Ok, this one is not going to make me a ton of friends on Climate Twitter but out of both curiosity, and in the name of scientific completeness, somebody had to perform these calculations.

journals.plos.org/plosone/articl…

journals.plos.org/plosone/articl…

Above is our new study that adds costs of climate change mitigation to recent high-profile estimates of the economic damages from climate change from Burke et al. (2015/2018).

nature.com/articles/s4158…

nature.com/articles/s4158…

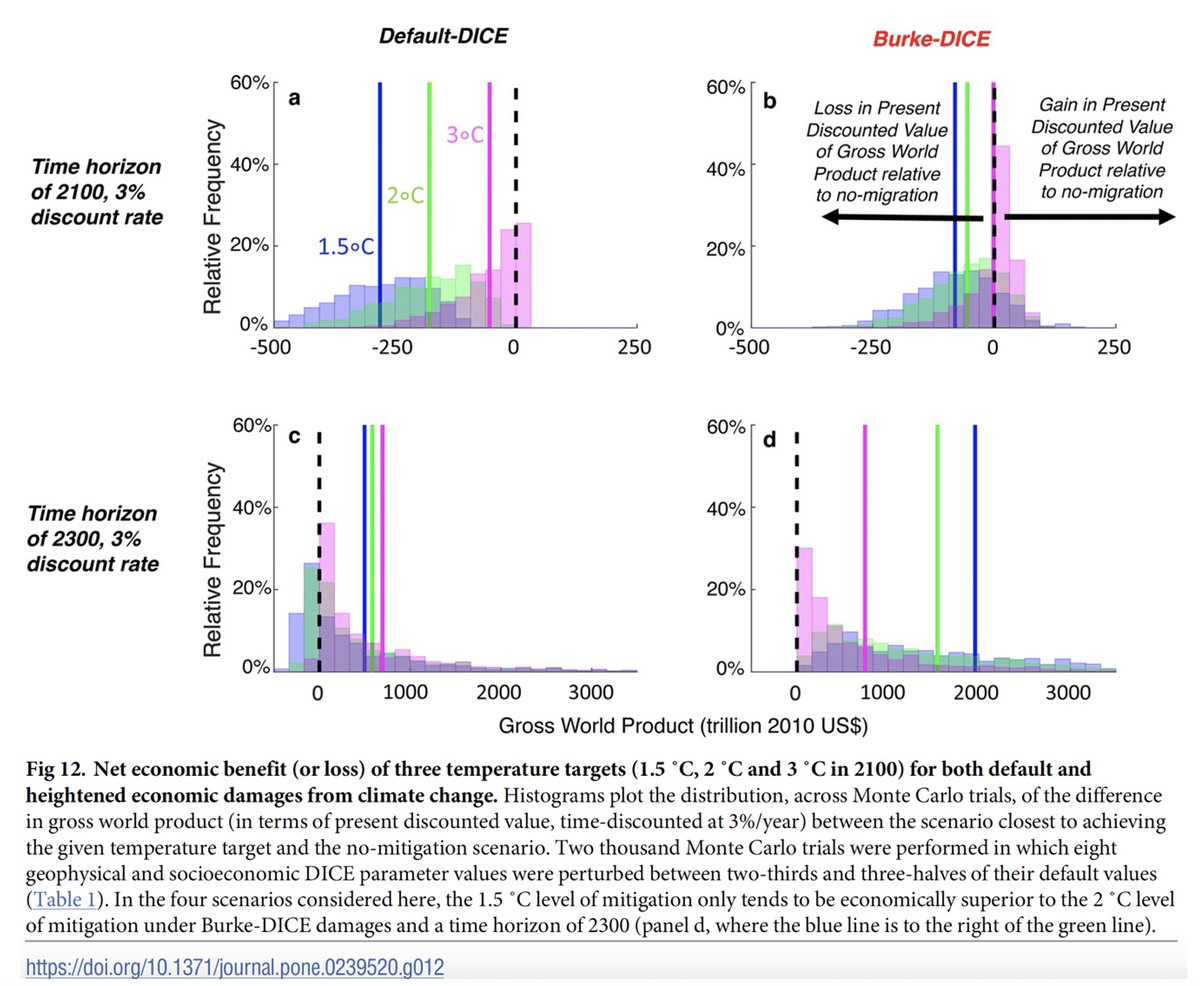

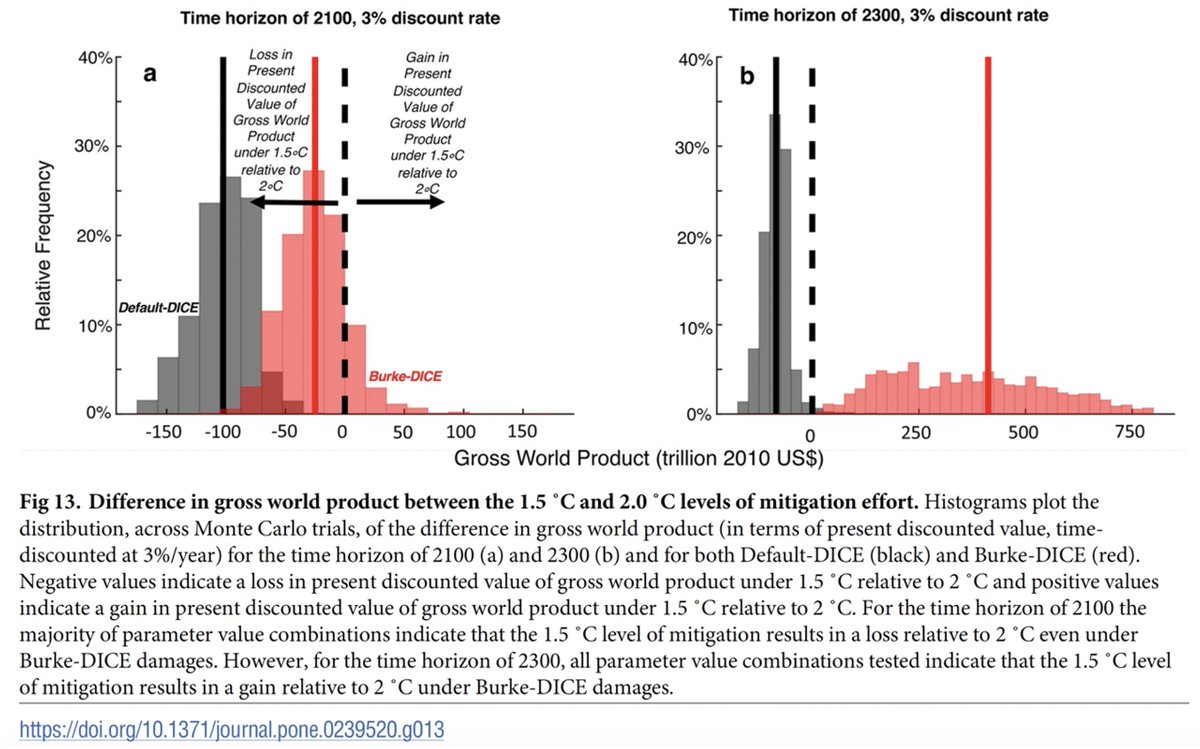

It shows evidence that the strictest Paris Agreement goals would not be net economically beneficial (in terms of global GDP) this century but that they would pay off in the 22nd century.

The Burke et al. (2018) study, “large potential reduction in economic damages under UN mitigation targets” was reported on with generous headlines like “Hitting toughest climate target will save world $30tn in damages, analysis shows”

theguardian.com/environment/20….

theguardian.com/environment/20….

However, that study amounted to a “benefit analysis” of Paris targets rather than a “cost-benefit analysis”. They also seem to dismiss the possibility that costs could be as large as the benefits they calculate.

Is it true that the costs of mitigation to achieve 1.5°C (relative to 2.0°C) are not nearly as large as the benefits of avoided damages through 2100? Based on available estimates of mitigation costs, probably not.

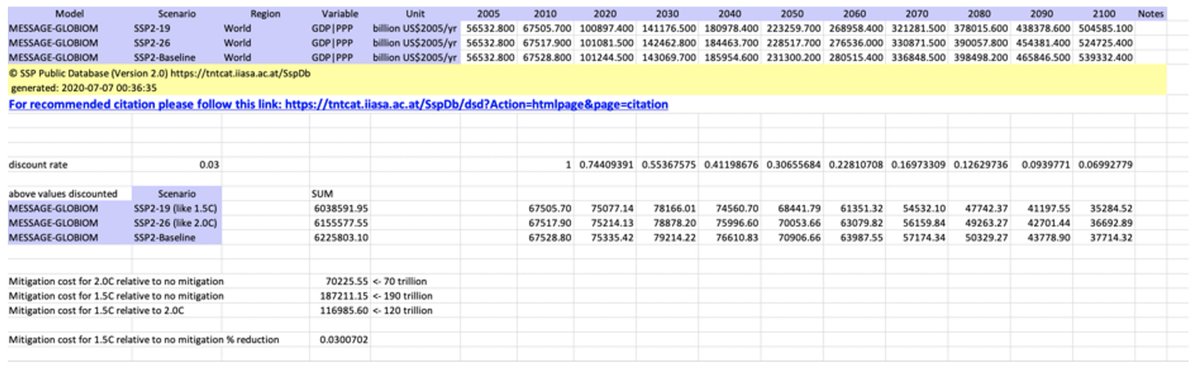

The IAMs used by the IPCC can provide estimates of mitigation costs. MESSAGE-GLOBIOM estimates that it costs $120 trillion more to stay below 1.5°C than 2.0°C, demonstrating that the additional costs required to stay below 1.5°C are larger than the additional avoided damages.

Our paper conducts a similar calculation to the back-of-envelope cost-benefit calculation above but in a more sophisticated and rigorous way.

We found that limiting global warming to 1.5°C results in a net loss of ~$40 trillion in global GDP relative to 2°C & that even the 2.0°C goal entails a net loss relative to business as usual through 2100. However, the sign reverses & these investments pay off in the 2100s.

So the economic gains are in the 22nd century. That is, of course, still motivation to meet these goals, but it illuminates why it is so difficult to get done, something we discussed in our recent break-even year paper:

iopscience.iop.org/article/10.108…

iopscience.iop.org/article/10.108…

Note on cost-benefit analysis in climate: When expressed in dollars, it may seem as though we are talking about trading off something superficial (money) against something of an intrinsically higher value (the Earth). But those $ costs really represent material human wellbeing.

Why? Because transitioning from energy-dense fossil fuels back to more dilute and intermittent renewable sources of energy like solar and wind requires more in terms of land, human time, and machinery to produce the same amount of energy.

This increase in resources required to produce energy has been advertised as a good thing since it creates jobs but that also means that there are fewer resources available to raise the standard of living of people in other ways.

patricktbrown.org/2018/08/15/fun…

patricktbrown.org/2018/08/15/fun…

Furthermore, it is the world’s least-fortunate that these costs might be disproportionally imposed on b/c one of the most "effective" ways to meet strict temperature targets would be by limiting the material well-being growth (& thus energy consumption) of the developing world.

See below for an example of the real-world, on-the-ground challenges associated with decarbonization in the developing world:

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

Limiting energy consumption in the developing world leaves the world’s poorest more exposed to the elements when they do experience detrimental climate events. This makes them effectively more-sensitive to extreme weather.

Consider if you would rather experience a heatwave, heavy downpour, or drought in a developed country with the infrastructure and products to mitigate it or in a less developed country w/o any of these useful systems.

The point of this digression is to say that the costs of mitigation are not just superficial “money”. Instead, they represent real costs to human well-being via reduced availability of goods and services (and the associated reduction in energy consumption).

As I final note, I’ll show another back-of-envelope calculation that indicates that the results of our study are not dependent on obscure or idiosyncratic modeling choices/assumptions, etc.:

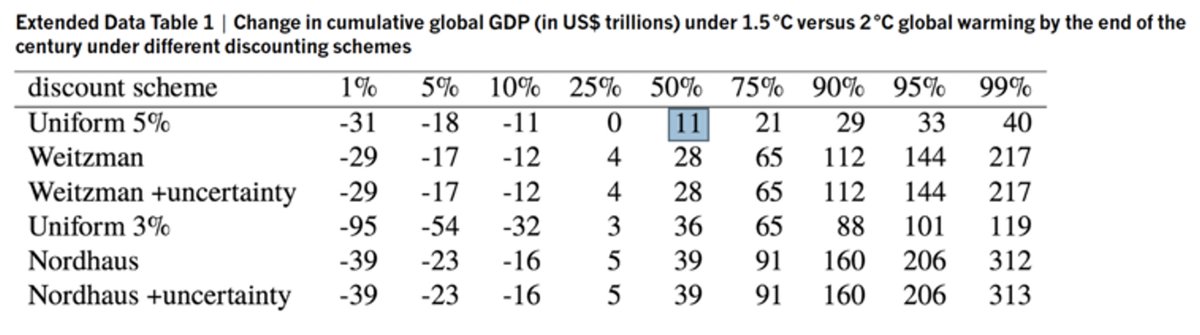

The recent van Vuuren et al. (2020) meta-analysis calculated that limiting global warming to 1.5°C costs $15 trillion more than limiting global warming to 2.0°C (median estimate, through 2100, at a 5%/year discount rate).

nature.com/articles/s4155…

nature.com/articles/s4155…

Burke et al. (2018)’s own median calculation (at the same timeframe and 5% discount rate) shows that limiting global warming to 1.5°C saved $11 trillion more than limiting global warming to 2.0°C.

Again, this shows that mitigation costs associated with achieving the strictest goals are larger than the avoided damages this century.

I am, of course, not advocating for inaction on climate.

It is clear that we must leave a very large portion of available fossil fuels in the ground and virtually all studies in this area imply that we need something akin to a substantial global carbon tax that works to eventually eliminate all greenhouse gas emissions.

But in order to get an accurate sense of the full picture and the tradeoffs at play, we need dispassionate analysis that explicitly includes the costs and not just the benefits of mitigation policies.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh