For you lovely energy and climate folks who don't think about coal all the time: what's going on in the Powder River Basin

(the coal region mined in Wyoming that produces ~40% of US coal from ~10-15 enormous mines)

is a *REMARKABLY* big deal.

(the coal region mined in Wyoming that produces ~40% of US coal from ~10-15 enormous mines)

is a *REMARKABLY* big deal.

https://twitter.com/taykuy/status/1313123245076475904

I'm fairly comfortable saying that if you are going to mine coal (with the CO2 implications and all), the PRB is one of, if not the best, place in the world to do it.

The coal is pretty clean other than carbon (we mine there ~bc of the Clean Air Act), remediation is relatively easy (very thick shallow seams in flat, dryish land), and bc mining started with the advent of the environmental movement, things proceeded with that regulatory context.

The mines are *huge.* Like, miles across. Like, there's a separate town basically for workers at the southern end, and workers use something that looks a lot like the Google buses from SF to Mountain View to travel the distance.

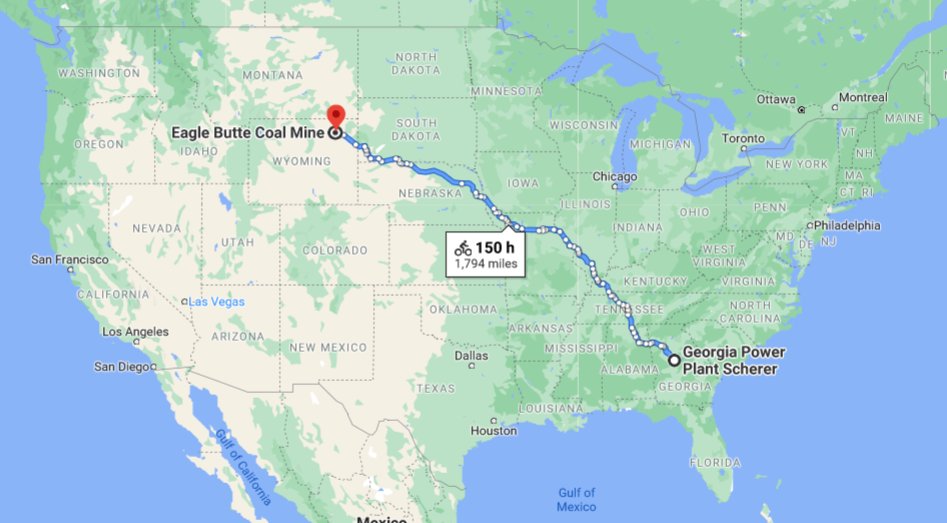

The mines are also deeply embedded in US coal use. In class the other day I satellite image field tripped my class between the giant coal plant south of us here in Georgia to some of its source mines, in the PRB.

(For laughs, and directness, bike directions:)

(For laughs, and directness, bike directions:)

So the fact that people are talking about closing some of these mines (partly due to a busted JV, partly due to winds of change, partly due to the fact that the current owners are pretty competent and see what's coming) is a *big* deal.

I was musing last week about how we square the circle of assuming the ngas system will be around to supply rarely-used turbines under deep decarbonization, and whether we'll see extraction retirements drive plant retirements.

I'm not up on the immediate buzz around the PRB but closing PRB mines is one of those things that might drive plant retirements. It works both ways, of course -- but you don't keep a 10-mile-across mine open to feed a couple plants.

Little known fact: not all coal plants can burn all coal, just like not all refineries can refine all oil. So although plants could shift to other PRB suppliers, they can't easily shift to non-PRB suppliers.

All of this is fascinating to me because coal really is (forgive this) the canary in the coal mine of decarbonization.

So far: we see environmental and labor liability discharge; no-notice layoffs; huge remediation burdens; and increasingly less competent operators taking over assets with big potential socioenvironmental impact.

The coal industry is tiny compared to the rest of the fossil industry. We need to be extraordinarily thoughtful about what we can learn from coal transition issues to date, to plan and better manage this transition.

Lots of lessons here for other industries -- coal *is* different, but it's not /that/ different.

Planning, announcements, glide paths, explicit naming of the places and facilities that need to close, etc. -- all these can help with a #JustTransition.

Planning, announcements, glide paths, explicit naming of the places and facilities that need to close, etc. -- all these can help with a #JustTransition.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh