Why (and how) is umami so delicious?

The answers relate to why we taste food at all.

Since so many of us are home-cooking right now, let's explore.

#medtwitter #tweetorial #moleculargastronomy

In 1907, a Japanese chemist named Kikunae Ikeda observed one night that a bowl of dashi broth filled with kombu (kelp) was particularly delicious.

He called this flavor "umami" and eventually isolated L-glutamate as its source.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27387211

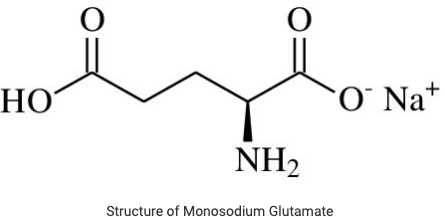

By 1909 Ikeda had extracted crystals producing pure umami flavor. He called these crystals Ajinomoto or "the origin of flavor" in Japanese.

We now know this compound by its chemical name, monosodium glutamate, or the ubiquitous seasoning MSG.

sciencehistory.org/distillations/…

For decades the existence of umami was disputed.

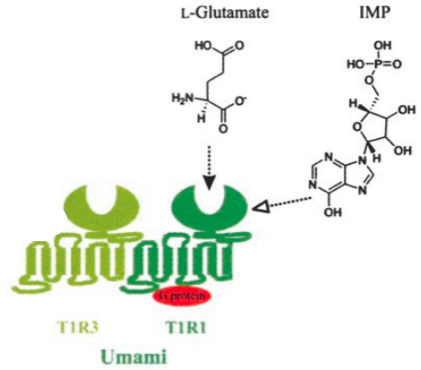

But in 2003 researchers knocked out a glutamate receptor complex (known as T1R1+3) in mice, eliminating response to MSG.

Humans have T1R1+3 on our tongues too. The mechanism of umami had been found.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14636554

About 2% of the population cannot taste umami.

These individuals have polymorphisms in the T1R1+3 receptor that blunts their response to glutamate, confirming that T1R1+3 actually represents the umami receptor in humans.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21422378

Other molecules also signal through T1R1+3, including inosine monophosphate (IMP, a purine nucleotide).

Some umami-rich foods only contain glutamate (eg tomatoes, cheese) while others have glutamate and IMP (eg bonito, beef).

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15353592

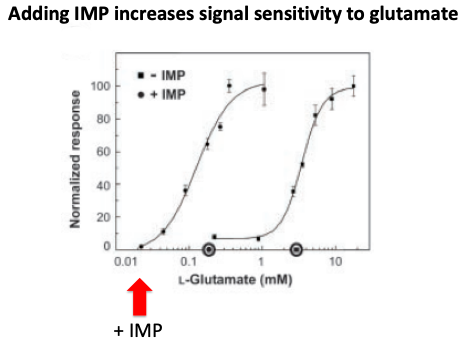

When glutamate and IMP are combined, the signal strength through the T1R1+3 receptor synergistically increases 30-fold (probably because of conformational receptor changes).

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11917125

This synergistic signaling explains how cooking with different umami sources like soy sauce and shitake mushrooms (glutamate) with chicken or beef (IMP) leads to such intense umami flavor (the so-called "umami bomb").

epicurious.com/expert-advice/…

Now, why is umami so delicious? Does it serve a purpose beyond flavor?

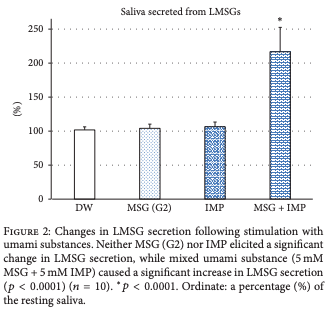

Umami does increase saliva production more than other types of taste (with a similar synergy when glutamate and IMP are combined).

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P…

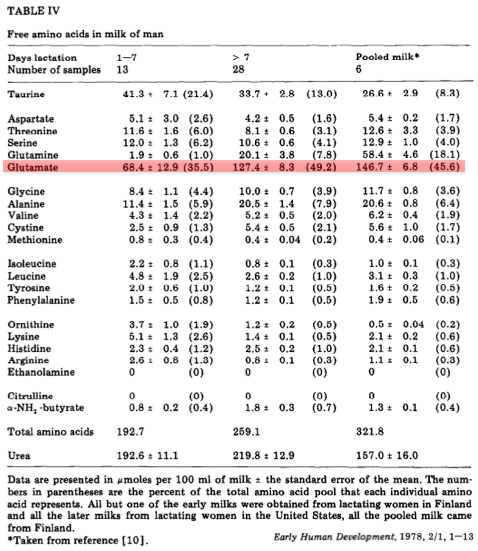

And glutamate is the most common amino acid in breastmilk.

▶️ Umami is so fundamental, it's the first taste that babies experience.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/102507

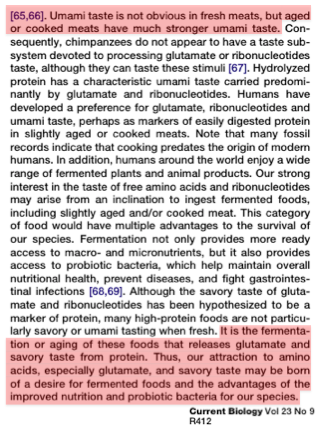

Umami also cues our brains that food contains protein, but it may serve an even more specific purpose.

When our early humans began cooking/fermenting, it gave them access to increased dietary micro/macronutrients and probiotic bacteria.

This was a major survival advantage.

Hydrolysis from cooking/fermenting breaks down protein and nucleotides, releasing glutamate and IMP and ⬆️ umami flavor.

Umami, therefore, incentivized our ancestors (and us) to eat cooked/fermented food.

We've reaped the benefits ever since.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23660364

One final note.

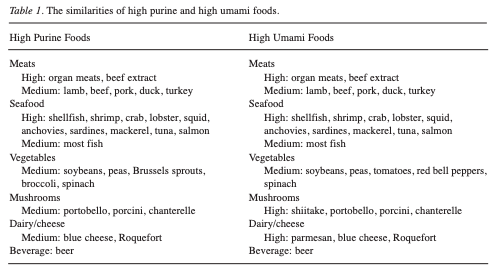

We generally recommend that patients with gout follow a low purine diet.

Not surprisingly, purine-rich foods are full of umami, which may explain why that diet is hard to adhere to.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24187156

✅ Umami results from glutamate/nucleotide signaling via the T1R1+3 receptor complex

✅ Combining umami inputs synergistically ⬆️ T1R1+3 signal strength, heightening flavor intensity

✅ Umami may have had a survival advantage for early humans who began to cook/ferment food