sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

In short, we all THINK we know what question we want answered, but do we? And are we willing to do the research we need to do, to get that answer reliably?

table for all kinds of reasons.

What will the patient want?

Angiogram shows a tight lesion?

What will the patient want?

Likewise advice to stop smoking is equally VALID from a smoker as for a non-smoker.

I would argue that as interventional cardiologists trained in a previous era, it is too late for us.

Max Planck, Scientific autobiography, 1950, p. 33, 97

Science progresses

one funeral

at a time

Planck's Principle

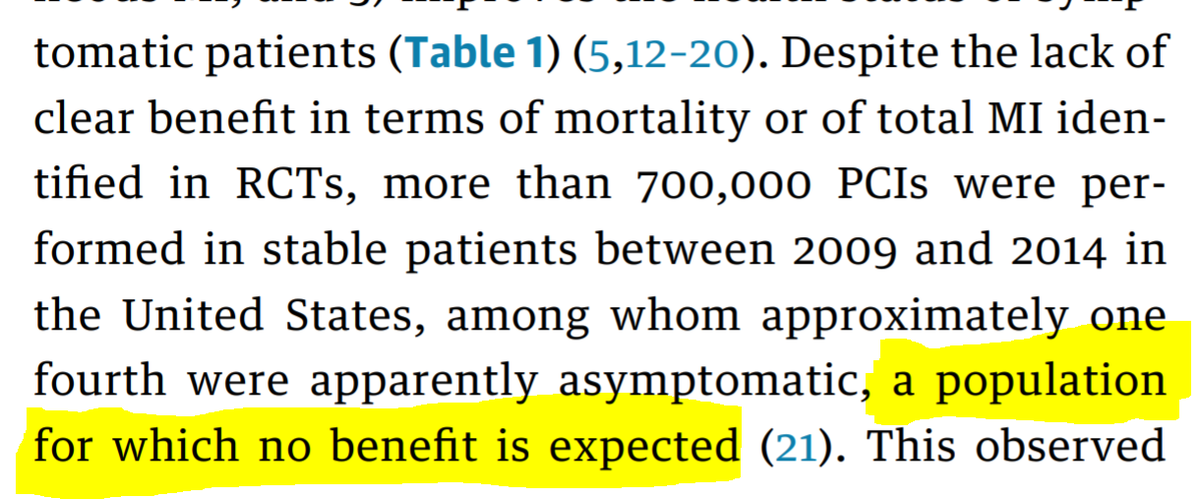

We have long thought that research to *test* it is merely an academic obsession of no practical merit.

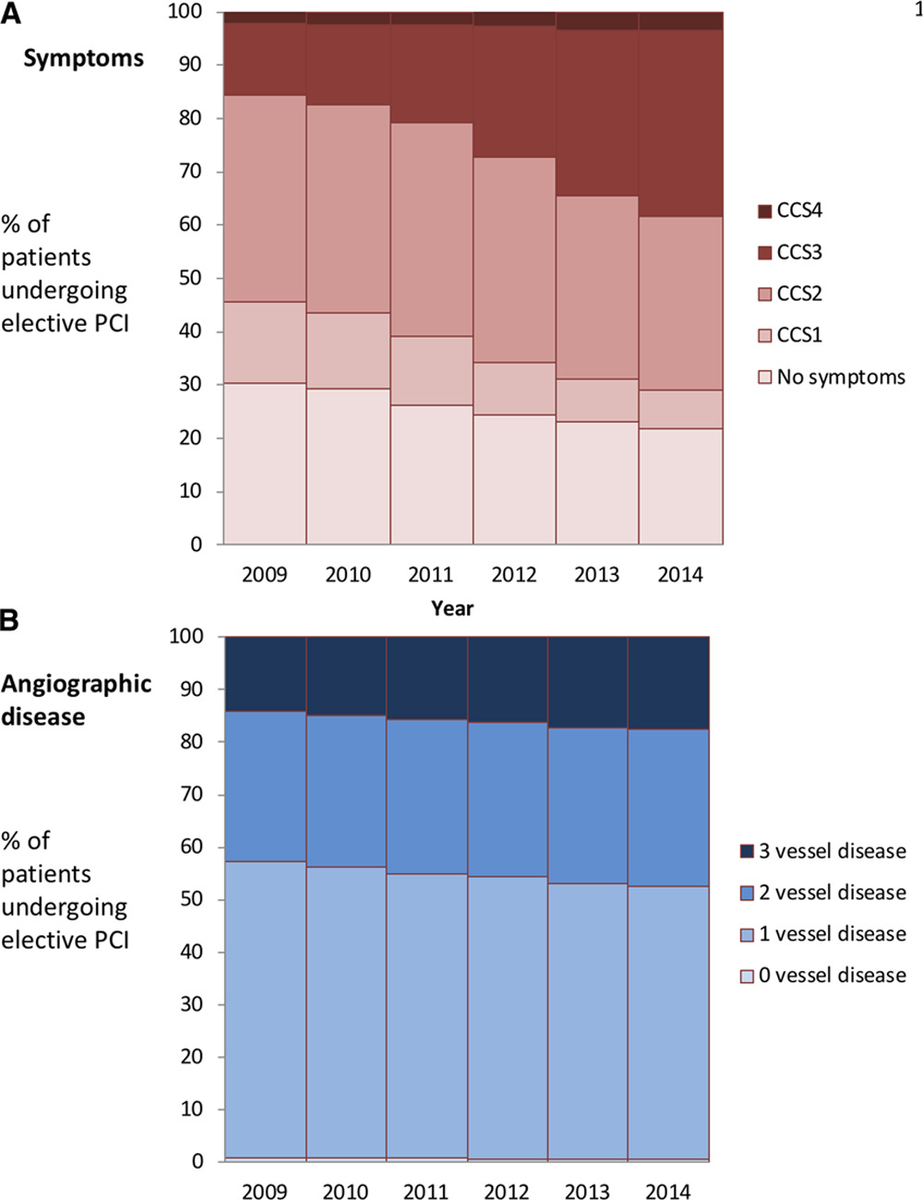

USA figures from NCDR:

ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CI…

S Burns and D Francis

Annals of Excuses for KoLs, 2020

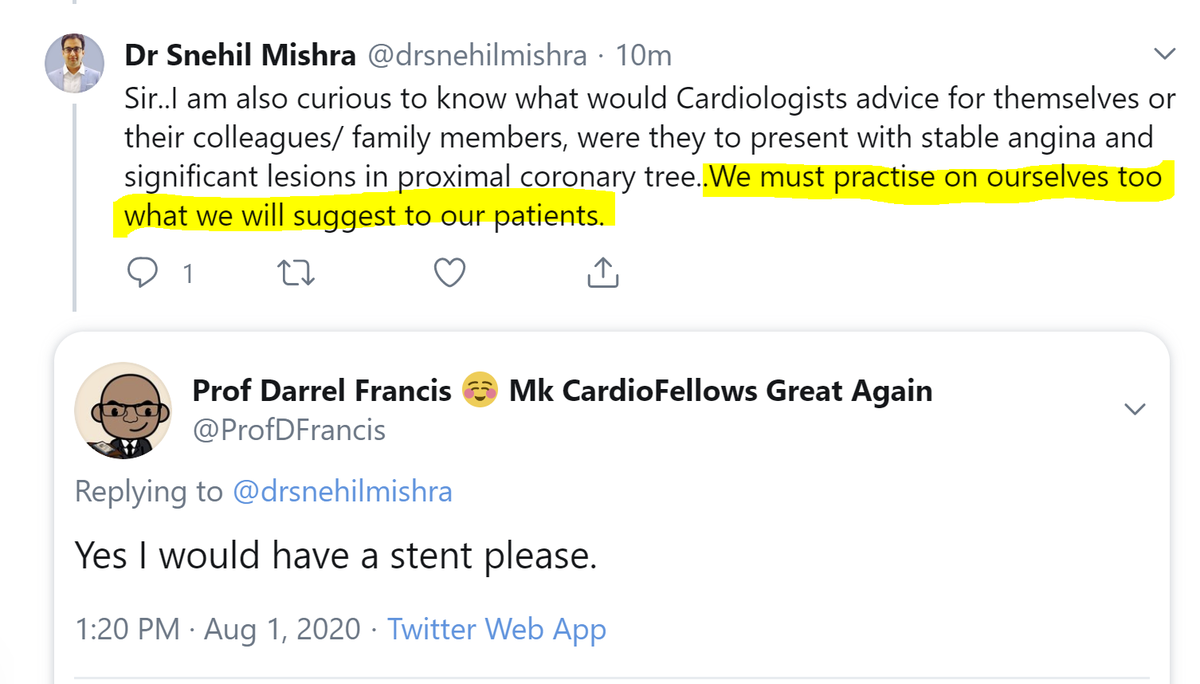

So to put us in the right frame of mind, let's ask ourselves this. (Vascular surgeons please do not answer.)

Suppose you develop leg-gina. What would you want to have first?

And how about elbo-gina? Pain when you throw darts in a pub.

Unless it happens to be an-gina, at which point we blow our top and start scurrying about like terrified rabbits.

We know a stent is simple and safe.

EVERYONE we know professionally thinks the same as us.

So even our "lay network" pushes us to PCI.

Some people can't do that. But that would be like a drug addict being unwilling to warn off children from taking up the bad habit.

What they did after they completed the trial and exited, which is in most cases have PCI if not received during the trial, is exactly what we were expecting and recommending.

This will instantly make him understand that he should be more precise.

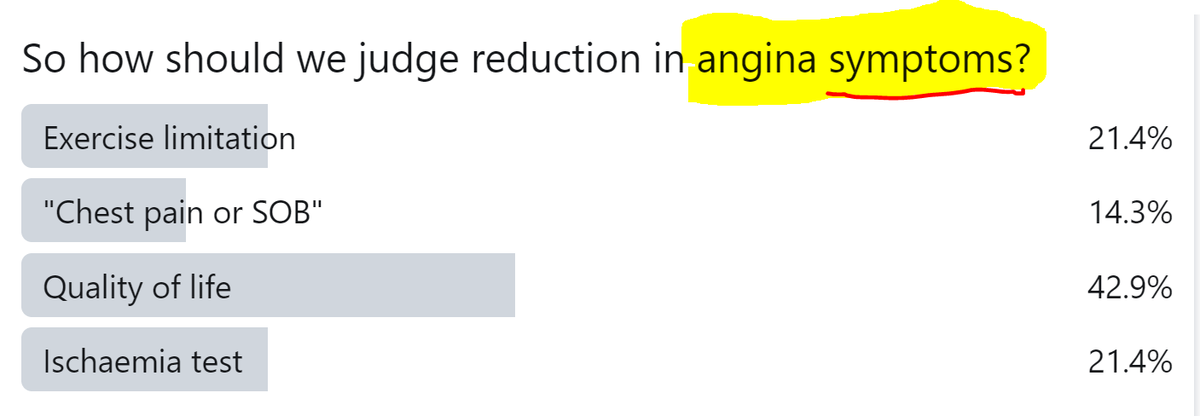

(1) Does the endpoint matter to patients?

(2) Is its evaluation unbiased?

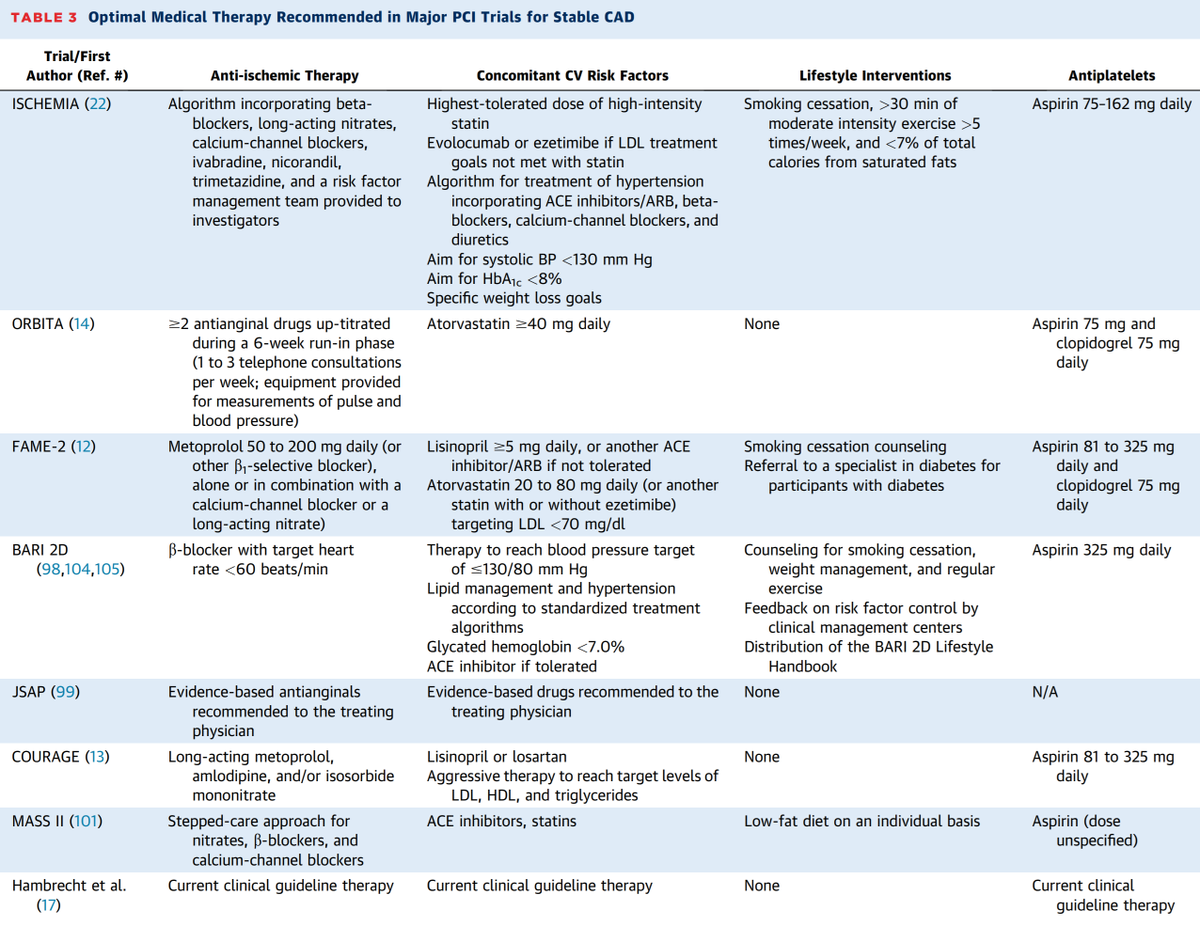

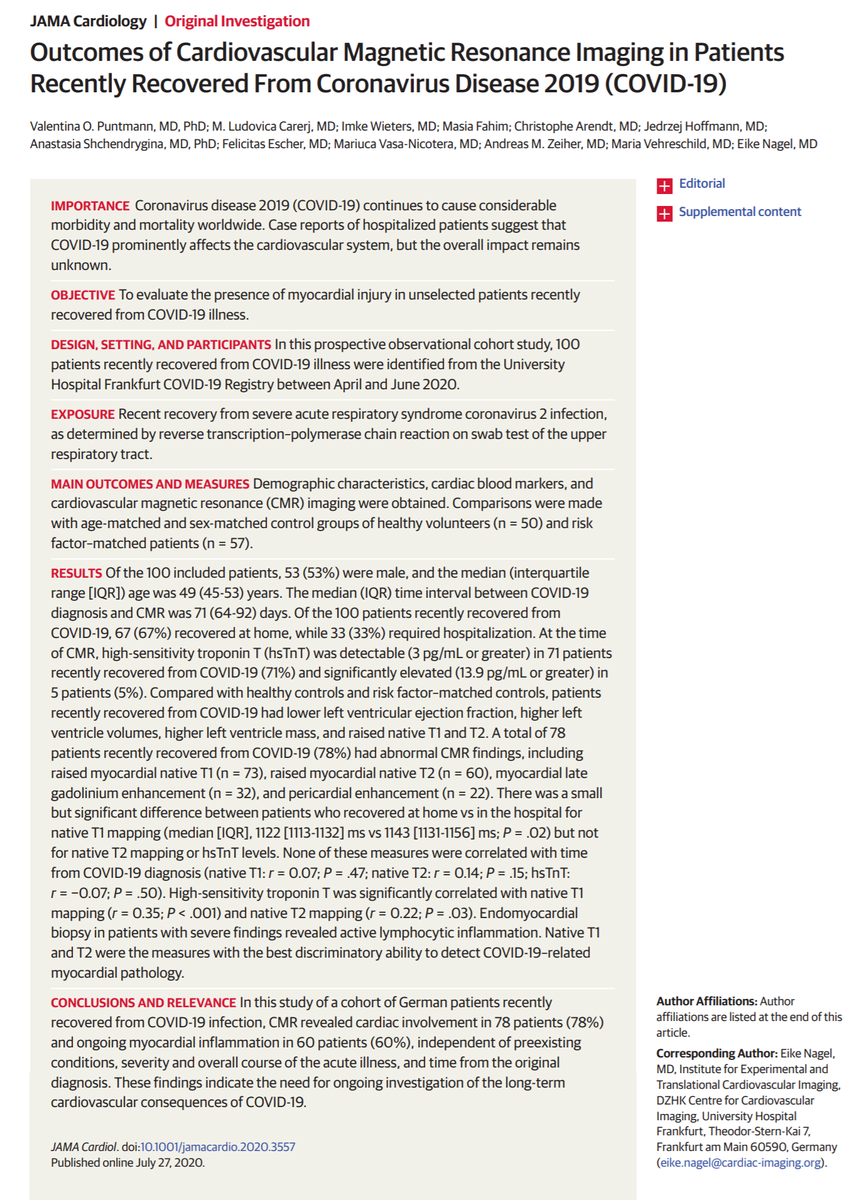

The classic proof of this is from DEFER and FAME 2.

Some MI's are disruptive to the patient's life, making them go in to hospital. Others are not, in the sense that we pick them up incidentally, such as discovering raised troponin after elective PCI.

i.e. Is an option that prevents one of one category and adds one of the other category, perfectly neutral?

i.e.

"let's make a big distinction between the MI's that bring you into hospital, and those that are documented incidentally"

But I already know which way this tilts the scales.

But again, we know in advance which way this tilts the scales.

It needs a choice. How to prevent bias?

The idea is to prevent bias.

However, how does that help when we are CHOOSING the endpoint DURING DESIGN of the trial, when we know the effect of our choice?

Because we see nice-sounding things like "blinded" and "pre-specify" and we assume they fix everything.

But they don't, and we don't think enough about it.

"If we only measure reduction in CHEST PAIN, we will underestimate the benefit of PCI on symptoms."

An exercise test nicely captures the limitation, regardless of whether it is experienced as chest pain or as shortness of breath.

HOWEVER, it also captures the limitation if it is non-cardiac.

HOWEVER, what is the difference between that an somebody who is a bit chubby and has asymptomatic ischaemia?

But there are many influences on it, of which angina symptoms may be a small minority. So even a useful effect on angina (whatever that may be) may be drowned out by irrelevant noise.

Anatomy (1)

Physiology (2)

Ischaemia imaging (3)

from "Definite angina" when we knew they had a full house of anatomy, invasive physiology and ischaemia imaging,

to "Atypical twinges" when we know they had a full house of all-clear's.

And the patients report symptoms daily.