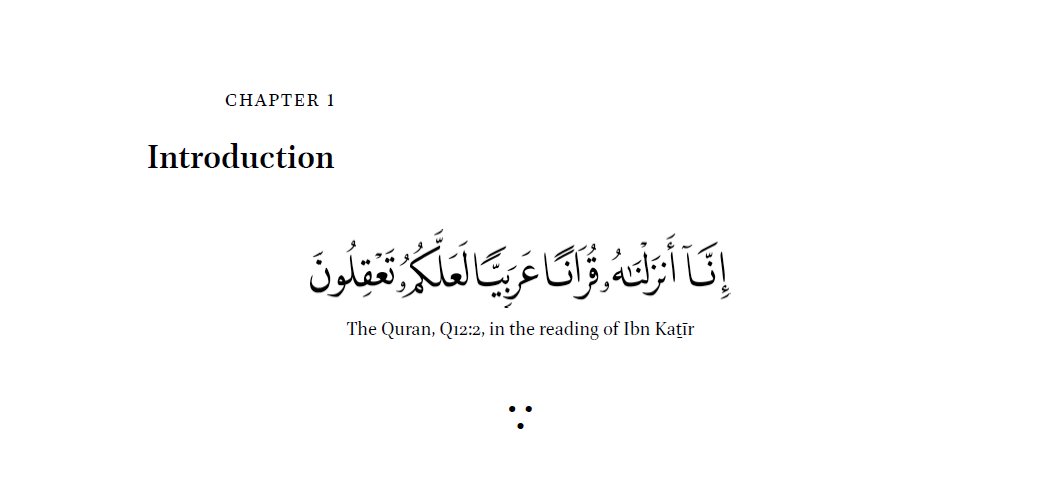

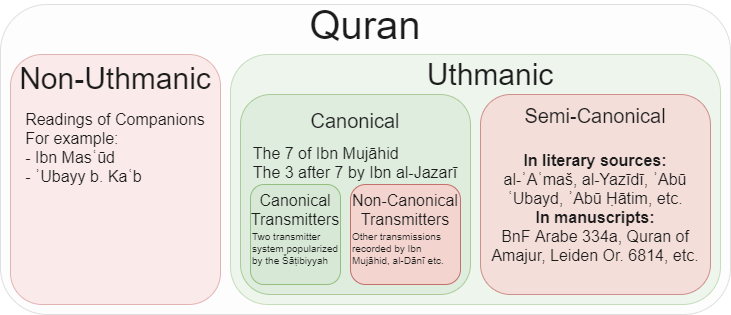

Here's a very nice infographic on the development of the canonization of the Quran by @NaqadStudies. In the comments an interesting discussion developed on what "Semi-canonical Qurans" means and how they related to the reading traditions. Here's a small thread.

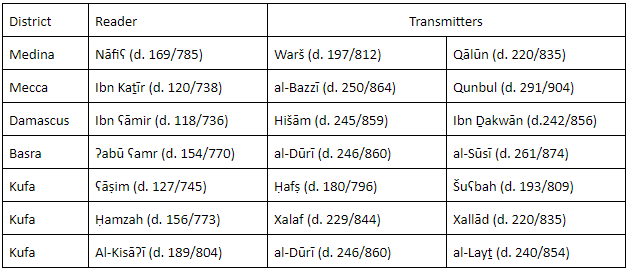

Today there are 10 Quranic reading traditions which are all considered equally valid and canonical. The first seven of these were canonized by Ibn Mujāhid who died in 324 AH. Centuries later Ibn al-Jazarī (d. 751 AH) manages to get three more accepted into the canon.

Each reading tradition is associated with an eponymous reader, a learned person whose reading became so popular that reciting in that style became equivalent to reading the Quran in their name. These eponymous readers were mostly active in the 2nd to mid-3rd c. AH.

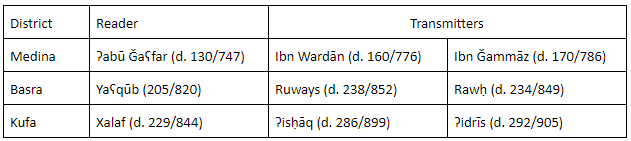

People who transmit readings in the name of these eponymous readers are called transmitters of these readings. Often they are direct students, but sometimes they are one or two generations removed. Ibn Mujāhid collected many different transmission paths from the readers.

Some time after Ibn Mujāhid's lifetime, a consensus develops to consider only transmitters of each eponymous reader canonical, this leads to the "two transmitter canon" as we know it today. Ibn al-Jazarī followed this model and has two transmitters for the 3 after the 7 too.

These readings differ from one another in more, and less significant ways. Sometimes they read words slightly differently, leading to differences in meaning of the text. By far the most common difference are of phonology (sounds of the language) and morphology (shapes of words).

But what about the period before Ibn Mujāhid's canonization? Were there other readers? Certainly! The literary tradition records many other characters with their own reading: al-ʾAʿmaš, al-Yazīdī, al-Ḥasan al-Baṣrī, Ibn Muḥayṣin, ʿĀṣim al-Jahdarī, ʾAbū ʿUbayd etc.

Besides that, there are reports of earlier figured, often companions of the prophet who were also said to have had their own reading, most notably ʾUbayy and Ibn Masʿūd are fairly well-recorded. There is however a fairly important difference between these two types of readings:

During the reign of the third Caliph ʿUṯmān, he standardized the Quranic text, and the vast majority of the readers that were not companions of the prophet, stick to different interpretations of the standard text. They are non-canonical but, as I all it "Uthmanic".

The companions, however, developed their own readings before there was a standard text, and their reading can differ much more significantly in wording. Some later readers also sometimes deviate a little from the standard text (like Ḥasan and al-ʾAʿmaš), but this is negligible.

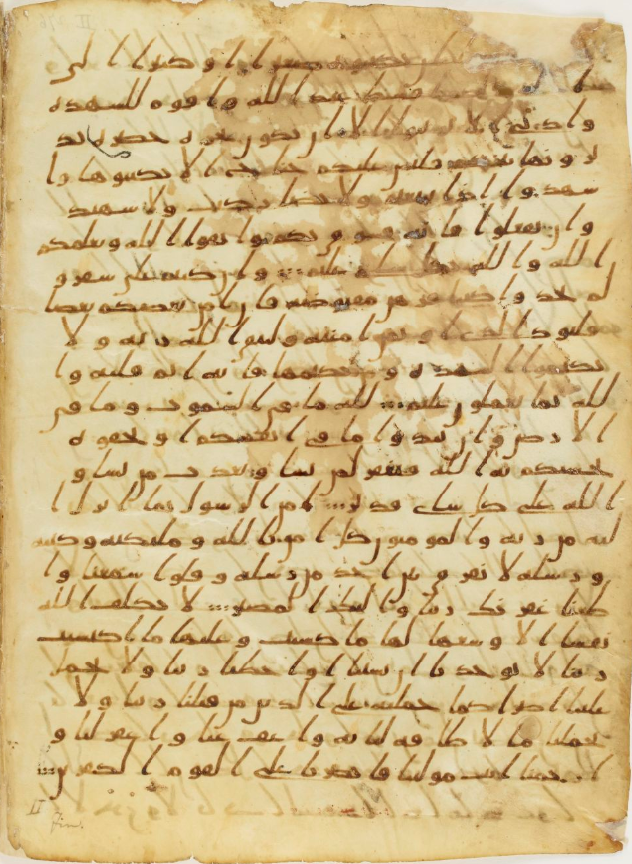

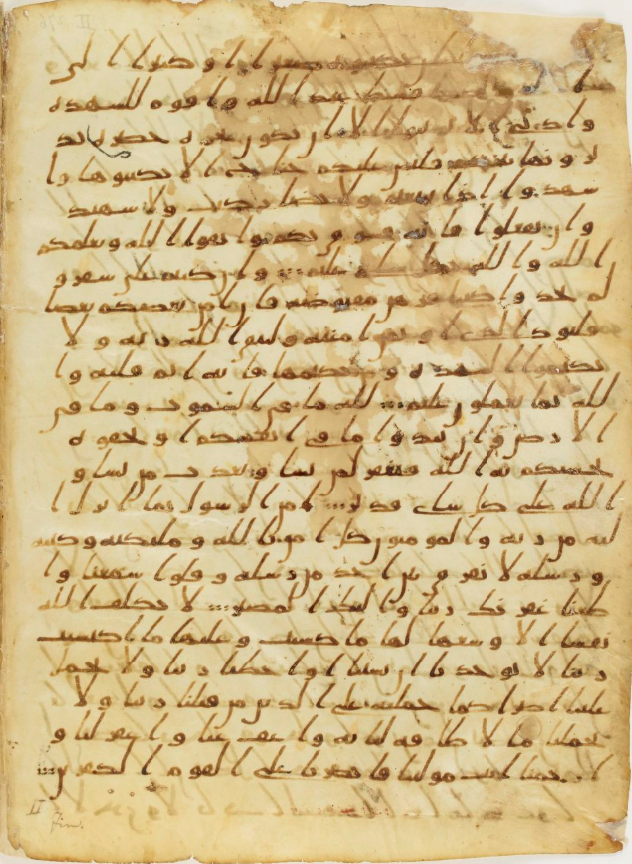

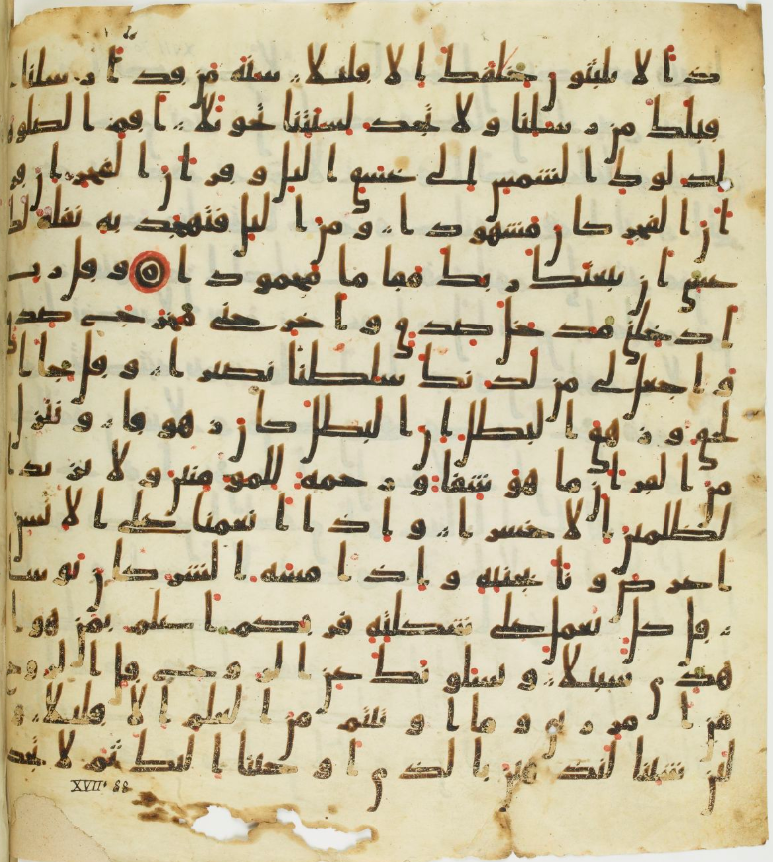

Now, onto manuscripts and the readings within them: all but one manuscript adhere to a single standard text, the Uthmanic text, but the very earliest manuscript lack vowel signs and many consonantal dots; The differences in readings come primarily from vowels and some dots...

As a result, these manuscripts do not really contain a "reading", there is only a consonantal skeleton upon which a variety of different readings can (and are!) imposed. So a Kufan manuscript can accomodate all the four canonical (and other non-caonical) Kufan readers.

This is also why it is very problematic to claim that such early manuscripts are written "in" a reading of so-and-so. It is also deeply anachronistic. Arabe 328 and Or. 2165 are both Syrian manuscripts that predate the Syrian reader's career by quite some time...

Therefore you cannot say that these manuscripts (which are definitely Syrian, based on some consonantal variants and verse divisions!) are written "in the reading of Ibn ʿĀmir". This is my main criticism with Yasin Dutton's work on these manuscripts (which is otherwise brilliant)

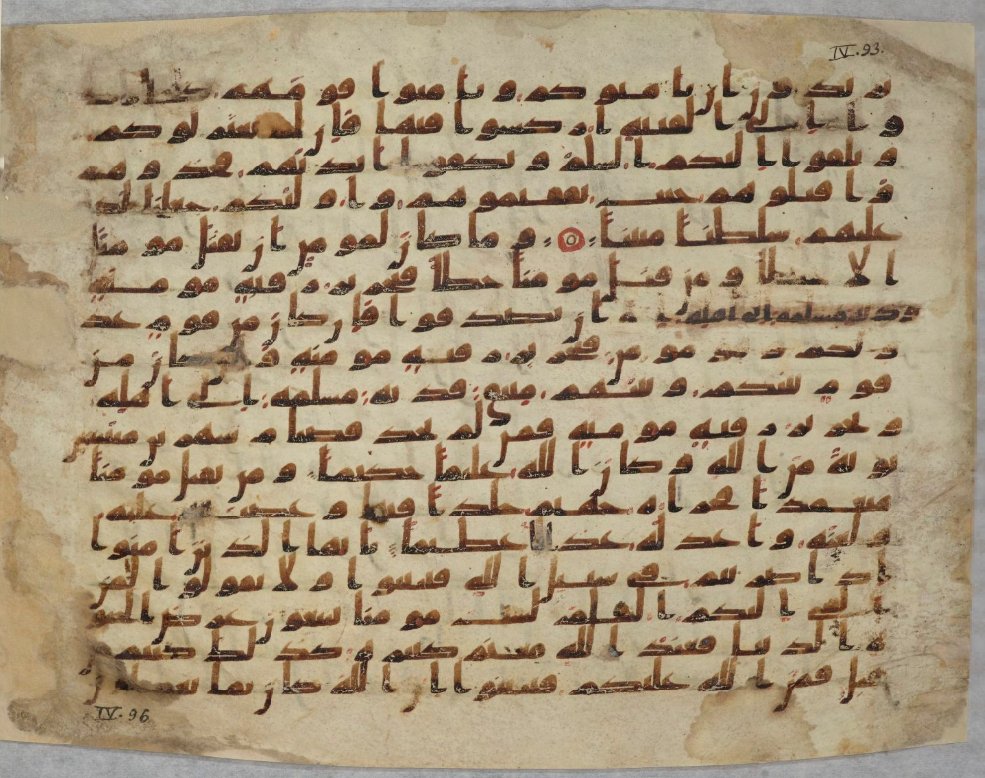

Once vowel signs are added, we can say manuscripts contain readings. Some are written in identifiable readings. @barisincekurdi showed in his BA thesis that Arabe 330b is perfectly written according to Ḥamzah (red dots) and Nāfiʿ's transmission Warš (green dots).

Others, such as Arabe 334a, however, follow a system which we do not recognize from the literary sources at all. These are similar to non-Quranic readings that they are all Uthmanic: they closely follow the standard text, it is just interpreted differently

academia.edu/41060428/Arabe…

academia.edu/41060428/Arabe…

This last group of manuscripts, along with readings recorded in the literary sources which don't make it into the canon of the 10 can be called as semi-canonical (they follow the Uthmanic text, but are not canonical). Transmitters of canonical readers can ALSO be non-canonical.

Altogether, you get a little something like this. These subgroups became canonical at different times. Uthmanic: ~650, Readers ~1000, Transmitters ~1400 CE

If you like content like this, I now have a Patreon, please consider throwing me a couple of bucks!

patreon.com/PhDniX

If you like content like this, I now have a Patreon, please consider throwing me a couple of bucks!

patreon.com/PhDniX

It's terrifying to start this Patreon thing... but my academic future has never looked so uncertain, and doing threads like these, which I love doing, do take time and effort.

If you'd consider becoming a patron let me know what you'd like to see as tiers and exclusive perks!

If you'd consider becoming a patron let me know what you'd like to see as tiers and exclusive perks!

I somehow managed to fail to link to the infographic! Oops. Don't know what happened there.

https://twitter.com/NaqadStudies/status/1265265807686340608

ADDENDUM: just noticed that my link to the infographic somehow didn't work. here it is!

https://twitter.com/NaqadStudies/status/1265265807686340608

ADDENDUM: If you would like to support me, but don't feel like committing to a monthly donation, you can also consider throwing me a couple of bucks as a one off thing through Ko-Fi! ko-fi.com/phdnix

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh