Thread

"Systematic investing is more profitable and requires less time and effort [than discretionary trading]. A system removes emotion and makes it easier to commit to a consistent strategy." (p. vii)

amazon.com/Systematic-Tra…

"Indeed, professional gamblers usually have a better understanding of risk management than many people work in the investment industry." (p. ix)

"People have been using systems to trade for decades, but they are still in a small minority." (p. 3)

"But if everything is clearly defined, it creates a line in the sand beyond which any deviation is obvious." (p. 18)

"A system which is fully automated but not completely trusted is potentially lethal.

"I prefer systems that are objective, simple, transparent, & based on underlying hypotheses." (p. 19)

"In practice, experts fiddle with optimizations until the results reflect their own expectations." (p. 20)

"The size of your positions must reflect the amount of risk you can handle." (p. 23)

"Although the availability of derivatives has increased substantially, they are still a tool for the brave minority. Many institutional funds do not borrow either...

"As a result, undiversified portfolios are common, with equities contributing nearly all the volatility." (p. 35)

"As long as the position size of those forced to trade is greater than those who exploit them, opportunities will persist." (p.36)

"Two classic examples are the meltdown of LTCM in 1998 and the Quant Quake in 2007." (p. 45)

"There are two apparently easy ways to increase Sharpe ratios, both of which are incredibly dangerous.

"For example, the SR of Long-Term Capital Management, the fund which blew up in 1998, was around 4.6." (p. 47)

"However, this assumes that opportunities can be found at shorter time scales and ignores trading costs.

"It's impossible, even in theory, to trade expensive instruments quickly & profitably." (p. 47)

"Pooling your data is an excellent way of getting more data history...

"I have two rules which, for a single instrument, have Sharpe ratios averaging 0.05 and 0.30. Despite being perfectly uncorrelated, I'd need 45 years to distinguish them.

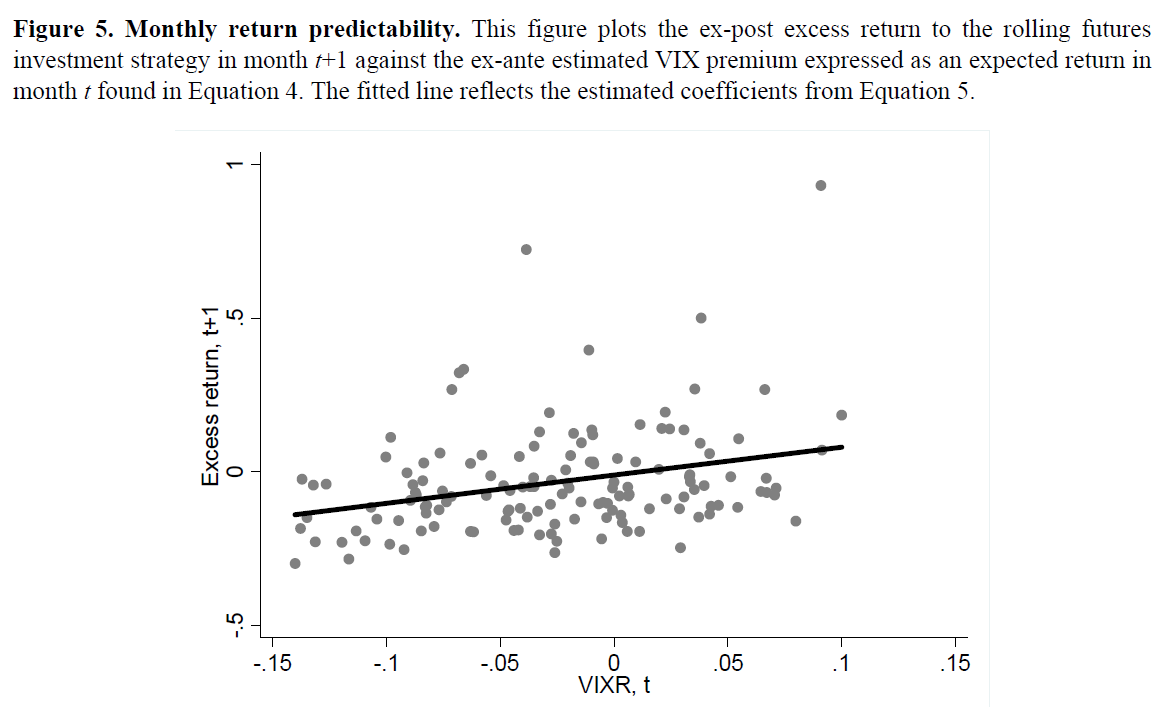

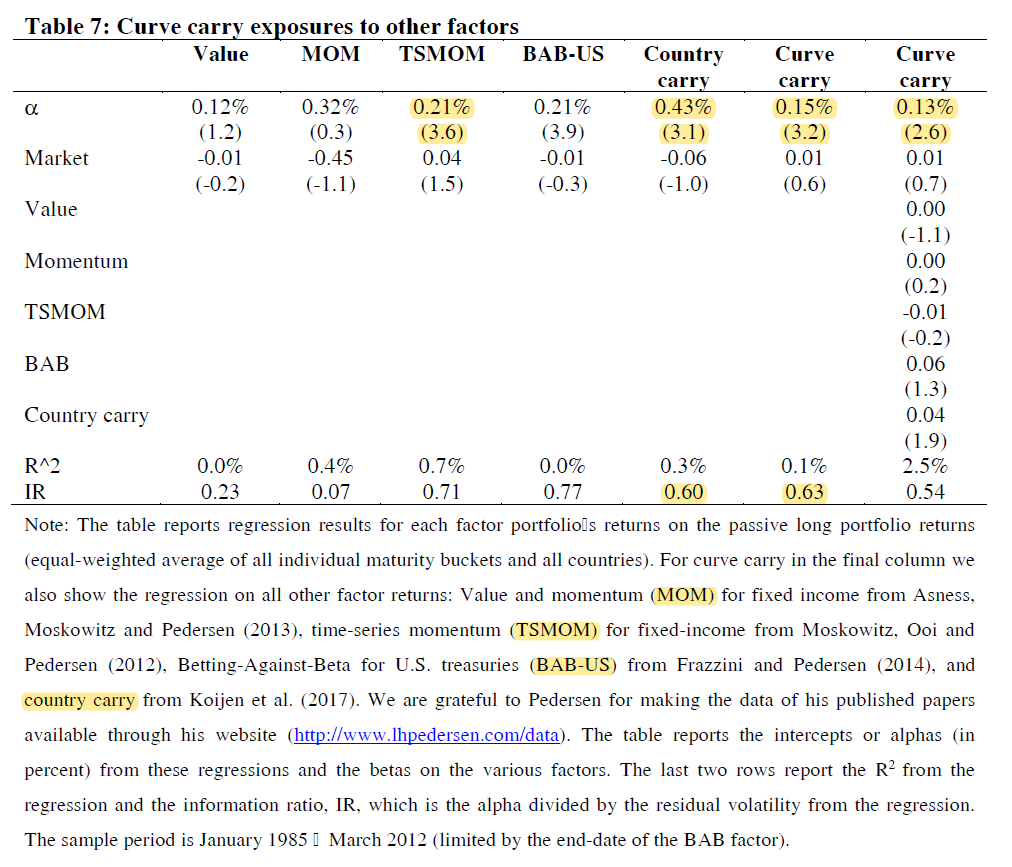

This is a theme AQR examines in detail for value and momentum:

A reasonable answer is to use them all:

The extra diversification can lead to lower risk and more reliable performance:

They find that market timing benefit is greater for shorter lookback windows, while longer windows get their performance from passive asset class exposure.

"Adding new instruments is a tiresome task of uploading and checking data, which is less fun than coming up with more trading rules, but it is of far greater benefit." (p. 68)

"The unspoken assumption is that the equation MUST be right." (p. 70)

"These effects are often not strong or common enough to exploit directly, but they should give you concern about betting too much when you have very strong forecasts." (p. 114)

"For many instruments, fast rules will be expensive to trade." (p. 122)

"The magnitude of the fall in σ depends on the degree of diversification." (p. 128)

"If the two assets are completely uncorrelated, the multiplier is 1.44.

"Correlations can be estimated with data from backtests or by using rule-of-thumb values." (p. 129)

Me: What do you mean by risk?

Advisor: Er... how would you define your tolerance for losing money?

Me: It could be how much I'm prepared to lose next year. Or tomorrow. Or next week. Are you talking about the absolute...

Advisor: Hold on. I need to speak to my supervisor..."

Carver: "I use an expected standard deviation as a volatility target." (p. 137)

"You'll also face unpredictable risks if your forecast of volatility or correlations is wrong.

"The volatility target isn't the maximum or even the average you might expect to lose in a year.

"2. In the event of losses, you'd probably reduce your positions if you're using trend following rules.

"3. You should reduce your positions when price volatility rises.

"Very low volatility instruments requiring insanely high leverage should be excluded." (p. 143)

"If you get your estimate of Sharpe ratio wrong and bet more than optimal, you have a large chance of losing your shirt." (p. 145)

"The absolute max. Sharpe we should expect is 1.0, regardless of how good the backtest is." (p. 146)

"It's far better to use half-Kelly.

"At the time of writing, I'm using a 25% target, reflecting my relatively low appetite for risk.

"Many negative skew strategies have fantastic back-tested Sharpe ratios, but I advise you to run them at half the risk you'd use for a more benign trading system." (p. 146)

"Use longer look-backs for instruments that are expensive to trade." (p. 156)

"Recent price volatility is generally a good way to get the right risk-adjusted position size....

"My research shows that this position inertia usually has a negligible effect on pre-cost performance, so there is no downside." (p. 174)

"Set a speed limit: a maximum expected turnover you will allow your systems to have." (p. 187)

"If you're realistic, the Sharpe ratio for each instrument using its own trading subsystem is unlikely to be higher than 0.40 on average." (p. 187)

"Assume the same pre-cost Sharpe but account for differing trading costs to adjust forecasted Sharpe ratios." (p. 194)

"You should do your own bootstrapping with realistic costs to check." (p. 194)

"More expensive-to-trade instruments usually perform better even once costs are taken into account, but only if they're traded relatively slowly (turnover <15 round trips/year).

"Unless bootstrapping tells you differently, assume the same pre-cost Sharpe ratio." (p. 198)

Thread with links to related research:

More is generally better:

"Be skeptical. Don't trust anybody.

"Be thoughtful. Understand your markets and your trading rules.

"You can't entirely eliminate risk, but you should quantify it and make sure you can cope with the likely downside." (p. 259)