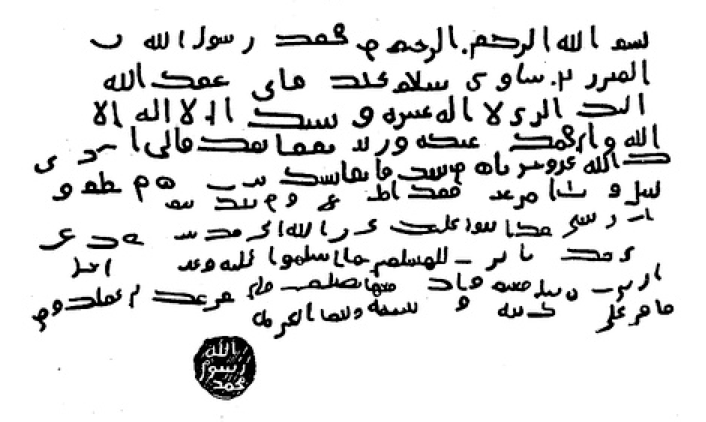

There are several letters of the prophet to several heads of state, which have been recorded in literary sources.

There are some documents out there, which are said to be the actual letters mentioned in these sources

Scholars rightly take these to be forgeries. Here's why:

There are some documents out there, which are said to be the actual letters mentioned in these sources

Scholars rightly take these to be forgeries. Here's why:

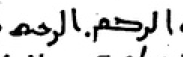

First, in some orthographic aspects, it is *much* too modern. All throughout the early Islamic papyri there was only one spelling of salām:

سلم، السلم

NEVER سلام، السلام.

1. Tracing of the Munḏir 'letter'

2. 65 AH papyrus.

3. ~60 AH papyrus

4. CPP (first century Quran)

سلم، السلم

NEVER سلام، السلام.

1. Tracing of the Munḏir 'letter'

2. 65 AH papyrus.

3. ~60 AH papyrus

4. CPP (first century Quran)

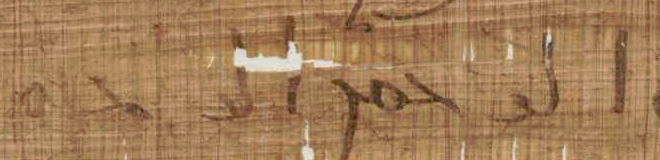

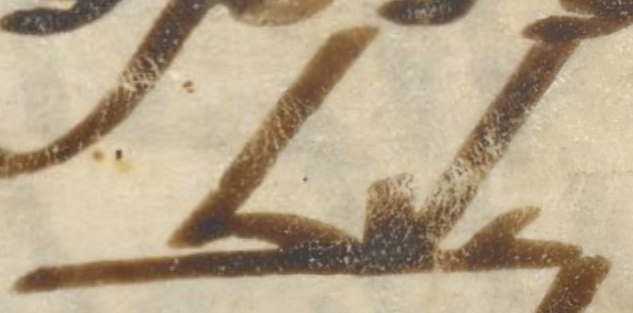

The shape of the rāʾ is wrong. In the early first century this is consistently a small semi-circle that ascends above and descends below the baseline. In these forgeries it has the modern shape.

1. Tracing of the Munḏir letter

2. PERF 558 (22 AH)

3. 60s AH papyrus

4. CPP

1. Tracing of the Munḏir letter

2. PERF 558 (22 AH)

3. 60s AH papyrus

4. CPP

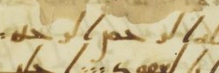

The final dāl is too 'Kufic'. Early manuscripts have much less broad dāls. The 'uptick' is also missing.

1. The munḏir letter.

2. 22 AH hāḏā

3. 42 AH ḏakara

4. 1st c. Quran muḥammad

1. The munḏir letter.

2. 22 AH hāḏā

3. 42 AH ḏakara

4. 1st c. Quran muḥammad

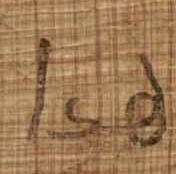

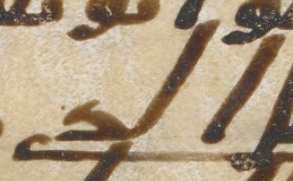

The forger seems to be unaware of the fact that word-final kāf is different from word final dāl and writes it in the same "hyperkufic" manner. It should have an upward stroke in final position.

1. Munḏir ʾilayka

2. 60s AH [fa-]ḏālika

3. 25-30 AH ʿalayka

4. 1st c. Quran ʿalayka

1. Munḏir ʾilayka

2. 60s AH [fa-]ḏālika

3. 25-30 AH ʿalayka

4. 1st c. Quran ʿalayka

And this one is funny: We would be required to assume the prophet spoke Fuṣḥā with a Turkish accent. He writes al-munḏir as المنزر!

He slips up again for allaḏī which he writes as الزى Oops! This can probably give us an idea where the forger was from.

He slips up again for allaḏī which he writes as الزى Oops! This can probably give us an idea where the forger was from.

A final reason to be skeptical about these forgeries is that they are *verbatim* the letters as we find in the literary sources. It is unlikely that the literary sources retained the letters (if they existed, and they may have) reproduced them down to the last letter.

So from this it should be clear that we *do not* have letters from the prophet. These are clearly modern forgeries. This does not mean that the letters mentioned in the literary sources are fake: They may have existed, but we only have those sources as proof of them.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh